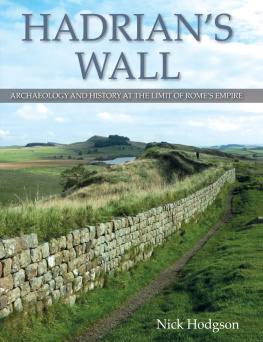

HADRIANS

WALL

ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY AT THE LIMIT OF ROMES EMPIRE

HADRIANS

WALL

ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY AT THE LIMIT OF ROMES EMPIRE

Nick Hodgson

ROBERT HALE

First published in 2017 by

Robert Hale, an imprint of

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2017

Nick Hodgson 2017

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 71982 159 2

The right of Nick Hodgson to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Contents

Preface

T HIS IS NOT A GUIDE BOOK TO THE REMAINS of Hadrians Wall, but (I hope) a simple explanation of how it came to be built, the major events in its history, what purpose it was intended to serve, what life was like for the people who lived on the Wall and in its shadow, how archaeologists know these things, and the limits to what they can know.

One of the curious things about Hadrians Wall is that, although they all rely on the same evidence for what happened in the past, archaeologists approach it from different perspectives. There is much disagreement between experts, and not a little misunderstanding. I hope that by producing a straightforward and up-to-date account of the Wall, based on modern archaeological and historical research, I can show readers that there is more than one way of interpreting the Wall, but at the same time offer a factually reliable and interesting account for visitors, general readers, students and archaeologists.

This version of the Wall story gives more emphasis than most to the indigenous population of Britain and the way the Wall affected them, something we have only recently begun to learn more about. It also reflects my concern that archaeologists are getting less and less confident about trying to draw general historical conclusions from the evidence. Historical narrative is increasingly out, and the social history of what people wore and ate, increasingly in: but I try to show that there is room for both, and that we can begin to obtain a clearer picture of how the experience for those who lived with the Wall changed from one century to another.

This book may seem unusual because I have deliberately not named any modern archaeologist or historian in the text (with rare exceptions). This is to make for accessibility and readability, and to avoid getting bogged down in debates between personalities. It is also because I feel that sometimes we can only look at a problem afresh by stepping away from it, looking at it from a different angle, and forgetting for a moment the accretion of thought around it. This means I inevitably describe ideas and arguments without crediting their authors in the text, but I have tried always to acknowledge them in the endnotes. I apologise if I have inadvertently failed to do this at any point.

I thank all colleagues who have supplied information or discussed the problems of Hadrians Wall over the years. They are too many to name individually, but I am particularly grateful to David Breeze for his friendly encouragement, and for agreeing to read and comment on the text. Paul Bidwell has also read the text and offered valuable suggestions. James Bruhn has provided invaluable discussion and practical assistance. None of these is responsible for any errors in the book, or necessarily agrees with any of the views advanced.

I must thank three people to whom I feel especially indebted. The late Cliff Davies, an inspiring tutor who was unflagging in his help to me as an undergraduate, can never have dreamt that his training in the use of modern historical evidence would one day be applied to Roman times. The late Charles Daniels, my PhD supervisor, first encouraged my move into archaeology and placed his wide knowledge of the Roman frontiers at my disposal. Above all, I have been privileged to work for nearly thirty years with Paul Bidwell, at once a teacher and a friend, and to benefit from his generosity and extraordinary insights. Many of the ideas in this book are his, and I offer it to him in gratitude.

Newcastle upon Tyne

2016

Introduction

WHAT IS HADRIANS WALL?

M OST PEOPLE HAVE HEARD OF THE GREAT wall built by the Roman Emperor Hadrian in northern Britain. It has been a World Heritage Site since 1987, and year by year is more aggressively marketed to tourists. Of the hundreds of thousands who make the pilgrimage to see it, many are thrilled by the sight of Hadrians Wall in the wildest of Northumbrian settings. The Elizabethan antiquary William Camden (one of the first to give an archaeological description of the Wall, in 1599) was similarly moved: Verily I have seen the tract of it over the high pitches and steep descents of hills, wonderfully rising and falling. Many of the modern visitors to the best known parts of the Wall rise above the relentless retail opportunity of the soulless souvenir shops and the corporately branded information panels, and when they get amongst the lichen-covered Roman stones feel an unmistakable feeling that they stand among the abandoned ruins of a vanished civilization. The questions are soon triggered: who exactly were these Romans? Why did they come to this remote island and raise such massive structures here? And where did they go? Why was this most impressive and enduring phase in the archaeological record of northern Britain abandoned, leaving traces of a Mediterranean-based culture, still visible in the remote countryside of Northumberland and Cumbria after 1,600 years?

