Also by John Man

Gobi

Atlas of the Year 1000

Alpha Beta

The Gutenberg Revolution

Genghis Khan

Attila

Kublai Khan

The Terracotta Army

The Great Wall

The Leadership Secrets of Genghis Khan

Xanadu

Samurai

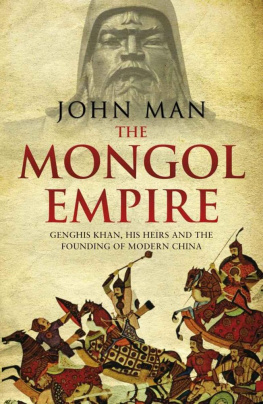

The Mongol Empire

Saladin

Amazons

BARBARIANS AT THE WALL

The First Nomadic Empire and the Making of China

JOHN MAN

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

6163 Uxbridge Road, London W5 5SA

penguin.co.uk

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Bantam Press

an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright John Man 2019

Cover photograph Getty Images/DeAgostini

Cover design by Rhys Willson/TW

John Man has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781473554191

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

For Ge Jian, with thanks

Introduction

A NEW BROOM SWEEPS THE CHINESE SKIES

In the spring of 240 BC , astronomers employed by the nineteen-year-old King Zheng of Qin, deep in the heartland of modern China, reported the appearance of a comet. It was in fact the comet now named after Edmond Halley, the British astronomer who in the early eighteenth century discovered that it returned every seventy-six years. To Zhengs astronomers this comet, like all comets, was a heaven-sent omen of change possibly good, possibly disastrous. Comets were commonly called broom stars, because, wrote a sixth-century Chinese historian, the tail resembles a broom Brooms govern the sweeping away of old things and the assimilation of new ones.

