PREFACE

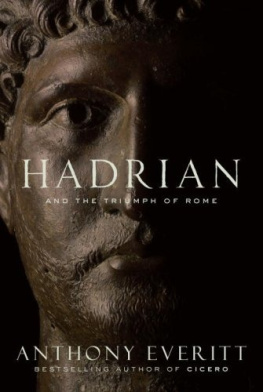

Hadrian lived through tempestuous and thrilling times. He ruled the Roman empire in the second century A . D . and has a good claim to have been the most successful of Romes leaders. An experienced soldier and a brilliant administrator, he presided over the empire at its height.

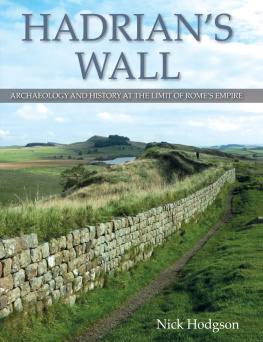

He had two very good ideas, which helped to ensure that the empire had a long and successful future. First of all, he saw that Rome could not go on expanding. The empire, which stretched from Spain to Turkey, from the Black Sea to the Maghreb, was unmanageable enough as it was and he ruled out any more wars of conquest. As a demonstration for the literal-minded, he built walls along all the frontiers, except where natural boundaries already existed in the shape of rivers and mountains. On this side was civilization and the pax Romana; on the other lay the untamed territory of barbarism, of everything that was not-Rome. In Germany the wall was a wooden palisade, long since gone, but in northern Britain, for want of trees, it was built of stone and remains today one of the most evocative symbols of Roman dominion.

Hadrians second idea stemmed from his love of Greece. The eastern half of the empire spoke Greek and boasted a culture that went back to Homer. Rome in the west was the superpower of the Mediterranean basin and commanded irresistible armies. Hadrian took steps to transform the empire into a joint project, where the cultural and the military, art and power, could meet on equal terms. He brought Greeks into government and through massive building projects developed Athens into the empires spiritual capital.

In these two ways Hadrian ushered in, as Edward Gibbon wrote, perhaps a little fulsomely, in his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, the fair prospect of universal peace. He and his successors, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius, both of whom he appointed and who continued his policies, persisted in the design of maintaining the dignity of the empire without attempting to enlarge its limits. By every honourable expedient, they invited the friendship of the barbarians; and endeavoured to convince mankind that the Roman power, raised above the temptation of conquest, was actuated only by the love of order and justice.

This is my third Roman biography and completes a triptych. Cicero traces the fall of the old flawed Republic, and Augustus the establishment of rule by one man. Here now is the story of an emperor who brought a period of disorder and military aggression to a prosperous conclusion, and showed how monarchy could be compatible with good governance. Some of the personalities of the previous books, although long dead, put in cameo appearances, especially Augustus, whom Hadrian greatly admired and emulated.

I attempt not only the portrait of a man, but of an age, during which an unstable system of power, proceeding by fits and starts, managed to regain its balance. While the fall of the Roman Republic is a well-trodden pasture, for many readers the epoch from the end of Nero to the reign of Hadrian is terra incognita; they may find its bloodstained twists and turns all the more exciting for the personalities and the plot being novel.

Hadrian was by no means the first Roman to be extravagantly philhellene. For centuries most members of the ruling elite had been bilingual in Latin and Greek. That poetical narcissist the emperor Nero had had much the same unifying idea as Hadrian, but been incompetent to carry it out.

In Hadrians childhood, two unforgettable events took place: the Colosseum, that vast humanities slaughterhouse, opened its doors to the public, and the destruction of Pompeii seemed to prefigure how the world would end.

In his late teens Hadrian witnessed the emperor Domitians murderous culling of the ruling class. Civil strife was narrowly avoided after the emperors assassination, and in due course Hadrians cousin and onetime guardian, Trajan, a popular general, took up the reins of power. From Trajan, the young man learned the art of soldiery in two terrifying campaigns against a fierce barbarian kingdom on the far side of the Danube. The reliefs that wind their way up Trajans Column in Rome follow these tumultuous events. Like carved newsreels, they speak across time with the immediacy of a CNN report.

Then followed triumph and, in equal measure, disaster. In a campaign that has a sharp contemporary resonance, Trajan invaded the Parthian empire (roughly what is now Iraq). Victory was swift, for the Parthians offered little or no resistance. But then insurgencies broke out across the eastern empire. Sick at heart and in body, the emperor handed over command to his former ward, and soon afterward died on the journey back to Rome.

The legions acclaimed Hadrian as the new emperor. It had been a long, arduous, and perilous apprenticeship. But now, at the age of forty, the new master of the known world was eager to make history, and was determined that no one should stop him. An indefatigable traveler, Hadrian spent as much time as possible on the road, inspecting everything and reforming everything. The frontiers were secured, the army trained, the laws codified, infrastructure improved, the economy fostered.

There was a terrible exception to this record of benevolent success. Hadrians politics had a dark side. The one people that refused to be reconciled to the imperial system was the Jews. A great revolt against Rome broke out. The outcome was a catastrophe for the rebels; according to one estimate, many thousands of Jews were killed, and many others driven from the land. In an attempt to annihilate this thorny and unyielding race from memory, Hadrian renamed Jerusalem and replaced Judaea with a newly minted word, Palestine. All Jews were forbidden from entering their own capital city. It took two thousand years before they were able to return and resume their independence.

Hadrian is the most enigmatic of ancient Romans.

Why is so little said of him? Why have his achievements been so sparsely celebrated? Although he has attracted scholarly attention, the last full-dress biography in English for the general reader appeared as long ago as the 1920s. One explanation of this silence lies in the mans prickly personality. A fine administrator, Hadrian was brave, intelligent, and, on the main political issues of the day, astute. But he was also irritable and excessively pleased with himself: like many talented amateurs, he took malicious fun in contradicting experts. Hadrian sometimes turned on his friends and threw them over without regret. That great classical historian of the nineteenth century Theodore Mommsen found him repellent and venemous.

There was an even more damaging threat to Hadrians posthumous reputation. Hadrian had a doomed love affair with a beautiful Bithynian boy, Antinous, who drowned mysteriously in the Nile. Victorian and early-twentieth-century commentators shied away from the embarrassing topic of same-sex relationships. One of them argued, hopefully, that Antinous was the emperors illegitimate son. Bastardy was bad enough, to be sure, but almost respectable when compared with the love that dared not speak its name.