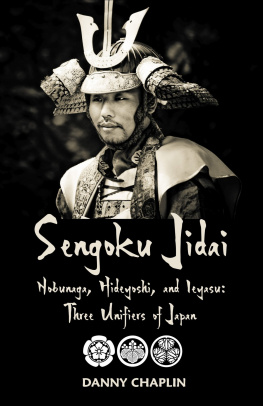

Sengoku Jidai

Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, and Ieyasu:

Three Unifiers of Japan

ALSO BY DANNY CHAPLIN

Strenuitas. The Life and Times of Robert Guiscard and Bohemond of Taranto: Norman Power from the Mezzogiorno to Antioch 10161111 A.D.

The Medici: Rise of a Parvenu Dynasty 13601537

Pietro Aretino: The First Modern

Sengoku Jidai

Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, and Ieyasu:

Three Unifiers of Japan

Danny Chaplin

Copyright 2018 by Danny Chaplin

All rights reserved.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

No part of this book may (except by reviewers for the public press) be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the author.

Title page art: a samurai of the sengoku period (or earlier) wearing a traditional kabuto helmet with ornamentation and haori surcoat over his armour.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Sengoku Jidai. Hideyoshi, Nobunaga, and Ieyasu : Three Unifers of Japan / Danny Chaplin

1. JapanHistoryUnification, 14671616

ISBN-10: 1983450200

ISBN-13: 978-1983450204

Printed by CreateSpace, An Amazon.com Company.

In memory of my beloved Grandfather

Frederick Charles Harris (19011980).

(the fruit never falls far from the stem).

Contents

APPENDICES

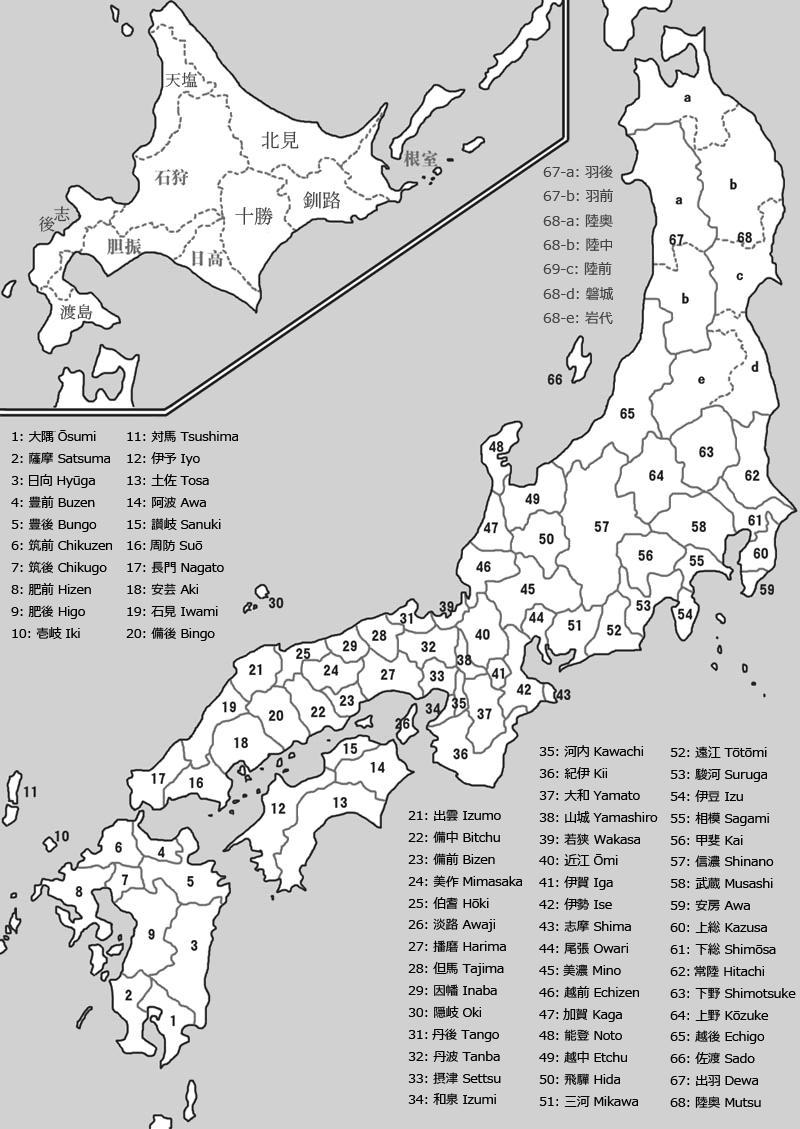

Provinces of Japan during the Sengoku Period.