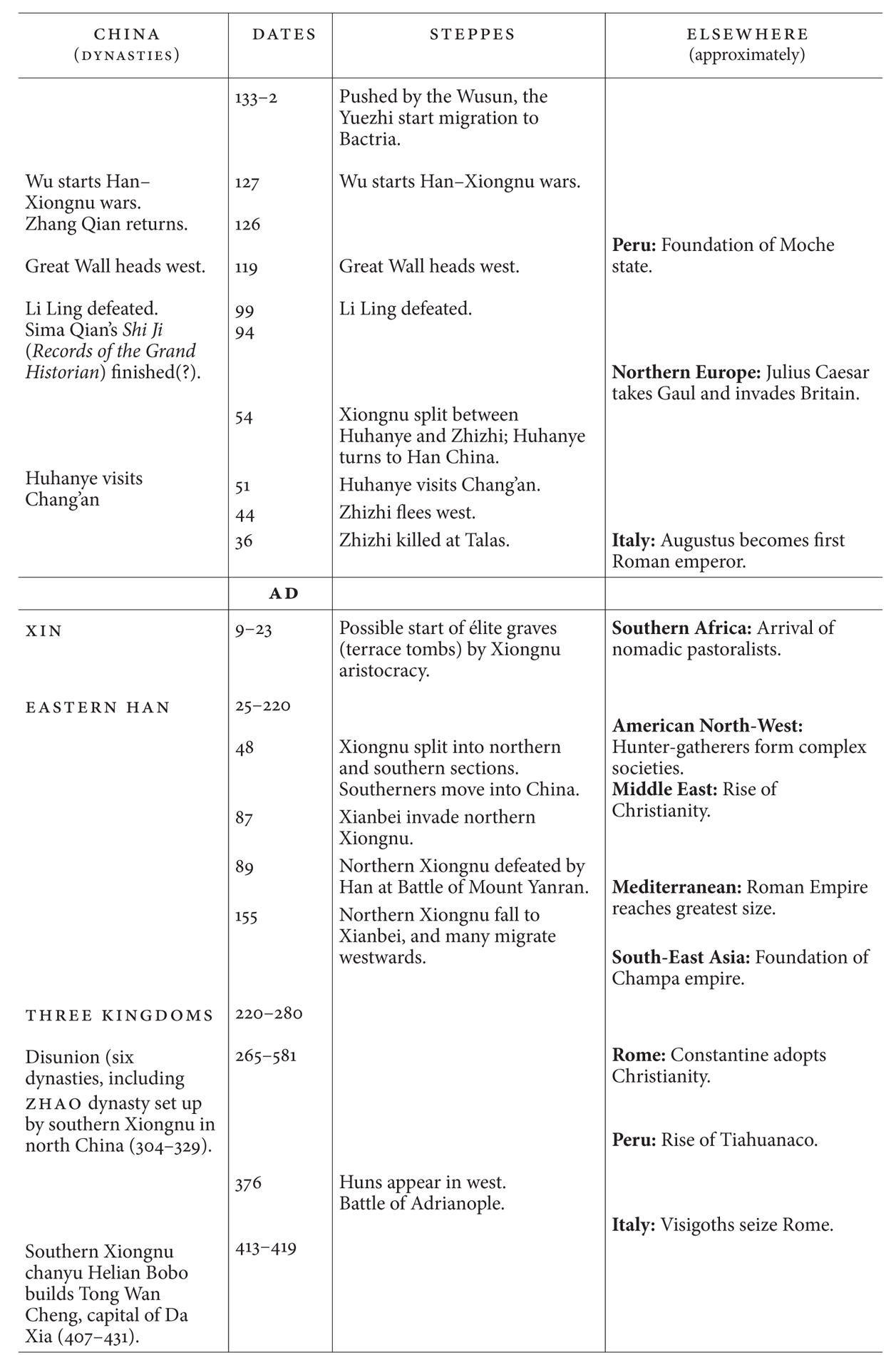

As in the heavens above, so in the earth below: King Zheng, ruling with the Mandate of Heaven, was already something of a comet himself, the newest of brooms. In the course of five centuries of incessant warfare, states, mini-states and city-states had whittled themselves down to seven. Among them, Qin (pronounced Chin) was the hardest of the hard, with an army honed for conquest. Being the first among equals was not enough for Zheng. He wanted to be the one-and-only ruler. It took nine years of war. In 221 BC , Qin emerged as the core of todays China, with Zheng as its First Emperor, ruling in this world and (he assumed) the next, as tourists by the million can see when they admire his spirit warriors, the Terracotta Army.

