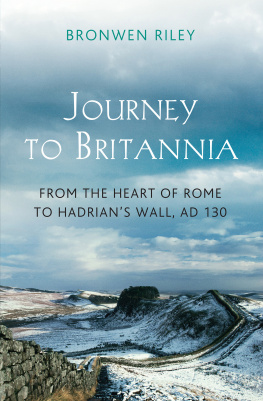

THE EDGE OF THE EMPIRE

Pegasus Books LLC

80 Broad Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10004

Copyright 2015 by Bronwen Riley

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition May 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without

written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in

connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part

of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or

by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other,

without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-129-8

ISBN: 978-1-68177-177-9 (e-book)

Distributed by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

PATRI QUI PRIMUS MIHI MONSTRAVIT

VESTIGIA ROMANORUM MATRIQUE

QUAE VIAM PATEFECIT

Contents

____

____

POSTSCRIPT

Beyond AD 130: People, Politics and Places

____

____

*

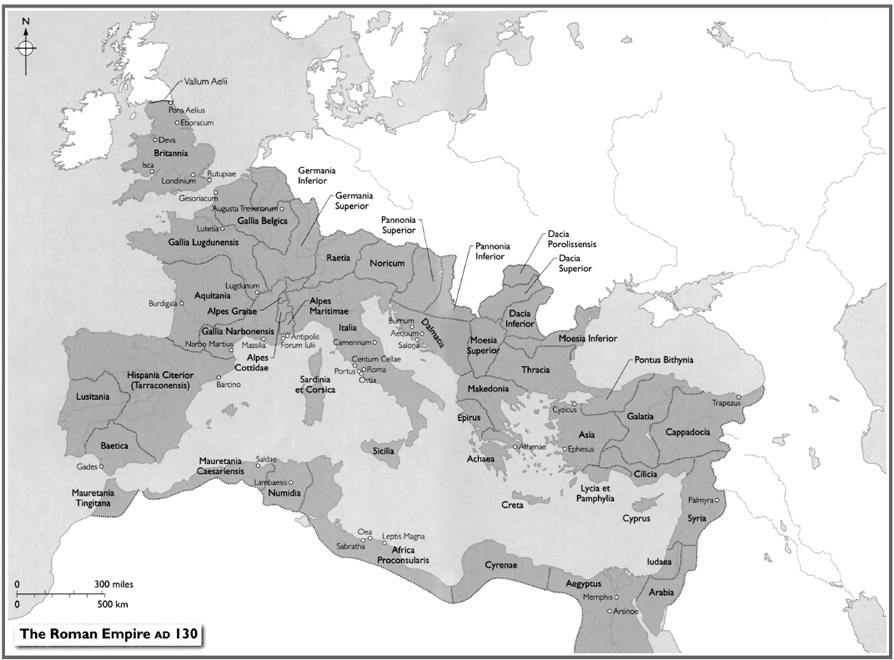

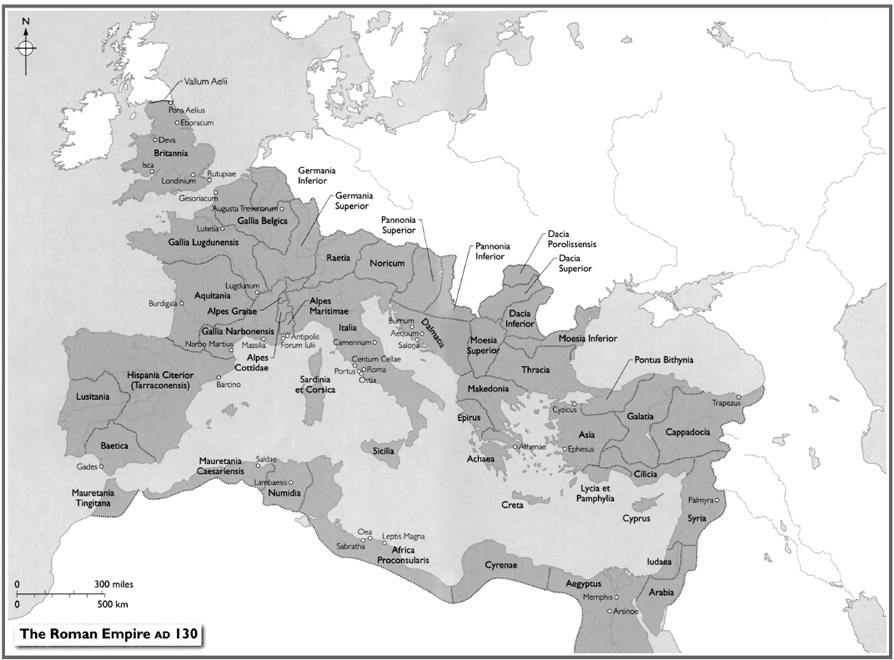

BOWNESS-ON-SOLWAY in Cumbria was the north-westernmost limit of Hadrians Wall. In AD 130 it was alsoapart from a handful of outposts north of the Wallthe most north-westerly point of the entire Roman Empire. From here, according to my online route planner, it is a distance of 1486.9 miles (2392.9km) to the Capitoline Hill (Piazza del Campidoglio) in Rome. The itinerary tells me that were I to travel by car, the journey would take 22 hours and 8 minutes.

