THE S AMURAI

W ARRIOR

THE GOLDEN AGE OF

JAPANS ELITE WARRIORS

15601615

BEN HUBBARD

This digital edition first published in 2015

Published by

Amber Books Ltd

7477 White Lion Street

London N1 9PF

United Kingdom

Website: www.amberbooks.co.uk

Appstore: itunes.com/apps/amberbooksltd

Facebook: www.facebook.com/amberbooks

Twitter: @amberbooks

Copyright 2015 Amber Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-78274-194-7

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge.

All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

www.amberbooks.co.uk

Contents

A fourteenth-century century scroll depicts a dramatic battle between Minamoto and Taira samurai at the Rokuhara mansion in Kyoto.

Introduction

The period of Japanese history between 1550 and 1615 is often considered something of a golden era for the samurai. This is when the warriors reached the zenith of their powers and united the country under the sword. This in turn led Japan into a new epoch, where samurai underlings could rise through the ranks and become powerful leaders.

T hese warlords would then crush and conquer any clan that opposed them using the latest breakthrough in weapons technology the arquebus. When the smoke cleared, Japan entered an enforced period of peace that would last for over 250 years. But this peace would also herald the beginning of the end for the samurai, who without wars to fight became an irrelevant burden on the feudal society they had created.

The samurai first began as eighth-century warriors hired by the Emperor to subdue native barbarians who harassed the empires furthest frontiers. Their battles were often skirmishes fought at close quarters, and the warriors long, straight, thrusting sword proved utterly useless against them. Instead, the Emperors men had to adopt the fighting methods of the natives they were charged with subduing. This meant mounted duels with bows and arrows, and swords cast with a special curved edge for slashing at opponents on horseback.

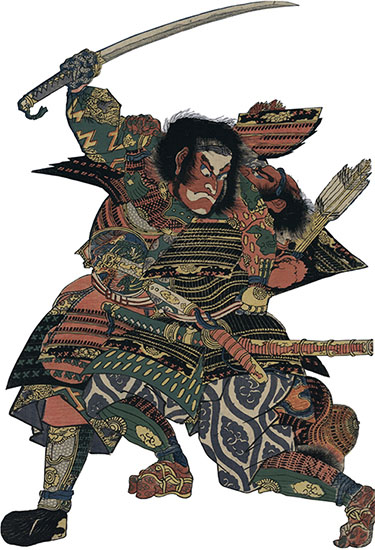

Early samurai combat consisted of a mounted archery duel between two warriors of equal rank. A swordfight on the ground would often follow.

Soul of the Samurai

This sword would later become the mighty katana, often called the soul of the samurai. Considered a spiritual extension of the warrior himself, the katana was a masterpiece of sword-making. The genius of the blade lay in its bimetallic makeup a hard cutting edge wrapped around a soft, flexible core. A samurais katana would only leave his side in death and even after the warrior order had ceased to exist the sword continued to be a symbol of the samurai ethos.Bushid, or Way of the Warrior, was the samurais code of ethics, which enshrined loyalty, honour, fearlessness, honesty and self-sacrifice. Brave warriors would display their bushid virtues on the battlefield, or die trying. Any samurai defeated in battle was expected to commit seppuku, or suicide by slitting open the stomach, as a matter of honour. To an extent, early battles between samurai warriors were considered an honourable exchange. They would start when one mounted warrior called out his rank, family name and achievements to attract an enemy warrior of similar standing. The ensuing archery duel was therefore viewed as consensual combat between gentlemen. Sometimes the foot soldiers fighting around these gentlemen warriors would even take a consensual pause and halt proceedings to admire a particularly heroic bout.

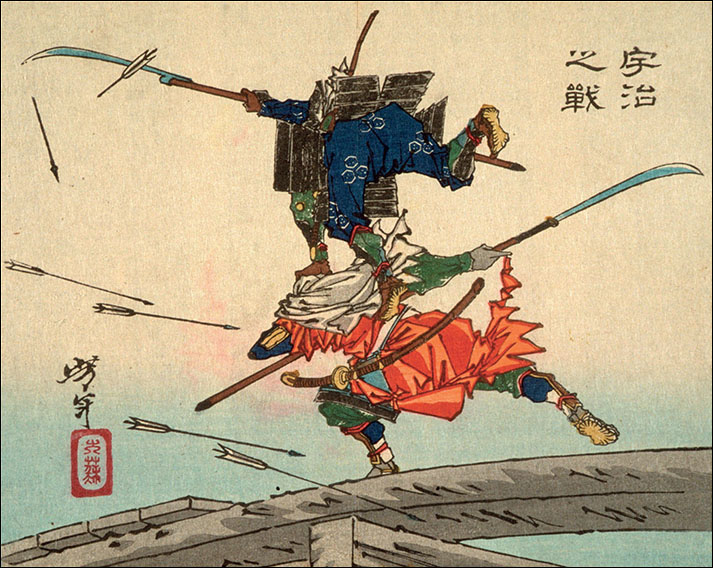

The Battle of Uji signalled the start of the Gempei War between the Minamoto and Taira clans. Here, naginata-wielding warrior monks stop the Taira from crossing Uji Bridge.

But this would all change in the mid-sixteenth century when a new weapon that washed up on Japanese shores would challenge notions of honour and heroism in battle. This was the arquebus, a matchlock firearm that arrived on board a shipwrecked Portuguese trading boat. The weapon was of enormous interest to samurai warlords known as daimy, the leaders of the warring samurai clans that now made up Japan. Known as the Sengoku Jidai, or the Age of the Country at War, this was a period of great upheaval. Many centuries previously the Emperor had his power wrested from his control by the Shgun, the barbarian-subduing commander-in-chief tasked with protecting him. But over time the Shguns position too had weakened. Now, titles were all but meaningless in the face of the burgeoning military might of the daimys.

The sixteenth century rise of the daimys was the first time in samurai history that a warlord without aristocratic blood could seize power and rule over Japan. This was so extraordinary that it even had its own name: gekokuj, or the low overcomes the high. One of the most famous cases of gekokuj was Oda Nobunaga (153482), also known as the first great unifier of Japan. Nobunaga was a young upstart who took great risks in war and won the ultimate reward: domination of the country and the majority of the clans that opposed him. Nobunagas rapid and often brutal ascendancy to power was aided in no small part by the arquebus. Unlike some of his more gentlemanly rivals, who used the gun as an auxiliary weapon from their back lines, Nobunaga made the arquebus the central element of his armies. He first put the weapon to devastating use in the 1575 Battle of Nagashino. Here, protected by palisades, three frontlines of warriors delivered rotating volleys of arquebus fire to mow down the enemys charges. After this assault, samurai were able to slip through gaps in the palisades and finish off any survivors with their swords.

Kusunoki Masashiges statue stands guard outside Tokyos Imperial Palace. Masashige immortalized himself by leading an army into a battle he knew could not be won.

The End of Honour

News of the battle astounded samurai veterans. It was a shock to think that Nobunagas sudden supremacy had apparently come to pass because of the arquebus. The weapon itself was considered to be offensive and dishonourable by bushid purists. Here was a weapon that a lowly foot soldier could learn to use in a day to take down a mounted samurai gentlemen who had spent his life training in the arts of war. But in the end, this complaint represented the last cry of a dying breed of samurai aristocrats who were losing their place to the low.