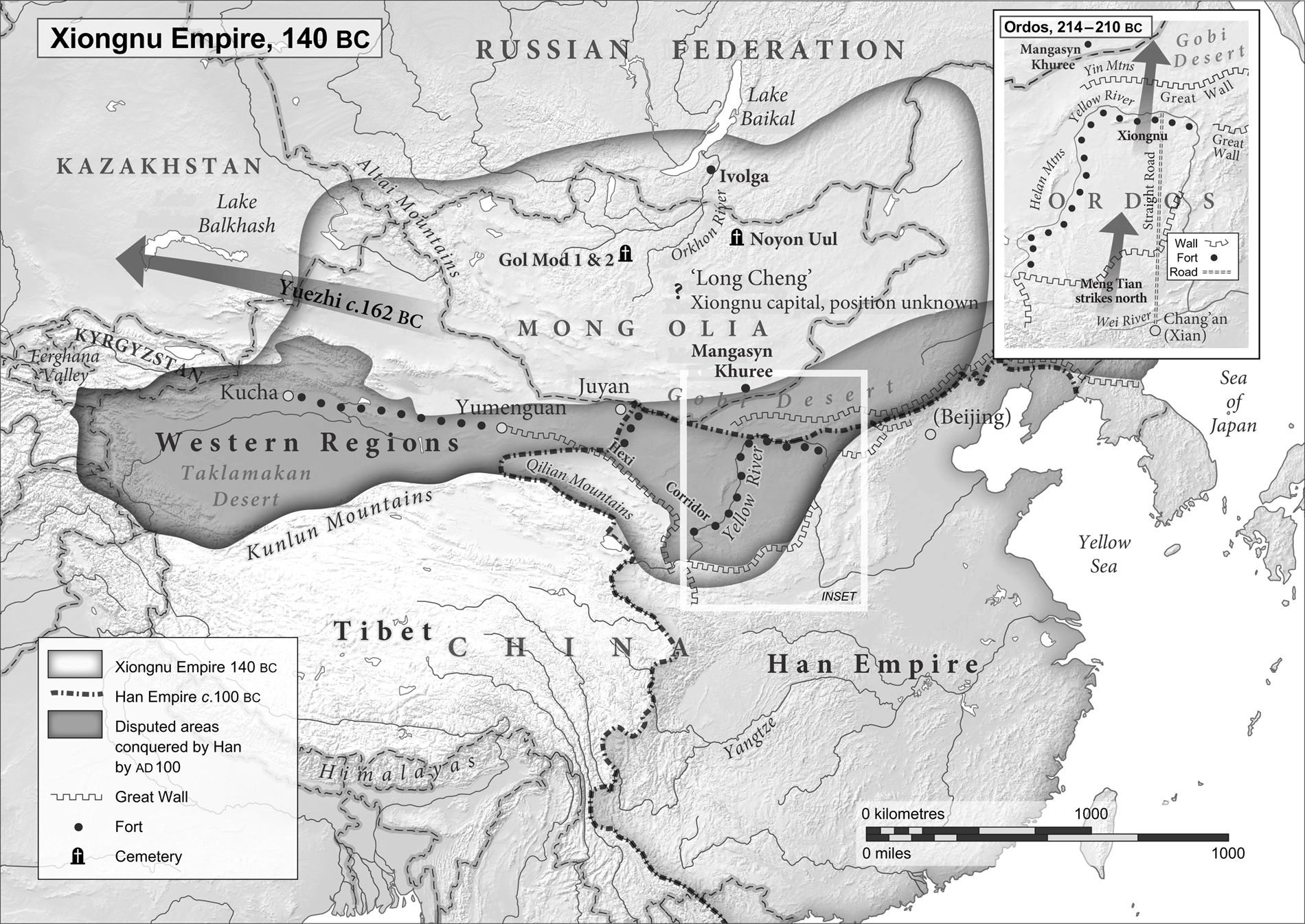

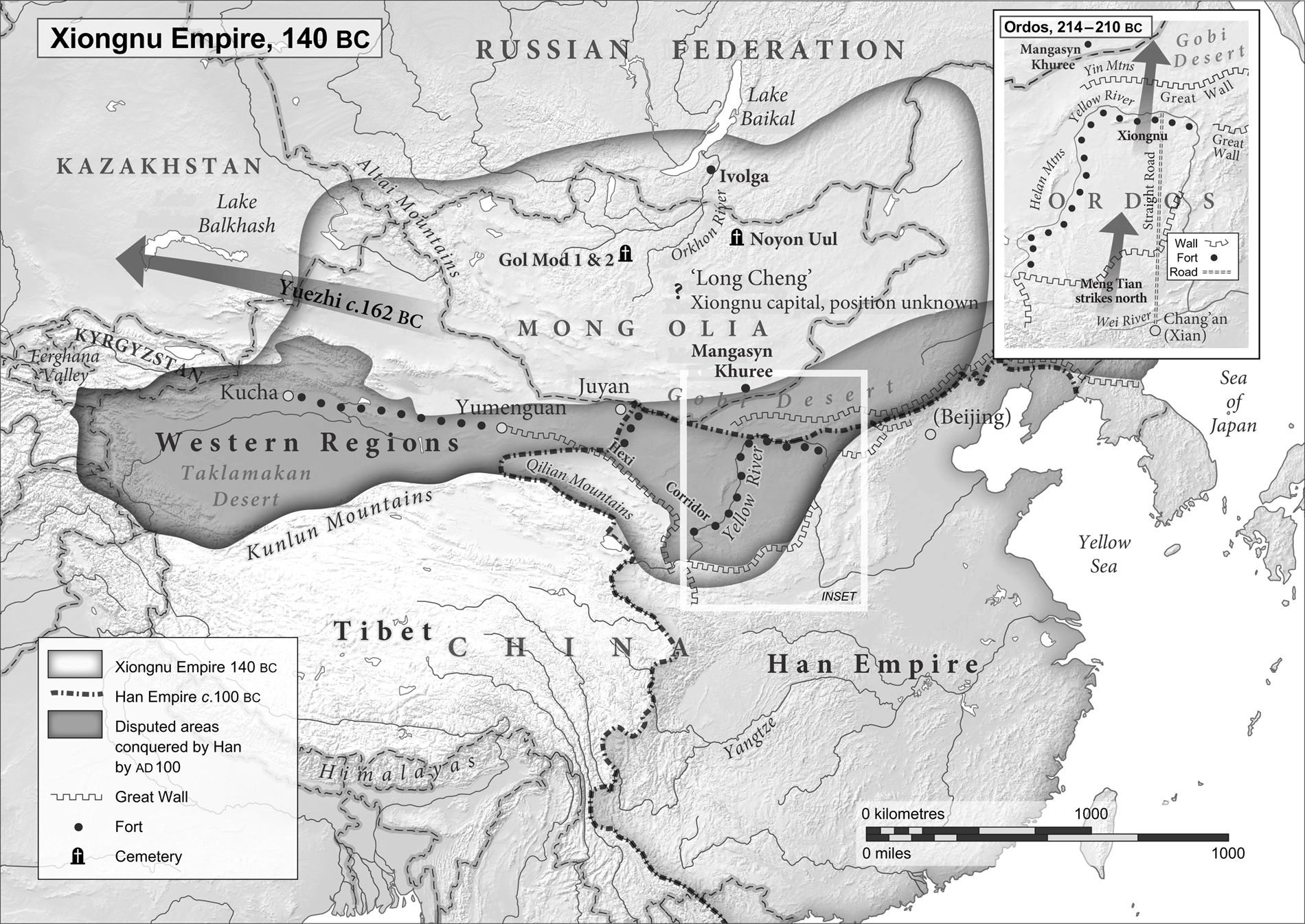

But the Great Comet of nineteen years earlier foreshadowed more than just change. Disaster also loomed, from beyond the borders of Zhengs new empire. To the north, in the vast grasslands and semi-deserts of Inner Asia, were tribes with a very different lifestyle: no cities, no farms, an endless supply of horses, and fearsome skills with bows and arrows. For centuries, they had been little more than gangs, making pinprick raids on the Chinese heartland. But now they suddenly became a real danger.

Though famous in China and Mongolia, few westerners know about this people. To Mongolians, they are Hunnu or simply Huns. The Chinese for Hun is Xiongnu, pronounced Shiung-noo. Because Chinese written sources dominate the history of this relationship, thats how they are generally known today, though mainly to specialists.

