Colin Thubron - Shadow of the Silk Road

Here you can read online Colin Thubron - Shadow of the Silk Road full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2007, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Shadow of the Silk Road

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2007

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Shadow of the Silk Road: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Shadow of the Silk Road" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Shadow of the Silk Road — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Shadow of the Silk Road" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For Paul Bergne

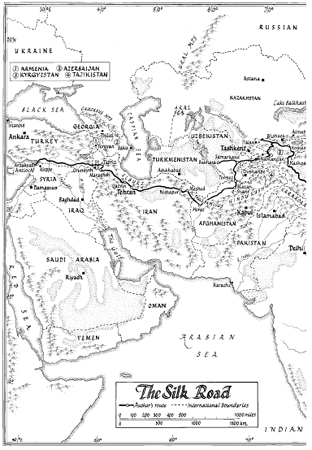

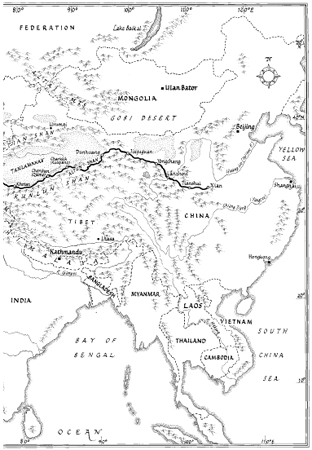

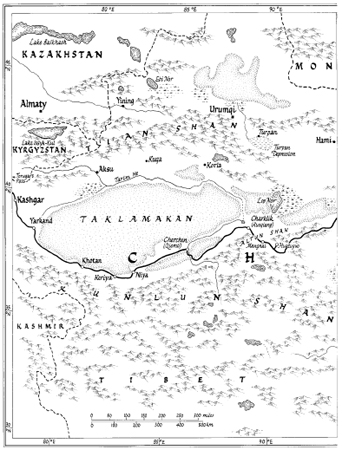

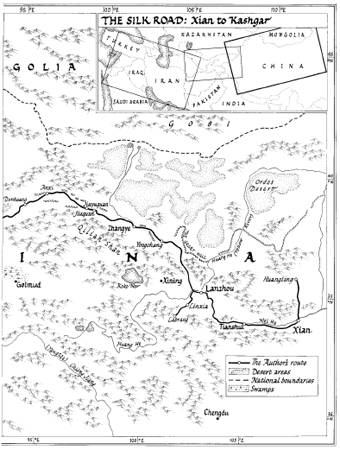

Maps drawn by Reginald Piggott

The journey recorded here was broken by fighting in northern Afghanistan. The section delayed there was travelled the following year, in the same season.

In the midst of political uncertainty, the identities of several people described in the narrative have been disguised.

In the dawn the land is empty. A causeway stretches across the lake on a bridge of silvery granite, and beyond it, pale on its reflection, a temple shines. The light falls pure and still. The noises of the town have faded away, and the silence intensifies the voidthe artificial lake, the temple, the bridgelike the shapes for a ceremony which has been forgotten.

As I climb the triple terrace to the shrine, a dark mountain bulks alongside, dense to the skyline with ancient trees. My feet sound frail on the steps. The new stone and the old trees make a soft confusion in the mind. Somewhere in the forest above me, among the thousand-year-old cypresses, lies the tomb of the Yellow Emperor, the mythic ancestor of the Chinese people.

A few pilgrims are wandering in the temple courtyard, and vendors under yellow awnings are offering yellow roses. It is quiet and thick with shadows. Giant cypresses have invaded the compound and now stand, grey and aged, as if turning to stone. One, it is said, was planted by the Yellow Emperor himself; another is the tree where the great emperor Wudi, founder of the shrine two thousand years ago, hung up his armour before prayer.

The pilgrims are taking photographs of one another. They pose gravely, accruing prestige from the magic of the place. Here their past becomes holy. The only sound is the rustling of the bamboo and the murmuring of the visitors. They pay homage in this temple to their own inheritance, their pride of place in the world. For the Yellow Emperor invented civilisation itself. He brought Chinaand wisdominto being.

The woman is gazing at a boulder indented by two huge footprints. Slight and girlish, she jumps at the sight of a foreigner. Foreigners dont come hereshe laughs through her fingersshe is sorry. The footprints, she says, belong to the Yellow Emperor.

