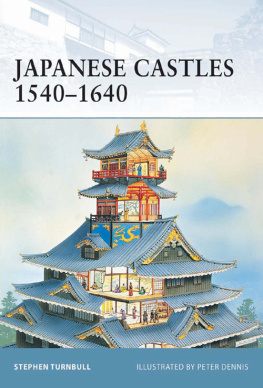

Fortress 67

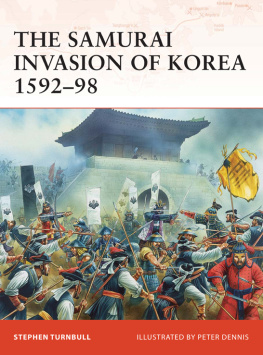

Japanese Castles in Korea 159298

Stephen Turnbull Illustrated by Peter Dennis

Series editors Marcus Cowper and Nikolai Bogdanovic

Contents

Introduction: the very short history of the wajo

The invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1597, the attempt at occupation between those two dates and the desperate rearguard action late in 1598 together make up a military operation unique in Japanese history. Apart from numerous pirate raids on China and Korea, some of which were very large in scope, and the annexation of Ryukyu (modern Okinawa prefecture) by the Shimazu clan in 1609, the Korean expedition remains the only occasion within a period of 1,000 years during which the destructive energies of the samurai (Japans warrior class) were expended on a foreign country.

Japans Korean expedition known to Koreans as the Imjin War was also the last military campaign to be set in motion by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (153698), and was to prove a disastrous end to the glorious military career of a brilliant general who is regarded as Japans equivalent of Napoleon Bonaparte. Having risen from the lowest ranks through a mixture of skill and opportunistic cunning, Hideyoshi was adored by his subordinates, who served him with a keen loyalty to a soldiers general that transcended the legendary fidelity expected of a samurai. In this Hideyoshi had set them a fine example when he served as the most loyal and talented member of the inner circle of generals under Japans first unifier, Oda Nobunaga (153482). Nobunaga, an early enthusiast for the firearms introduced from Europe in 1543, had transformed Japanese warfare, and had taken the first steps towards reuniting the country from the patchwork of competing petty daimyo (feudal warlords) whose squabbles had given the age the name of the Sengoku Jidai, the Age of Warring States.

When Nobunaga was murdered in 1582, Toyotomi Hideyoshi became his avenger, and by a series of rapid offensives overcame his fellow generals to inherit Nobunagas former domains. Three massive campaigns followed: the invasion of the island of Shikoku in 1585; the conquest of the island of Kyushu in 1587; and the defeat of the powerful Hojo family near modern Tokyo in 1590. Within a year all the other daimyo had submitted to him, so that by 1591 Japan was reunited under the son of a peasant.

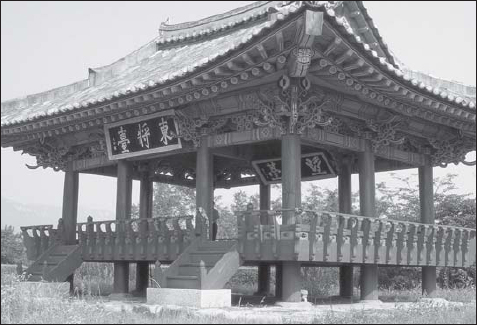

The Korean-style pavilion on the summit of the hill on which Dongnae wajo was built.

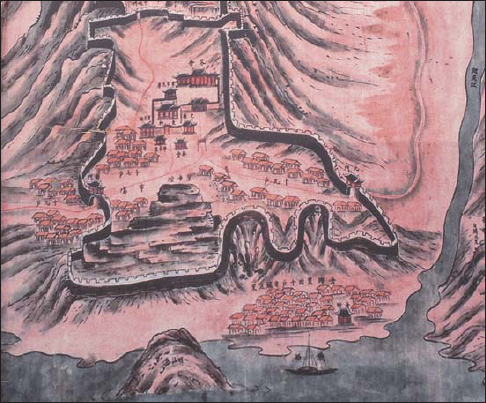

The wajo of Yangsan as viewed from the modern bridge over the Nakdong River near the foot of the hill on which was built the wajo of Hopo. Hopo shared with Yangsan the defence of the Nakdong above Busan. Yangsan wajo was built along the ridge of the two prominent hills in the middle distance.

If Hideyoshi had been content to stop there his place in Japanese history would have been assured. But his campaigns of the 1580s had involved the successful deployment of armies numbered in many tens of thousands and their safe transport by sea. By 1591 everything looked possible to him, even the conquest of China, a dream that he had entertained for several years. Geography, if nothing else, suggested that to carry out such an outrageous scheme which would have to be aimed at Beijing, the capital of the Ming dynasty a Japanese invasion would have to proceed via the Korean Peninsula. When the Korean king refused to allow the Japanese unimpeded progress through his country the planned Chinese war became a Korean war.

