There in the vast steppe, flooded with sunlight, he could see the black tents of the nomads, like dots in the distance. There was freedom there time itself seemed to stand still as though the age of Abraham and his flocks had not passed

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Crime and Punishment

It is vain to dream of a wilderness distant from ourselves. There is no such. It is the bog in our brains and bowels, the primitive vigour of Nature in us, that inspire that dream.

Henry David Thoreau

When I was a child my grandmother used to call me a Mongolian. In memory the word evokes the scent of grass and of fallen leaves, some atmosphere of twilight and of horses.

My grandmother lived at the top of an Irish village with views southwards to the Mountains of Mourne. In the evenings, in the long dusk that my grandmother called daylegone, I played on a raised pavement that ran along the churchyard wall, beneath an arch of lime trees. They were solitary and elaborate adventures involving horses and culprits. My stallion pranced through swathes of freshly mown grass and piles of autumn leaves. We leapt the wall in a single bound.

When it grew dark my grandmother would call me home, her voice looping in the lingering twilight like a rope. I resisted as long as I could, galloping between the trees in the thickening gloom, against the tug of her voice. When she stopped calling I sat in thrones of leaves gazing to the south where the Mountains of Mourne shouldered the horizon. The mountains were dark and mesmerizing, the frontier to the wide world of County Down. My father said that beyond the mountains lay the sea.

When the long lasso of my grandmothers voice came again my horse was already melting away between the graves. I turned home, and presented myself in the back hall with skinned knees and leaves in my hair. As my grandmother bent over me to brush and straighten my clothes, she always said the same thing. Like a Mongolian, she sighed. Just like a little Mongolian.

I never heard anyone else speak of the mysterious Mongolians, and I had no idea who they were. I recognized the word was an admonition of sorts but I sensed it also contained a note of praise. I liked its unruliness and its ambiguities, and I wanted to live up to the idea of recklessness that it seemed to imply.

Long before I had any clear sense of Mongolia as a place, the word belonged to those intense adventures played out each evening in the slow descent of an Irish twilight, as I tugged against the mooring of my grandmothers voice calling me home.

It was in Iran, twenty-five years ago, that I first saw nomads. I was part of an expedition looking for the Persian Royal Road. Led by a charming charlatan who was a cross between Rommel and W.C. Fields, our small and happily deluded team spent eighteen months in the field, rattling around Anatolia and the Zagros mountains with a couple of Land Rovers, a leaky tent and a copy of Herodotus. It was the best of journeys. The landscapes were magnificent, the people hospitable and we had the alibi of historical purpose.

In the Marv Dasht plain beneath the ruins of Persepolis the Qashgai tribes were trooping north to their summer pastures in the mountain valleys around Hanalishah. Skirting fields of new wheat, they passed like a medieval caravan, a whole society set in motion, moving northward to new grass. The layered skirts of the women flashed with gold and silver thread as they ran after straying lambs. Riding slim, leggy horses, the men trotted back and forth along the perimeter of the caravan shouting to one another in a language that had come with them from Central Asia. Camels bearing tent poles and rolled carpets and wide-eyed children swayed through veils of dust. On the edge of the village of Sivand, an old man hoeing vegetables in a walled garden straightened to watch them pass, his face darkening with an ancient antipathy.

I had never seen such glamorous people. They owned not a square inch of land but they strode across the province of Fars towards the mountain passes as if it were their private estate. Passing beneath the stone palaces of Persepolis, they were oblivious to their allure.

Some weeks later we penetrated the mountains around Ardekan where Alexander had defeated the last Achaemenian defences at the Persian Gates on his way to the prize of Persepolis. In these narrow valleys we paid a visit to a Qashgai chief. It was June, the best month, when the grass was rich and the flocks were fat.

Nomad tents have big doors, the khan said as we arrived, referring to Qashgai hospitality. We sat inside enthroned on splendid kilims and bolsters, looking down over a stony slope where his son was herding goats towards the green line of a river. Piled along the rear wall of the tent were embroidered sacks and chests and saddle-bags, the furniture of nomads. The khans daughters left their looms at the other end of the tent to bring us glasses of tea and water pipes.

We talked of politics, and the government pressure on the tribes to settle.

It was always thus, the khan said. The people of the towns, the peoples of the fields, worry they cannot control us. They think of us as barbarians. He smiled, sensitive to the irony of this, a gracious host with elegant manners, a man whose tribal pedigree went back three centuries. They want us to settle in one place. They want to make us part of the life of the towns.

The canvas walls filled with wind and the tent creaked like a ship. On the tent poles the saddle-bags swayed.

The tribes were powerful once in Iran. But those days are gone. I do not know what the future holds for nomads. But I fear that we are seeing the end of a way of life. He gestured to the valley as if the landscape itself was in retreat. We have migrated through these mountains for centuries. We came to these lands in the train of Genghis Khan.

The Qashgai are a remnant of one of the innumerable nomadic peoples who emigrated from the great grasslands of Central Asia. Iran was a civilization prone to exhaustion and Persian history was shaped by these nomadic incursions. When dynasties weakened, when art became decadent, when the officials grew corrupt and the aristocrats soft and cowardly, they knew the barbarians would soon be coming, a scourge and a salvation.