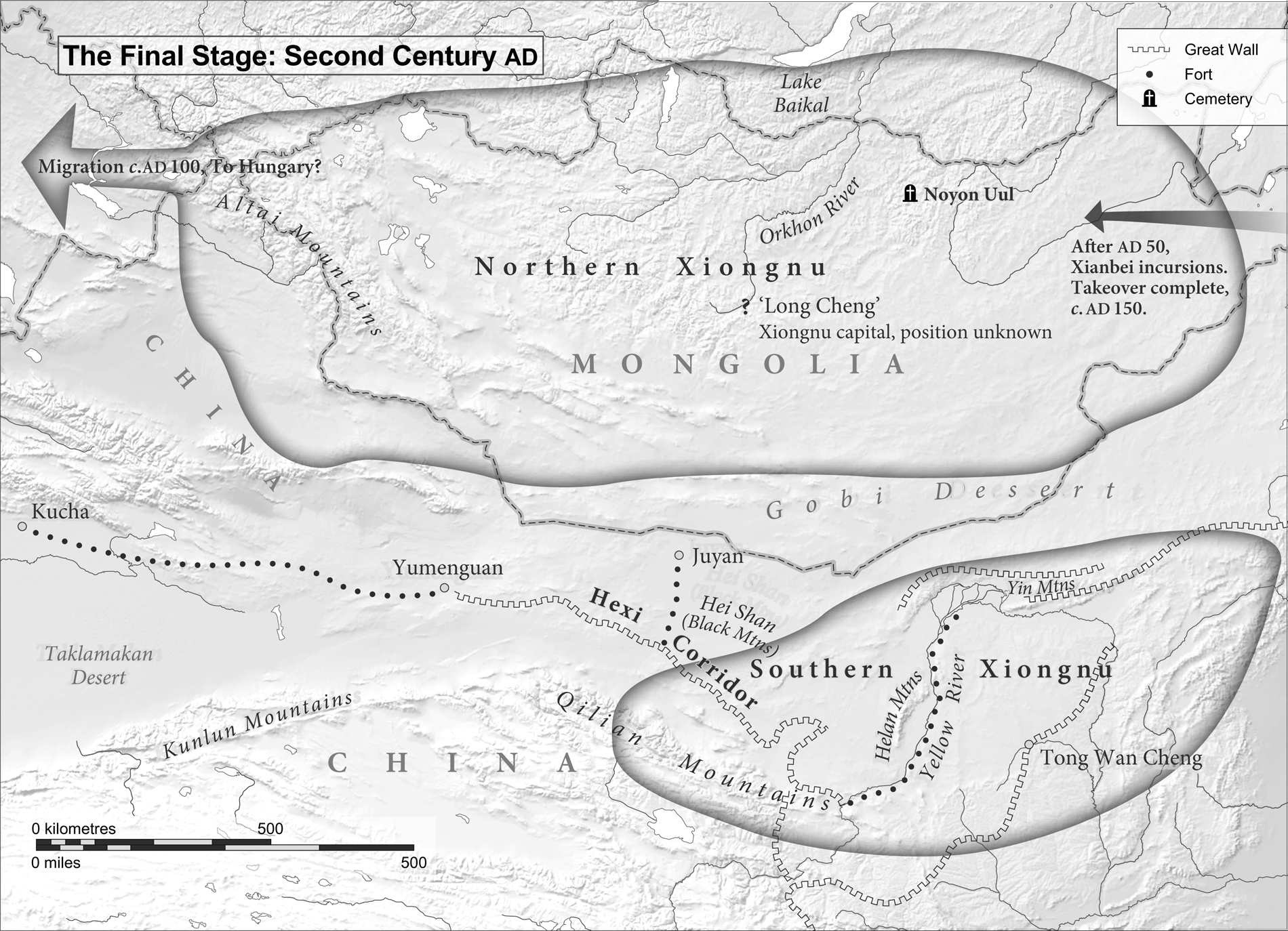

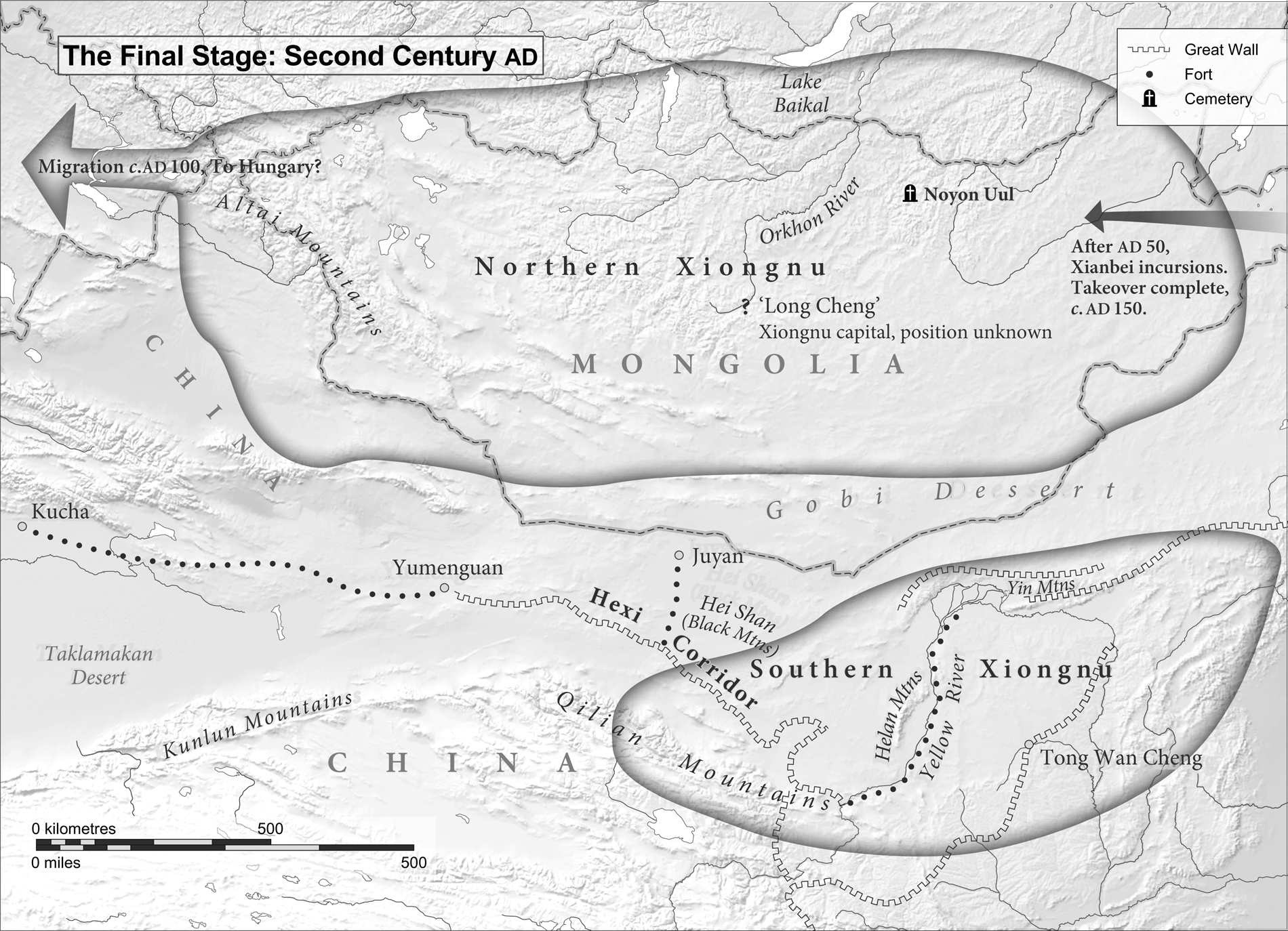

They deserve better. They lacked many elements that are in theory essential to statehood, yet they forged the first nomadic empire the third greatest land empire in history before the rise of modern super-states (the first and second being the Mongol empire and the medieval Muslim empire). They are the reason China reaches so far westward. They inspired one of the worlds best-known monuments, the Great Wall. They were remarkably successful, lasting some three hundred years, making them the most enduring of the many successive nomadic empires. And they are possibly the ancestors of the tribe that under Attila helped destroy the Roman empire in the fifth century AD.