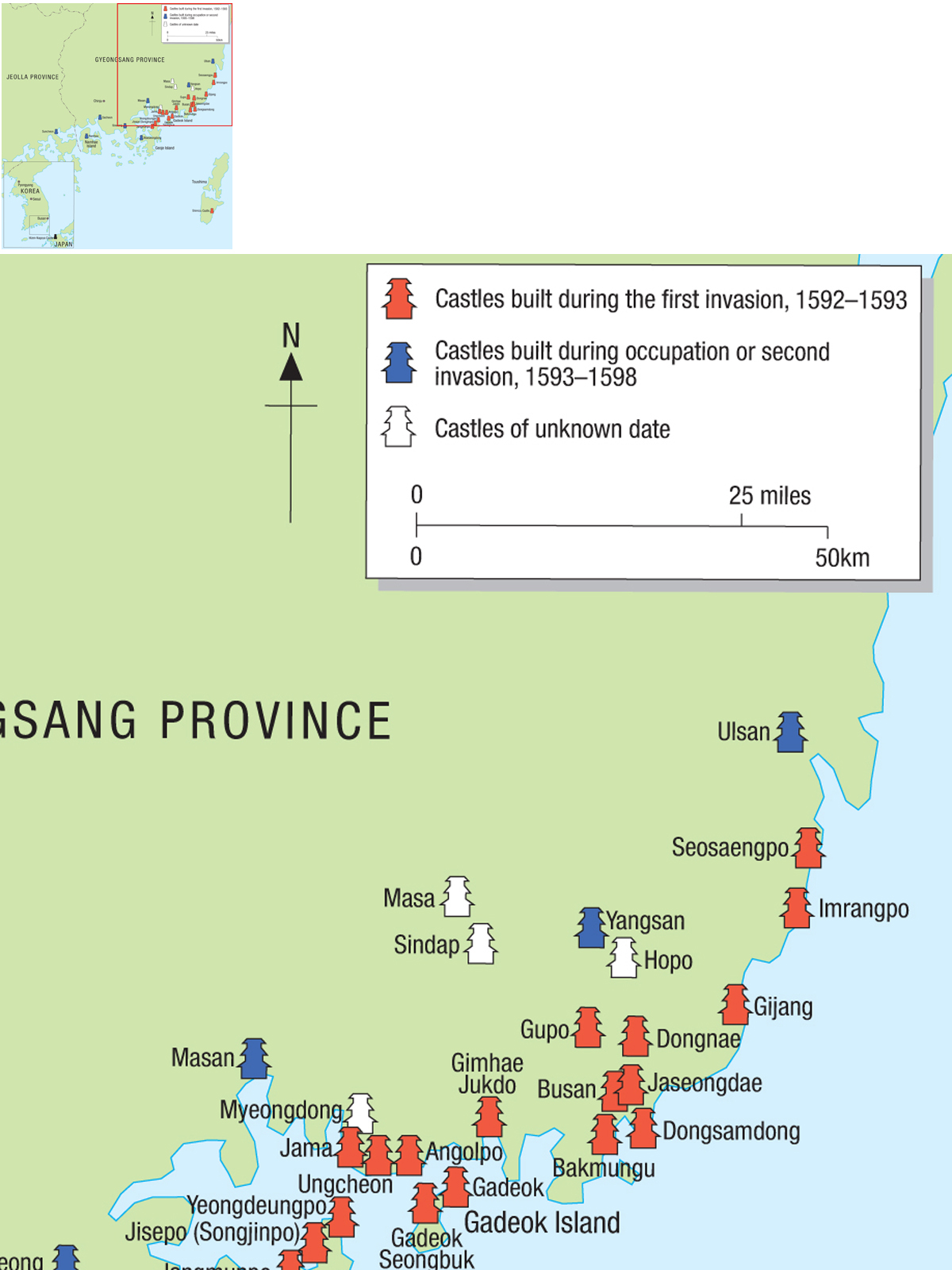

The invasion of Korea took place in May 1592 and involved an uninterrupted crossing of the sea via the islands of Iki and Tsushima. The first shots of the campaign were fired against the fortress guarding the harbour of Busan, a castle that would one day become one of the most important Japanese wajo. From here the First Division under Konishi Yukinaga proceeded northwards, taking two other future wajo at Dongnae and Yangsan. The Second Division under Kato Kiyomasa followed them along this route, while Kuroda Nagamasas Third Division landed further to the west across Busans great natural moat of the Nakdong River and captured Gimhae, another site that was to become a Japanese strongpoint.

A rapid advance followed, and within a few days Seoul, the Korean capital, had fallen to the Japanese. A delay at the Imjin River allowed the Korean king to escape to the Chinese border, but not long afterwards Konishi Yukinaga occupied Pyongyang, while Kato Kiyomasa set off on a campaign to pacify the north-east and to cross into Manchuria. The successful conquest of Korea was reported back to a satisfied Toyotomi Hideyoshi (who never left Japan during the entire campaign), and plans were rapidly drawn up for the occupation of Korea, the allocation of territory, the drafting of tax rolls and its inhabitants incorporation under Hideyoshis hegemony in much the same way that the Japanese daimyo had submitted to him in 1591.

It was at that point that the counterattack began, and Pyongyang, captured so easily by Konishi Yukinaga, was destined to be Japans last outpost on the road to China. Three developments were to thwart Hideyoshis dream of conquest. The first was the activity of Korean guerrillas, who were drawn from the shattered remnants of the army and fought under newly inspired leaders. The second was the series of naval victories won by the renowned Admiral Yi Sunsin, whose heavily armed turtle ships destroyed many Japanese vessels and disrupted communications with Japan. The third, and ultimately the most important development, was the intervention of Ming China. In a battle that was to prove the major turning point in the war Pyongyang was recaptured in February 1593. From this moment on the Japanese were involved in a fighting retreat. By the autumn of 1593 their invading armies had evacuated Korea, leaving behind a handful of garrisons to occupy their remaining toehold on Koreas south coast. The fortresses from which this defiant illusion was to be maintained for the next five years were the first of the wajo.

Map of the southern part of South Korea showing the locations of the wajo 159298.

The site of the wajo of Ulsan today, looking across the river from the south. The Japanese-style stone walls are obscured by the dense foliage. Ulsan marked the eastern end of the line and was incomplete when attacked by the Ming in 1598.