The suggested route is not, of course, the only way of getting there, simply the most direct, along the fastest roads. Such a concept would have been familiar to the Romans, who used itineraries based on similar principles: routes drawn as a series of straight lines, giving distances between suggested stopping points, with symbols denoting towns, ports, temples and various types of accommodation available along the way.

Motorways now bypass the towns and cities through which the Romans once travelled and the stopping places where they would have sought refreshment for themselves and their horses. Scanning the modern route through England, I look for the Roman towns, forts and settlements that I might pass on my journey and find them straight away. Soon after leaving Bowness-on-Solway (Maia), I would pass by Carlisle (Luguvalium), a Roman military base and later Romano-British town. A little further south in Lancashire, having sped by Lancaster, I would cross the River Ribble, just a few miles west of Ribchester. Both these places were Roman forts, indicated by the -caster and -Chester in their modern names: from the Latin castrum, via Old English ccester, by which the Anglo-Saxons denoted a place of Roman origin. What the Romans called Lancaster is unknown, but Ribchester went by the splendid name Bremetenacum Veteranorum. This comes from the Celtic for a roaring river, Bremetona (an apt name, as the Ribble has devoured a third of the fort), and the Latin for of the veterans, indicating that soldiersat one time Sarmatian cavalry originally from the Ukraine and southern Russiahad settled here on retirement.

Just off the M6 Toll Road in Staffordshire is Wall (Letocetum), which provided a well-appointed government rest house or mansio for official travellers on Watling Street, a key military road between the south coast and North Wales. Once on the Mi, I would pass by St Albans (Verulamium), a town that came to prominence soon after the conquest thanks to its strategic position north of London on Watling Street and its pro-Roman inhabitants. The rather less amenable Queen of the Iceni, Boudicca, torched the place in AD 61. She did the same to London (Londinium), massacring its citizens and burning the future provincial capital so effectively that it left forever a glaring red scar of burnt clay in the earth, which archaeologists refer to as the Boudiccan destruction layer.

The twenty-first-century route now bypasses London on the M25 and joins the M20 at Dartford, following a much more circuitous way to the coast and the Channel Tunnel south of Dover than the old Roman road. By contrast, Watling Street runs south of London in a no-nonsense line, directly connecting the capital with the ports of Dover (Dubris) and Richborough (Rutupiae) via Canterbury (Durovernum Cantiacorum).

The way in which Romes tentacles reached even the most out-of-the-way places, in what for the Romans was our really faraway island, never ceases to amaze me, as does the origin of the men and women who ended up here from all corners of the empire. Just down the coast from Bowness-on-Solway, at the fort of Maryport (Alauna) on the Cumbrian coast, Caius Caballius Priscus, born in Verona, was a tribune here between AD 128 and AD 131. Marcus Censorius Cornelianus, from Nmes in the south of France, served here in AD 132 before being sent to Judaea. Lucius Cammius Maximus, prefect of the camp between AD 133 and AD 135, came from Austria, returning to the region to serve on the Danube. And at some point in the second or third century, Gaius Cornelius Peregrinus, a town councillor from Algeria, prayed for a safe return to his sunny home after his stint as an officer on the north-west frontier.

Over at Corbridge (Coria), just south of Hadrians Wall, Diodora described herselfin Greekas a high priestess on the altar she dedicated to the exotic oriental cult of Herakles of Tyre. She probably came from Asia Minor. Further east along the Wall at South Shields (Arbeia), Barates, a Syrian merchant, erected a handsome tombstone in honour of his British wife, a freedwoman called Regina.

Many who came to Britannia as high-ranking officers and officials were cultured and affluent men who enjoyed remarkable careers: men such as the slick and extremely rich Spaniard L. Minicius Natalis, who arrived in Britain in about AD 130 fresh from winning a four-horse chariot race at the Olympic Games. Would he have been appalled by life on this gloomy old island or been thrilled by the hunting, the famously sensitive noses of the hounds, and the archaic skill of the British charioteers who, as late as AD 83, had ridden their war chariots into battle against the Romans at Mons Graupius? It was in thinking about these diverse characters from such varied backgrounds that I began to wonder not just why they came here and what they might have made of this place but how they got here. What means of transport would they have taken? How long would it have taken them to get to Britain? How would they have got about the place when they arrived?

In attempting to evoke a journey to Britain in the Roman period, to capture the flavour of life for any of these people, the first hurdle is to confront the fact that Roman Britain spans a period of more than 450 yearsbeginning with Julius Caesars expeditions in 55 and 54 BC. This is the same amount of time that separates the era of Elizabeth Is reign from the the present day. Unsurprisingly during these centuries, both the Roman world and Britain changed profoundly: the Roman Republic fell and chief citizens became emperors. The empire expanded greatly and then was carved up several times over. Christianity triumphed over paganism, and power shifted ever further east, away from Italy until, in AD 330, the Emperor Constantine the Great dedicated Constantinople in his name as the New Rome.

For these reasons a journey in the first or early second centuries would have been profoundly different to one in the third and fourth centuries, featuring personalities from widely different backgrounds, both in terms of their country of origin and their social class. Their journeys would have taken them along different routes, and those travelling in the later period would have had to face more uncertainties, including a greater threat of pirates on the seas and armed conflict on land. Britain was also administered in completely different ways; the province was split in two in the early third century, and into four in the fourth century, and her political and economic organization changed markedly.

Next page