IMPERIAL

TRIUMPH

MICHAEL KULIKOWSKI is Professor of History and Classics at Penn State University, where his research and writing ranges widely across ancient and early medieval history. He is a regular contributor to the London Review of Books. His books include Romes Gothic Wars, described by Bryn Mawr Classical Review as exceptional and by Military History Review as breezy and animated, yet authoritative. He is currently writing Imperial Tragedy on the history of the empire from the Constantinian legacy to the Destruction of Roman Italy in 568, to be published by Profile in 2018.

By the same author

Late Roman Spain and Its Cities

Hispania in Late Antiquity

Romes Gothic Wars:

From the Third Century to Alaric

IMPERIAL

TRIUMPH

THE ROMAN WORLD FROM HADRIAN TO CONSTANTINE

MICHAEL KULIKOWSKI

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Michael Kulikowski, 2016

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978 1 84765 437 3

For Ellen and David

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I n a survey of this scale, ones debts are always numerous and often nebulous: practically everyone whos ever taught you something should have a place, and that kind of list has no limits. So Ill start by thanking John Davey, who commissioned the volume, Penny Daniel at Profile, and the exceptional teams both there and at Harvard University Press who brought it to fruition. Erin Eckley at Penn State has made it possible for me to do my job and still find moments to write. I am grateful for the research support Ive received from my university, and for support from the Fund for Historical Studies in the Institute for Advanced Study, where I have spent a happy year as a Member of the School of Historical Studies and where the final draft of this book was completed.

In much broader terms, Id like to thank those who taught me most of what I know, even though I often didnt realise Id learned it until years later and even though some of them would probably say I havent learned a damn thing, least of all from them: Tim Barnes, Palmira Brummett, Jack Cargill, Angelos Chaniotis, Todd Diacon, Martin Dimnik, Jim Fitzgerald, Patrick Geary, Walter Goffart, Maurice Lee, Lester Little, John Magee, Ralph Mathisen, Sandy Murray, Walter Pohl, Roger Reynolds, Danuta Shanzer, Alan Stern, David Tandy and Susan Welch. Also my family, above all my grandmothers, as well as Oliver and Melvin.

Thanks go likewise to friends and colleagues whove inspired me, in ways too diverse to parse, and who have little in common save that fact: David Atwill, Bob Bast, Mia Bay, Joe Boone, Kim Bowes, Sebastian Brather, Tom Burman, Craig Davis, Deborah Deliyannis, Bonnie Effros, Hugh Elton, Catherine Higgs, Gavin Kelly, Maura Lafferty, Chris Lawrence, Hartmut Leppin, Mischa Meier, Eric Ramrez-Weaver, Josh Rosenblum, Kathy Salzer, Sebastian Schmidt-Hofner, Tina Shepardson, Denise Solomon, Roland Steinacher, Paul Stephenson, Ellen Stroud, Carol Symes, Philipp von Rummel, Ed Watts, Clay Webster, David Wiljer and Christian Witschel. I owe Nicola Di Cosmo and Michael Maas special thanks for inviting to me to their symposium on Worlds in Motion at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton in 2013 (now to be published as Eurasian Empires in Late Antiquity); it opened my eyes to a new and unimaginably rich historical world. To my colleagues in the Penn State history department, as whose head I served during the years I was writing this book, I owe an inexpiable debt, both for tolerating my periodic inattentions and for reminding me, continually and in big ways and small, that structural and social constraints operate on every system of governance. As much as all the foregoing, however, I would like to single out three fellow historians who have influenced my thinking about history, about our profession, about what we as scholars owe society so deeply that Im rarely conscious of their having done so until I find myself unexpectedly reminded, and ever the more grateful, for it. To Richard Burgess, Guy Halsall and Noel Lenski: thanks.

Finally, the books dedicatees, better friends than I ever expected to have.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

While every effort has been made to contact copyright-holders of illustrations, the author and publishers would be grateful for information about any illustrations where they have been unable to trace them, and would be glad to make amendments in further editions.