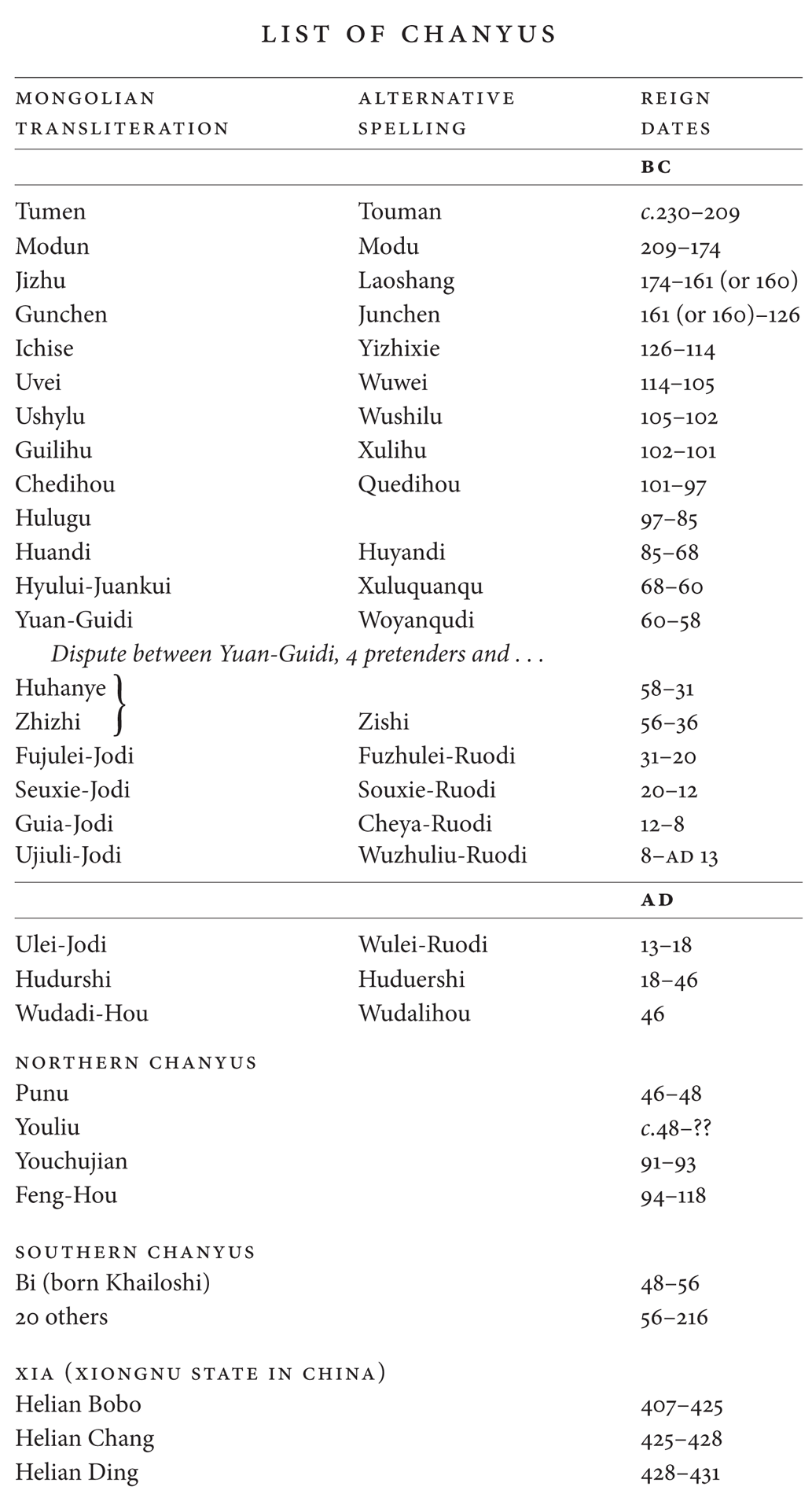

Finally, their emergence is evidence that opposition in this case from China inspires divided peoples to unify. Until recently, the explanation for the rise of the Xiongnu was based on Chinese xenophobia that the nomads were dreadful people, the antithesis of everything civilized; that the violence was all on their side; and that China, the fount of civilization in Asia, was the innocent victim of their predatory habits. Today, many academics claim the opposite. They argue that the rise of the Xiongnu backs a great historical truth, an equivalent of Newtons Third Law: For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. Let world historians argue about how generally true this may or may not be, but it seems to explain what happened around 200 BC , when Chinese force begot a counter-force on the grasslands of Inner Asia. Or, in human terms, a powerful charismatic leader on one side inspired a leader of similar qualities on the other. In this view, it was the First Emperor, Chinas unifier, who started the confrontation. His empire-building acted like a hammer on heated iron fragments, forging the nomads together for the first time. For over three centuries, the two remained in a precarious and violent balance, despite the vast 40:1 difference in population, until China proved there was no law after all, by using overwhelming force to shatter and scatter the Xiongnu.

But their way of life remained. Over the next 2,000 years, it underpinned another seventeen nomadic and semi-nomadic polities chiefdoms, super-chiefdoms, kingdoms, empires with an average duration of 157 years. The greatest was the Mongol empire (12061368), which at its height ruled all China and most of Inner Asia. Its founder, Genghis Khan, saw himself as the heir to a tradition of imperial nomadism reaching back over a thousand years to the Xiongnu. Mongolians today claim them as ancestors, with both cultural and genetic links.

Next page