Not really?

Yes. One of his concubines used them to make boots. He invented boots.

We walk for a moment where memorial stones are carved with the tribute of early emperors, and come at the courts end to the Hall of the Founder of Human Civilisation. Its altar is ablaze with candles and incense, and heaped with plastic fruit. The womans gaze, when I question her, stays candid on mine. The Yellow Emperor invented writing, music and mathematics, she says. He discovered silk. This was where history began. People had been coming here generation after generation. And now you too. Are you from your government? But her eyes dip to my worn trousers and dusty trainers. A teacher?

Yes, I lie. Already a new identity is unfurling: a teacher with a taste for history, and a family back home. I want to go unquestioned.

So thats why you speak Mandarin, she says (although it is poor, almost toneless). And where are you going?

I think of saying Turkey, the Mediterranean, but it sounds preposterous. I hear myself answer: Along the Silk Road to the north-west, to Kashgar. And this sounds strange enough. She smiles nervously. She feels she has already reached out too far, and turns silent. But the unvoiced question Why are you going? gathers between her eyes in a faint, perplexed fleur-de-lis. This Why?, in China, is rarely asked. It is too intrusive, too internal. We walk in silence.

Sometimes a journey arises out of hope and instinct, the heady conviction, as your finger travels along the map: Yes, here and hereand here. These are the nerve-ends of the world

A hundred reasons clamour for your going. You go to touch on human identities, to people an empty map. You have a notion that this is the worlds heart. You go to encounter the protean shapes of faith. You go because you are still young and crave excitement, the crunch of your boots in the dust; you go because you are old and need to understand something before its too late. You go to see what will happen.

Yet to follow the Silk Road is to follow a ghost. It flows through the heart of Asia, but it has officially vanished, leaving behind it the pattern of its restlessness: counterfeit borders, unmapped peoples. The road forks and wanders wherever you are. It is not a single way, but many: a web of choices. Mine stretches more than seven thousand miles, and is occasionally dangerous.

But in the temple of the Yellow Emperor, the womans gaze has drifted north. He was buried up there on the mountain, she says. Its written that people tugged at the emperors clothes as he flew to heaven, trying to pull him back. Some say that only his clothes are buried there. But I dont think this is true. She speaks softly, with a tinge of unexplained sadness. The grave is quite small, not like those of later emperors. I think life was simpler in those days.

We walk for a minute longer under the eaves of the temple. Then, suddenly, the quiet is shattered by the stutter of power-drills and the groan of dump-trucks.

Theyre building the new temple, she says. For celebrations and conferences. This ones too small. The new one will hold five thousand people.

Later I peer down from the hillside on the building site where it will be. I imagine the stressless, unchanging temple-pavilions of China rising from their wan granite. This place, Huangling, is only a hundred miles north of modern Xian, but is lost deep in another time of erosion and poverty. Who will come?

But the whole site is resurrecting as a national shrine, and already the older temple is filled with the memorial stelae of Chinas statesmen offering homage to the father of the nation. Here is the stone calligraphy of Sun Yatsen from 1912, and of Chiang Kai-shek, predictably coarse; of Mao Zedong, who was later to condemn the Yellow Emperor as feudal; of Deng Xiaoping and the hated Li Peng.

The clamour of restoration dies as you climb the track where it snakes through the cypress woods. From somewhere sounds the drilling of a woodpecker, and human voices echo and fade above you. Here and there a yellow flag on a bamboo pole marks the way. You are sinking back in time. Close to the summit the path becomes a stone stairway, and the trees turn phantasmal, their trunks twisted like sticks of barley-sugar or wrenched open on swirling slate-blue veins. Here the grandest mandarin, even the emperor, abandoned his sedan chair and approached the mausoleum on foot.

For there is little in the endfrom music to the calendarwhose discovery is not attributed to the Yellow Emperor. He reigned for a hundred years until 2597 BC before ascending to heaven on a dragon. It was he who instituted the festivals of earth and silk. After him the reigning emperors, from a remote time, inaugurated the year by ploughing a ritual furrow, while their empresses offered cocoons and mulberry leaves at the altar of his wife Lei-tzu, the Lady of the Silk Worms.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Shadow of the Silk Road»

Look at similar books to Shadow of the Silk Road. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Shadow of the Silk Road and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.