Fig. I.1 Verily I have seen the tract of it over the high pitches and steep descents of hills, wonderfully rising and falling: the Wall as it appears today, west of Housesteads.

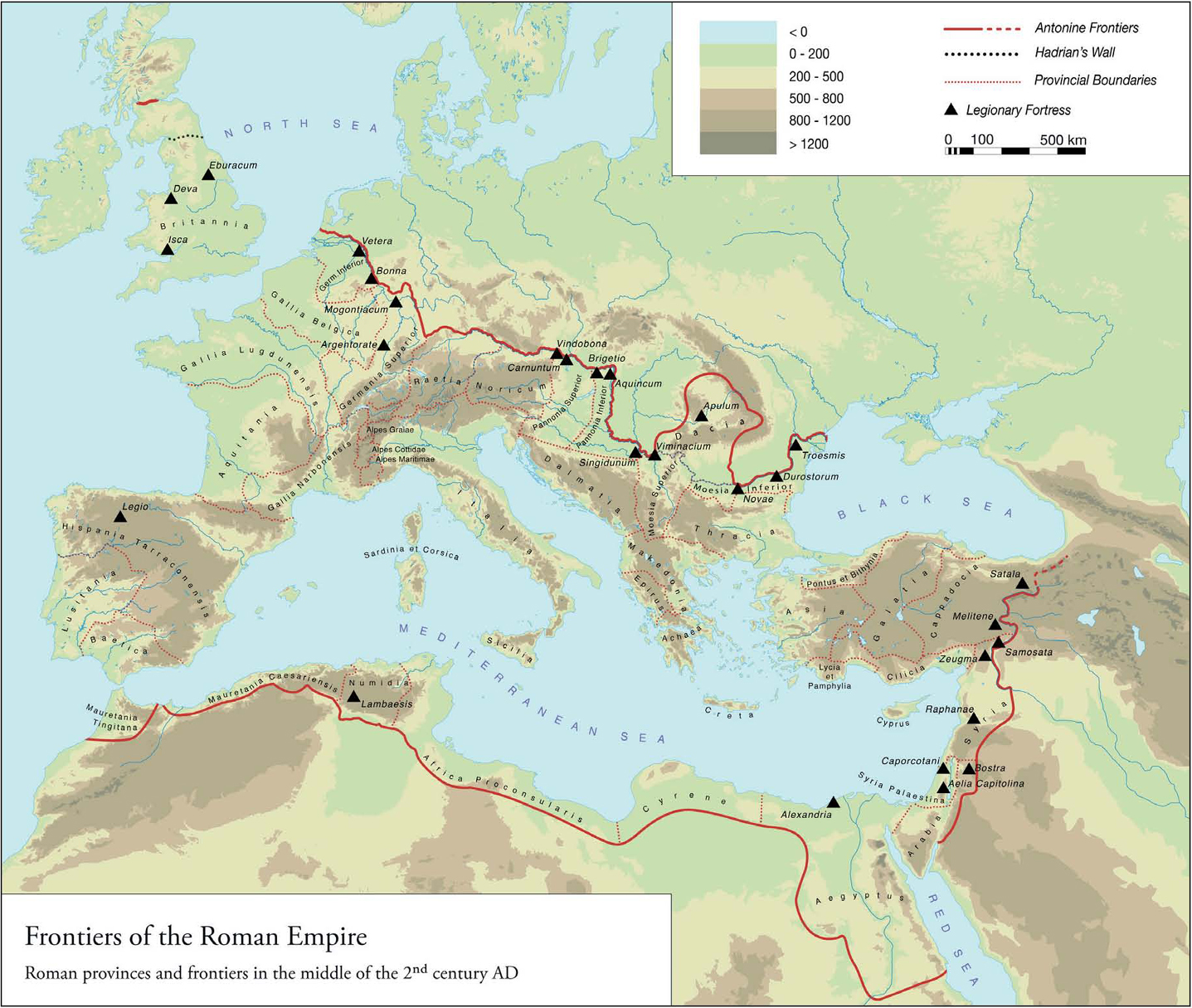

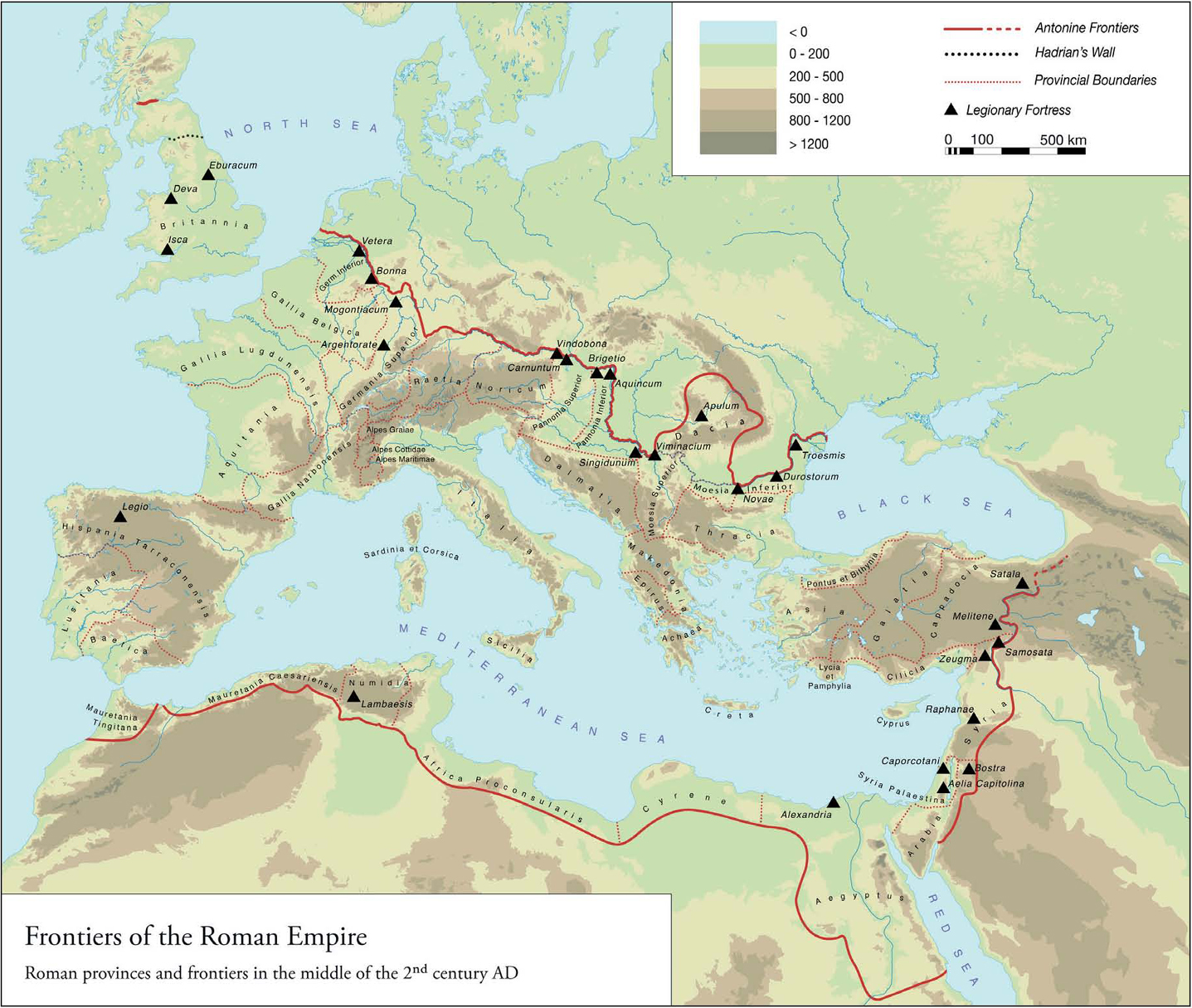

Fig. I.2 Hadrians Wall did not stand alone as a fortification line at the edge of the Roman Empire: this map shows the frontiers of the Roman Empire in the second century AD. FRONTIERS OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE CULTURE 2000 PROJECT/D. J. BREEZE

A smaller number of enthusiasts are rapidly hooked and begin to wonder what archaeological secrets are held in the parts of the Wall that now lie wholly buried, whether under sheep-cropped grass or beneath the urban landscapes of Tyneside or Carlisle. This book sets out to answer those questions, and to explain what modern archaeology tells us about the reality of events and life on Hadrians Wall over the three centuries of its operation.

It is important at the outset to see Hadrians Wall in its context: the Wall did not stand alone as a fortification line at the edge of the Roman Empire. Not many visitors to Hadrians Wall know that only 160km (100 miles) north there was an equally elaborate Roman frontier work, the Antonine Wall in Scotland. This was built only twenty years after work had begun on the much better known wall of Hadrian, and superseded Hadrians barrier for a brief twenty-year period. Fewer still appreciate that the remains of another great series of Roman barriers can be traced for nearly 500km (300 miles) through modern Germany, along the land frontier of the empire from near Koblenz on the Rhine to the area of Regensburg on the Danube.

Next page