Maps

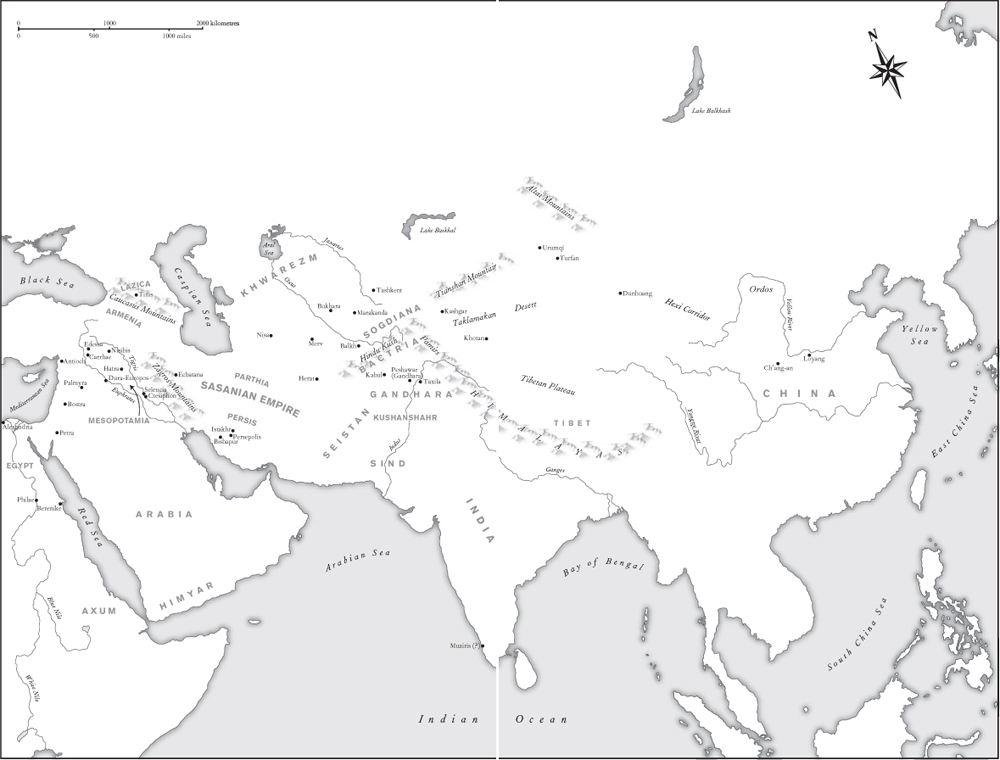

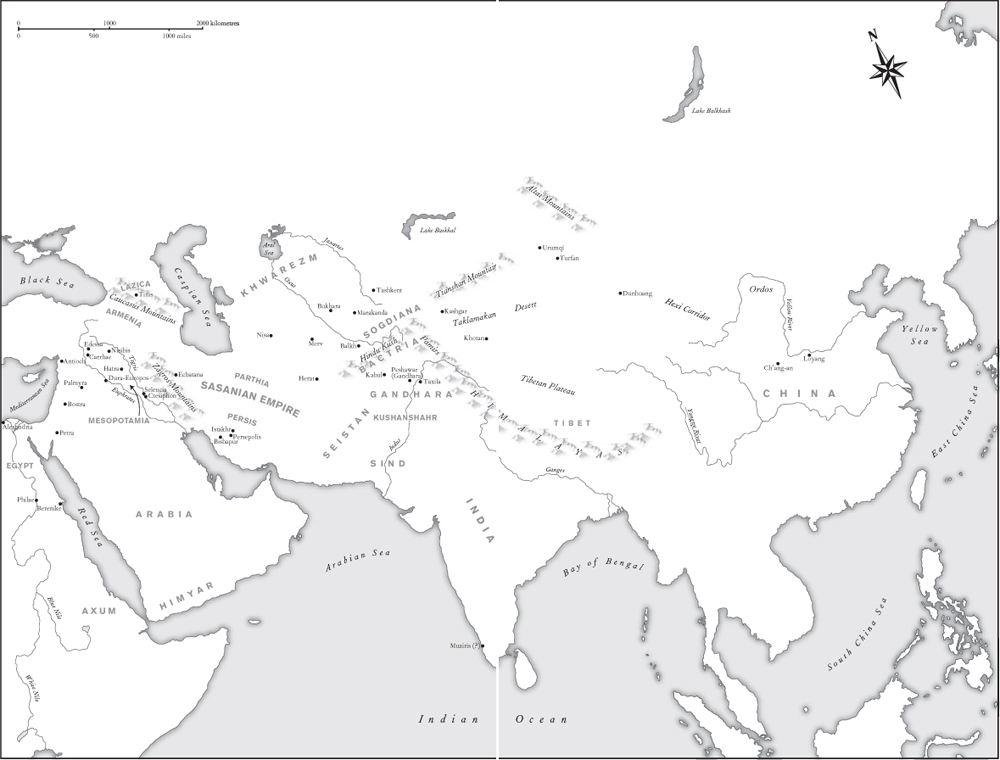

The Eurasian World

The Roman Empire under Hadrian

The Roman Empire under the Antonines

The Severan Empire

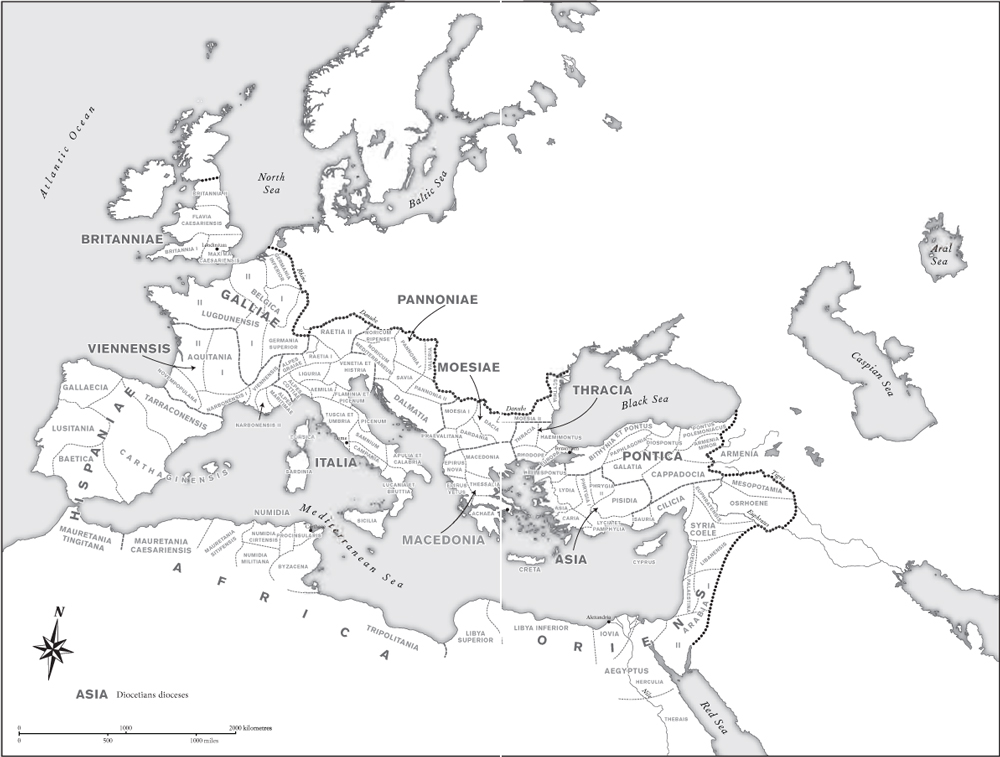

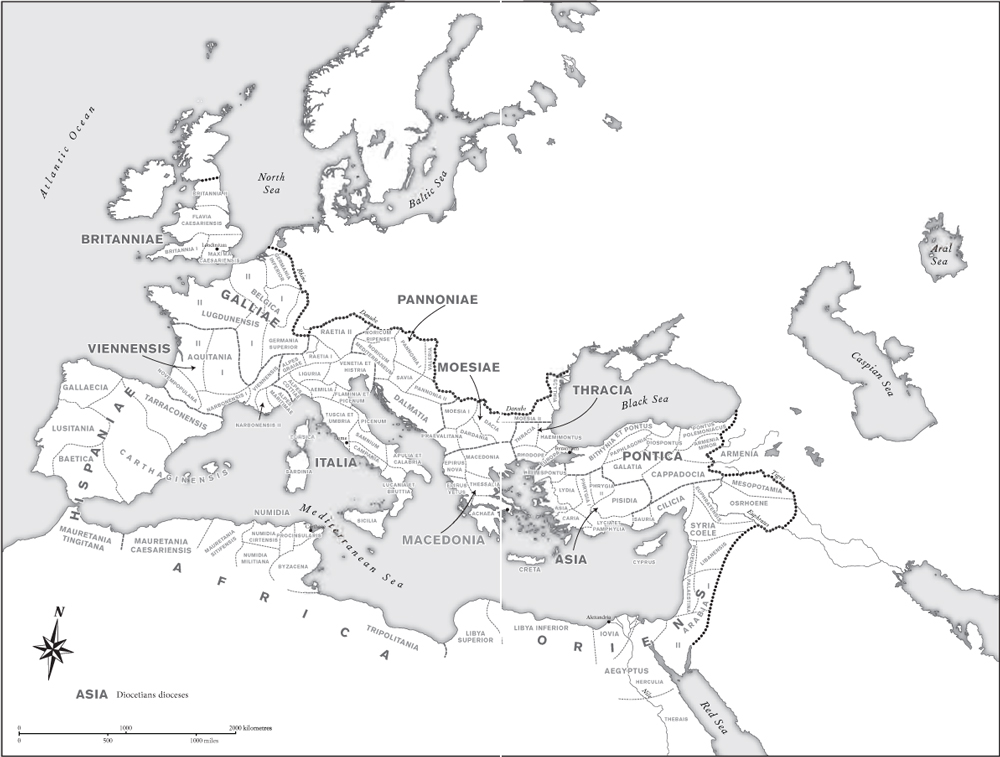

The New Empire of Diocletian

The Parthian Empire

The Sasanian Empire

INTRODUCTION

R ome started out as a very ordinary village on the Tiber river in central Italy perhaps a millennium before our story begins. For centuries, it was largely indistinguishable from its neighbours but, in the fourth century BC, it began aggressively to expand into the rest of the peninsula. Its leaders were magistrates elected each year by a citizen population whose votes were weighted to give the rich and powerful a decisive voice in their outcome. The system was in some respects genuinely representative of the citizenrys wishes and, virtually every year, the citizen army marched out, led by two elected consuls, to fight an enemy. Conquest accelerated in the third century BC, and a hundred years later Rome was unquestionably the superpower of the Mediterranean world. At the same time, however, the republican constitution began to break down, as rival generals tried to grab a monopoly of power for themselves and their cronies. The republic was destroyed by decades of civil war and, by the end of the last century BC, the sputtering machinery of republican government was replaced by the rule of one man, Augustus, the first Roman emperor.

Next page