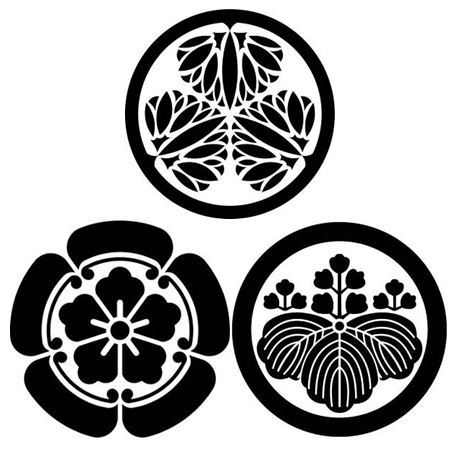

The Three Unifiers of Japan: Nobunaga piled the national rice cake of Japan, Hideyoshi kneaded the dough, and in the end Ieyasu sat down and gobbled it up . The fourth figure depicted is that of the traitor and assassin Akechi Mitsuhide.

Preface

In truth, this world is not eternally inhabited.

It is more transient than dew drops on leaves of grass, or the moon reflected in the water.

After reciting the poetry of flowers at Kanaya, all glory is now left with the wind of impermanence.

The Song of Atsumori

E ach year, on 19 October, the Kenkun Shrine in northern Kyoto commemorates the life of the first of Japans three great unifiers, Oda Nobunaga, in a festival called Funaoka Taisai. In a city famous for its countless festivals, Funaoka Taisai is worth seeing if one is in any way intrigued by the era of the samurai. On that date, which is the anniversary of the day in 1568 when Oda Nobunaga rode into Kyoto at the head of his army, local teenagers dress themselves up in authentic medieval samurai armour, stage a parade for visitors and sightseers, fly their Oda clan banners, and give noisy demonstrations of matchlock firearms. Afterwards, a famous twelfth-century noh drama entitled the Atsumori is performed. This play was a particular favourite of Nobunagas during his lifetime. He sang it, and danced it, and he reflected on its themethe ephemerality of human existence. Afterwards, when the actors have finished their performance, they make way for a demonstration by falconers of the ancient Suwa school of falconry, a tradition whichlike noh dramaalso extends back centuries to the era of the samurai. Falconry too was a pastime to which Nobunaga was inordinately attached. Indeed, Funaoka Taisai might conceivably be renamed the festival of all Oda Nobunagas favourite things.

The Kenkun Shrine itself is situated atop Mount Funaoka, a hill in northwestern Kyoto which is said to be the domain of Genbu, the tortoise deity of the north. During the 268 years of the Tokugawa Shogunate (16001868), the totalitarian state established by the third and final great unifier, Tokugawa Ieyasu, the memory of both Oda Nobunaga and his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi had been deliberately and systematically airbrushed by the Tokugawa from the national psyche. With the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate in the late 1800s, however, the emperor Meiji commanded that a new shrine be constructed for Nobunaga at Funaoka, a plot which had originally been reserved in the 1580s for his funeral rites, as well as an uncompleted temple. Meiji also ordered at the same time that Hideyoshis mausoleum and commemorative shrine in Kyotos Higashiyama-ku district both be restored to their former glory after two and a half centuries of abandonment and neglect.

The shrines huge Shinto torii (marking the boundary between the realms of the sacred and the profane) faces onto an ordinary and unassuming residential Kyoto street. Small box-like cars, ubiquitous in Japan, and grimy Yamaha motor scooters are parked beneath nearby suburban eaves. Further down the street are some of the more traditional style wooden homes of Kyoto but otherwise the scene is a modern one, this too being the result of Meijis modernising efforts. Fortunately the trek to Mount Funaokas summit is, for those of us who are no longer in our youth, a forgiving one and can be taken in easy stages as you enjoy the golden autumn leaves, or the spring sakura cherry blossoms, or the birdsong which can heard here year-round. Reaching the temple precincts you are transported to an altogether different, earlier, world. The shrines main hall or honden () slopes with the classic elegance of the nagare-zukuri style of temple architecture, its roof constructed from traditional cyprus ( hinoki ) thatch. The oratory or haiden incorporates portraits of eighteen of Oda Nobunagas thirty-six loyal vassals, most of whom we shall become familiar with in the course of this story.

Nobunaga was a great man, as great to Japan perhaps as Napoleon was to France, or Julius Caesar was to ancient Rome, but like these other great hegemons he was often a brutal and violent tyrant. Throughout his quest to pacify and unify the country, thousands of men, women and children were put to the sword and innocent family members of disobedient retainers were executed by either beheading or crucifixion. On one occasion he executed all six-hundred inhabitants and relatives of a vassal who had rebelled against him. On another occasion, on the flimsiest of evidence, he commanded his closest ally to order the ritual suicide of his eldest son. Fittingly perhaps, Nobunaga himself died a violent death, targeted for assassination in a bloody coup dtat by a resentful follower. Nevertheless, it was Nobunaga who successfully began the process of creating order from chaos in sixteenth-century feudal Japan which his two inheritors would ultimately complete.