FORTRESS 5

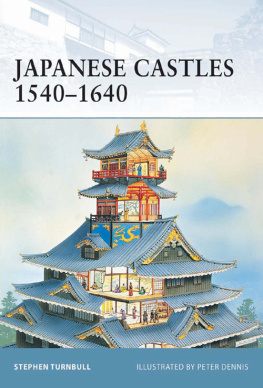

JAPANESE CASTLES 1540-1640

| STEPHEN TURNBULL | ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS |

| Sries editors Marcus Cowper and Nikolai Bogdanovic |

Contents

Introduction

Japanese castles as we see them today are not only final products of a long process of military evolution, but also evidence of a military revolution. In the latter half of the 16th century Japanese warfare was transformed. It changed from an activity characterised by the use of loosely organised troops wielding bows and arrows and defending largely wooden fortifications, to one that involved well-disciplined infantry units armed with guns, fighting from castles of stone. The similarities to the military revolution that was taking place in Europe at the same time are striking, but until the beginning of this period there had been no cultural contact between Japan and Europe.

Contact was made when a Portuguese ship was wrecked on the Japanese coast in 1543, and the two cultures soon began to realise how their widely separated worlds had been evolving in roughly similar ways. Both were experiencing warfare on a larger scale than ever before, which required the development of strong internal army organisation and good discipline, and both were seeing a move towards a preference for fighting on foot. Yet there were also some fascinating differences, at the same time that the European knight was giving up his lance for the pistol, the mounted samurai was abandoning his bow for a spear.

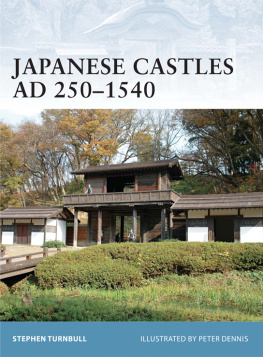

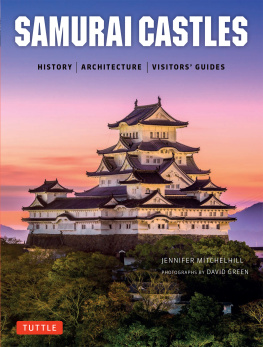

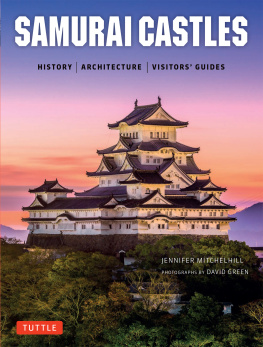

The castle of Shimabara in Kyushu, a fine example of the classic style of developed Japanese castle architecture, involving the elements of a moat, the all-important huge stone bases, which are the hallmarks of a Japanese castle, and the graceful superstructure. We see here one of the corner towers, and the long white small walls pierced with gun and arrow loops.

However, it is in the field of castles and fortifications that both similarities and differences are found in the greatest abundance. Italian visitors to Oda Nobunagas castle of Azuchi in 1579 compared it favourably with any contemporary European fortress, and remarked particularly on the richness of the decorations and the strength of the stone walls. As none of these early visitors were military men, rather merchants or priests, they cannot be expected to have commented upon Japanese castles from a position of technical knowledge, but it is abundantly clear from the impression given to them by the walls of Azuchi, Osaka and Edo, all of which were enthusiastically described in contemporary Jesuit writings, that they were making comparisons with existing structures in Spain or Italy.

So what were they actually comparing the Japanese castles to? By the mid-16th century the huge sloping stone walls that surrounded Verona, Sienna or Rome had become a recognised and vital part of the townscape of a successful city. They were the defining features of the trace italienne, the fortification style characterised by the use of the angle bastion, which was designed for artillery warfare and was the most important architectural innovation since the arch. The walls of fortresses such as Osaka certainly had much in common with the European system, but what the visitors did not know was that these curiously similar structures had a completely different developmental history, were built in a completely different way, and were designed to withstand attacks of a completely different nature.

The pages that follow will offer a detailed discussion on these points, all of which went towards making the Japanese castle into a unique form of defensive architecture that acknowledged its own culture and tradition, yet responded imaginatively to changing conditions of warfare. Like those in contemporary Europe, Japanese castles experienced conflict on a huge scale when all the theory behind them was tested to destruction in half a century of fierce civil war.

Japanese castles in their historical context

By the time that the first stone walls began to appear around Japanese castles, an innovation that can be seen from about 1550 onwards, Japan had already experienced intermittent bouts of civil war for almost 1,000 years. The key to understanding the reasons for such conflicts, and the nature of the Japanese castles that arose in response to them, involves an appreciation of Japans physical isolation from continental Asia. This protected her from some dangers, so that while China and Korea were being ravaged by the Mongol hordes in the 13th century, life was comparatively peaceful in Japan. Attempts to invade Japan were repulsed in 1274 and 1281, but this splendid isolation also meant that Japan could not expand into her neighbours territories to acquire more cultivable land, something that Japan was desperately short of. As the struggle for land grew, the possession of military force was the best guarantor of securing new lands and of then defending them against rapacious neighbours.

The establishment of the rule of the shogun (military dictator) after the triumph of the Minamoto family in the Gempei Wars of 118085 provided some measure of stability amid the rivalries, but invading Mongols, rebellious emperors (who resented the purely ceremonial role forced upon their sacred office by the shogun), family leaders whose wealth rivalled that of the shogun, peasant revolts and fierce religious fanatics all played their part in disrupting the theoretical calm. In 1467 the Onin War, so called from the nengo (year period) in which it began, broke out between two rival samurai clans. Kyoto, the Japanese capital, was laid waste and among the smouldering ruins of palaces and temples lay the blackened remains of shogunal prestige. From this time on any centralised authority that was left counted for little against the naked military might of the daimy (great names) as the rival warlords termed themselves. The next century and a half is known as the Sengoku Jidai (The Warring States Period), which lasted until Japan was reunified under the Tokugawa, a process that culminated in the siege of Osaka in 1615.

Some of the sengoku daimy had aristocratic backgrounds; others were the sons of tradesmen. Some acknowledged centuries of military tradition and service to the shogun, others learned rapidly how to swell the numbers of their armies by recruiting peasants as ambitious for advancement as they were themselves. Some ruled their territories from graceful mansions set among ancestral rice fields, but the determined ones built castles.

The castles of the early Sengoku Period looked very different from the graceful fortresses of later years. Most were just hastily constructed stockades on the tops of mountains, linked by paths and passes and looking down on vital roads. As time went by the stronger daimy absorbed their weaker enemies and the strength of their fortified bases grew to be seen as a vital element in this process. So single stockades became fortified complexes of wooden stockades that were combined across sculpted hillsides. Then stone was added, and stout gatehouses, towers and keeps began to arise. At the same time the unexpected contact with Europe introduced firearms to Japan, so instead of seeing only ranks of archers, battlefields began to witness ranks of arquebusiers. The samurai, who had traditionally been a mounted archer, had already adopted the spear to allow him to take the fight to dismounted missile troops. Now he began to dismount from his horse to fight beside the