Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

To my students

AUTHORS NOTE

Ancient names are generally spelled following the style of the standard reference work, The Oxford Classical Dictionary , 4th ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

Translations from the Greek or Latin are my own, unless otherwise noted.

All dates are AD unless noted otherwise.

CHRONOLOGY OF THE EMPERORS

THE REIGNS

All dates AD unless stated otherwise.

Augustus | 27 BC14 AD |

Tiberius | 1437 |

Nero | 5468 |

Vespasian | 6979 |

Trajan | 98117 |

Hadrian | 117138 |

Marcus Aurelius | 161180 |

Septimius Severus | 193211 |

Diocletian | 284305 |

Constantine | 306337 |

PROLOGUE

A NIGHT ON THE PALATINE

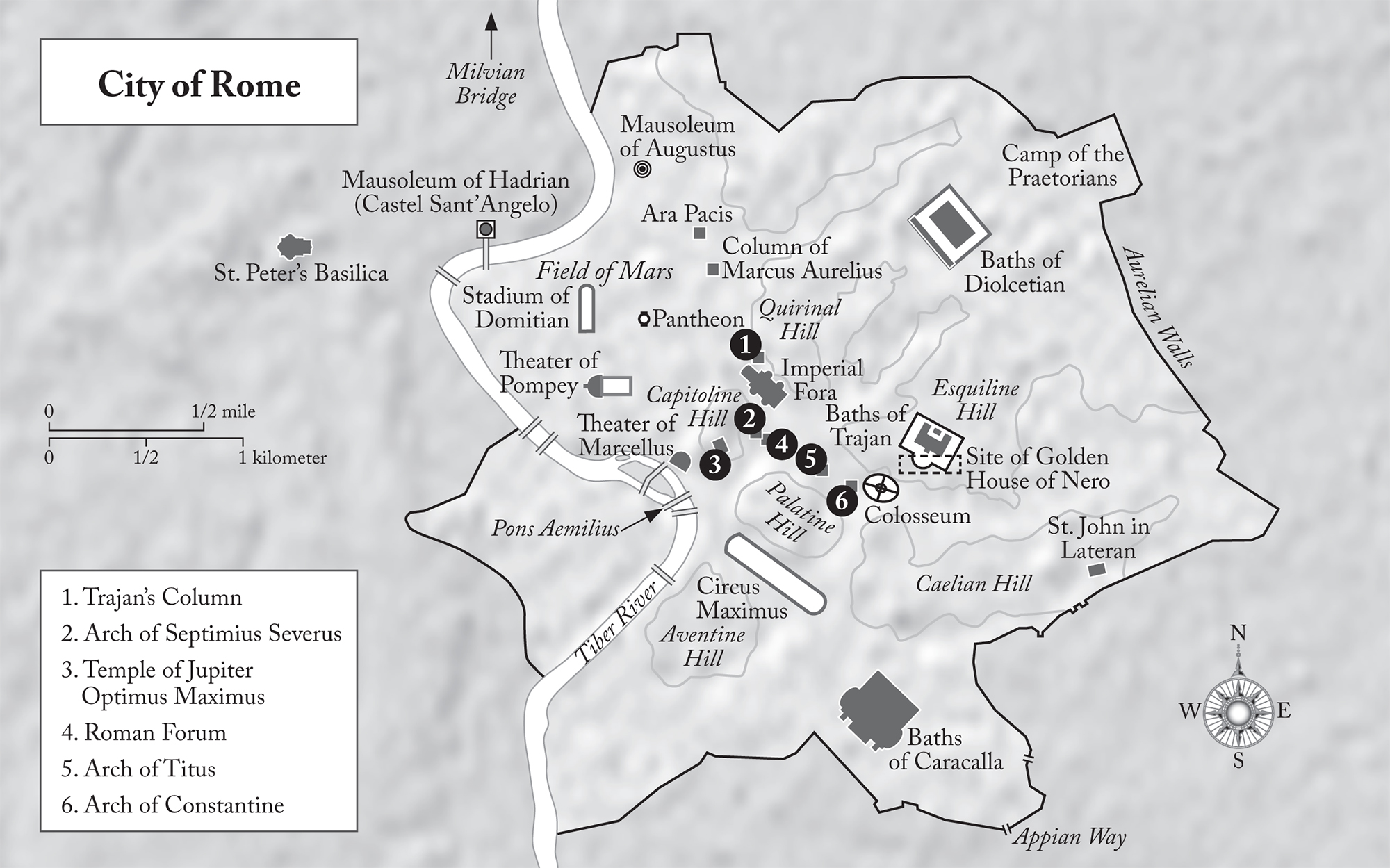

It is night on the Palatine Hill, a historic height in the heart of Rome. Imagine yourself alone there after the tourists go home and the guards lock the gates. Even during the day, the Palatine is quiet compared with the crowded sites in the valleys below. At night, alone and given an eerie nocturnal run of the place, could you rouse imperial ghosts?