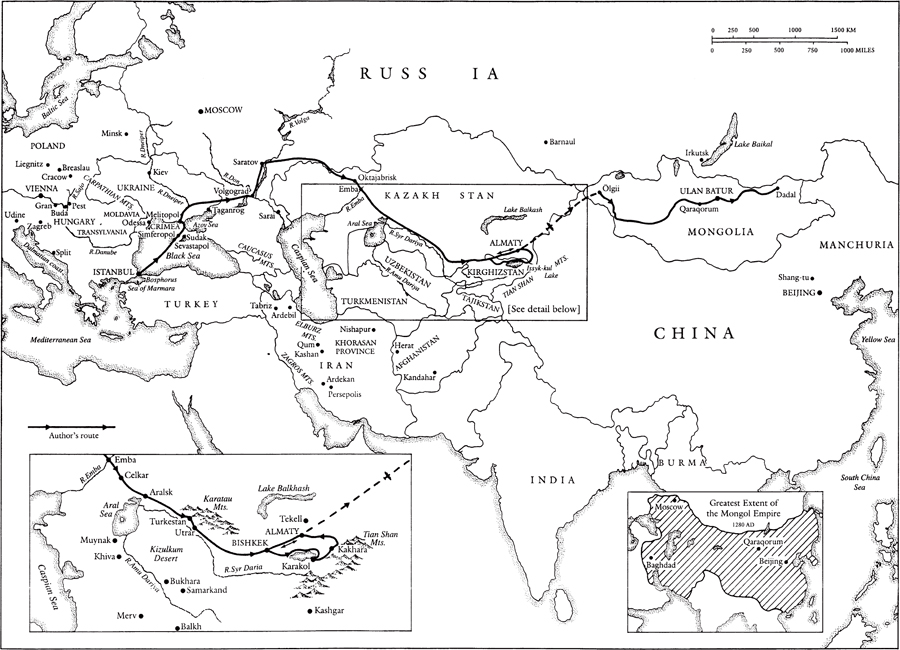

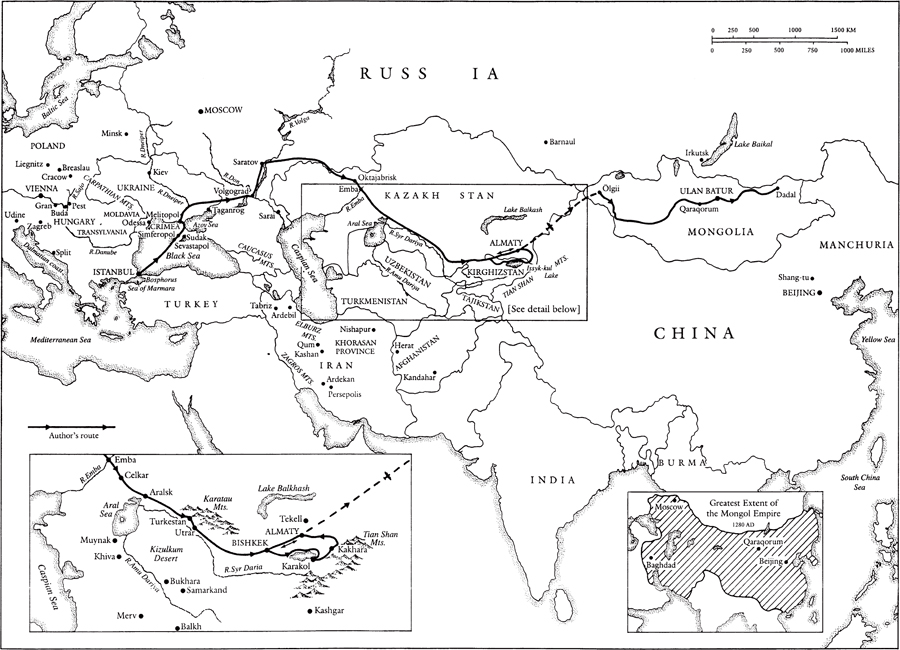

This pattern of untamed horsemen, bursting forth from the steppes to prey on their more suburban neighbours, was repeated throughout Asia. They came with a bewildering variety of names: the Cimmerians, the Sarmatians, the Tocharians, the Xiongnu, known in Europe as the Huns. Russia was not free of the Tartar yoke until the sixteenth century. In India the great Mughal Empire was founded by a nomadic barbarian from beyond the Oxus. In China, they built the Great Wall in the vain hope that they could keep the nomads at bay.

The high-water mark of nomadic power were the Mongols of the thirteenth century. In the course of a single generation, under the charismatic leadership of Genghis Khan, they rode out of the steppes of Central Asia to forge the largest land empire the world has ever seen. From the South China Seas to the Baltic they stepped from the nightmares of townsfolk onto their doorsteps. Suddenly the Mongols seemed to be everywhere at once, threatening to gatecrash Viennese balls, carrying off princesses in Persia, over-throwing Chinese dynasties, sacking Burmese temples, putting Budapest to the torch, launching seaborne invasions of Japan. Even in a distant England they were front-page news. Matthew Paris, the thirteenth-century chronicler, sounded the last trumpet: the Mongols were coming and the End was nigh. Hysterical congregations crowded into their parish churches to pray for deliverance.