At first sight, the answer might seem to be no. The breezy, leafy hilltop lacks the majesty of the nearby Roman Forums columns and arches or the spectacle of the Colosseum and its bloodstained arcades. The ruins on the Palatine appear as a confusing jumble of brick and concrete and misnomers. The so-called Hippodrome, or oval-shaped stadium, for example, is really a sunken garden, while the House of Livia did not belong to that great lady.

But look more closely. Give rein to your imagination, and you will understand why the Palatine Hill gave us our word palace. It was here on the Palatine that Romes first emperor planted the flag of power and where, for centuries, most of his successors each ruled over fifty million to sixty million people. It began as a modest compound for the ruler and his family and a temple to his patron god. Then it turned into a series of ever-grander domus , or houses. They were palatial estates used not only as homes but also for imperial audiences, councils, embassies, morning salutations, evening banquets, love affairs, old and new religious rituals, conspiracies, and assassinations.

In their day, they bespoke magnificence. Their walls were lined with colored marbles from around the empire. Their columns gleamed with Numidian yellow, Phrygian purple, Egyptian granite, Greek gray, and Italian white. Gilded ceilings rose high over tall windows and heated floors. One banquet room seated thousands while another revolved. Water flowed in fountains and pools fed by the Palatines own aqueduct. Some rooms looked over the chariot races in the Circus Maximus in the valley to the south, offering a kind of skybox.

Perhaps a modern night visitor to the Palatine could imagine a famous dinner party with the emperor at which one guest said he felt like he was dining with Jupiter in midheaven. Or a less pleasant banquet when the emperor had the walls painted black and the dining couches laid out like tombstones, leaving the terrified guests in fear of their liveswhich were spared. Or we might remember the rumor that another emperor turned the palace into a brothela salacious but not very credible tale. We might think of the palace steps, where one emperor was first hailed and another announced his abdication. We might think of the grand entrance, where one new emperors wife proclaimed her resolution not to be corrupted, or the back door, where another emperor slinked home, barely escaping with his life from a food riot in the Forum. Or we might imagine a Senate meeting in a palace hall, with the emperors mother watching through a curtain. Or the covered passage where a crowd of conspirators murdered a young tyrant. They all happened here.

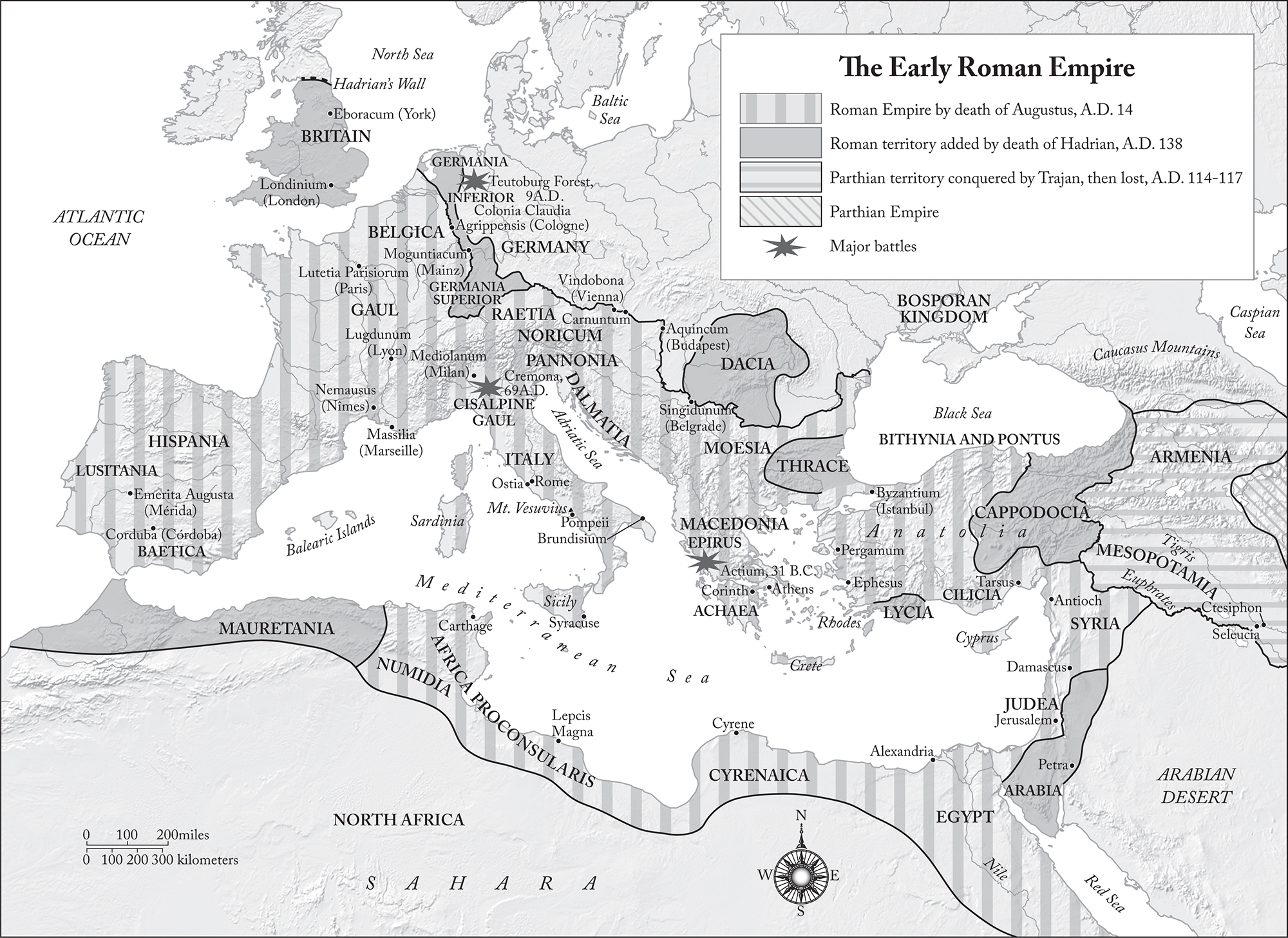

From the Palatine, the emperors ruled what they called the world, a vast realm stretching at its height from Britain to Iraq. Or at least they tried to rule it. Few excelled at the grueling job. The imperial administration took care of ordinary business, but crises proved a challenge. Many emperors turned out not to be up to the task. A few did extremely well. They brought to bear, in equal measure, ambition, cunning, and cruelty.

They brought family, too. The Roman emperors ran one of historys most successful family businesses and one of its most paradoxical. In order to concentrate power in trusted hands, the imperial family made full use of its members, including women. As a result, mothers, wives, daughters, sisters, and mistresses enjoyed what some might consider a surprising amount of power. But it was sometimes an unhappy family, with forced marriages common and infighting and murder hardly rare. It was, moreover, a family whose definition was loose and flexible. More emperors came to the throne from adoption than by inheriting it from their fathers, and not a few seized power in civil war. It was both the empires glory and curse that succession was often contested. It opened the door to talent and to violence.

The first emperor, Augustus, set the tone. Adopted by the founder of the familys fortune, his great-uncle and Romes last dictator, Julius Caesar, Augustus had to fight a civil war in order to prevail. Indeed, his wife, Livia, eventually perhaps the most powerful woman in Roman history, was once a refugee in that war and had run away from the man she eventually married.

The following pages tell the story of ten who ruled. They were Romes most capable and successful emperorsor, in the case of Nero, at least one of the most titillating, and even he was a great builder. Success was defined variously according to circumstance and talent, but all emperors wanted to exercise political control at home, project military power abroad, preside over prosperity, build up the city of Rome, and enjoy a good relationship with the divine. And every emperor wanted to die in bed and turn over power to his chosen heir.

We begin with the founder, the first emperor, Augustus, and end about 350 years later with the second founder, Constantine, who converted to Christianity and created a new capital in the East, Constantinople (todays Istanbul, Turkey). Roughly halfway in time between the two men came Hadrian, who called himself a second Augustus and who did more than most to make the empire peaceable and to open the elite to outsiders. Alas, Hadrian was also tyrannical and murderous. In that, he was not unusual.

Next page