For Mum

Contents

S amurai were the ancient fighting class of Japan; a martial elite which ruled the country for over 700 years. From their early beginnings as barbarian-subduing soldiers, the samurai would rise to prominence as large warrior clans, powerful enough to wrest control from the very emperor they were charged with protecting. The samurai would go on to become an aristocratic caste and lived according to a strict code of honour called bushid , or way of the warrior. Bushid advocated honour, loyalty, pride and fearlessness in combat, and those who broke the code were expected to kill themselves.

A samurai would showcase his bushid virtues on the battlefield, seeking out a worthy enemy warrior to engage in one-to-one combat. To find a suitable opponent of equal rank and social standing, a samurai would call out his own name, position and accomplishments. When a response came, the warrior, adorned with flags and family crests, would once again yell out his name and charge into the fray.

The warriors would first engage each other in a mounted archery duel. This required a great amount of skill and training, as a rider had to release the reins to fire arrows while maintaining control of his horse. If neither party was victorious with the bow, they would dismount and continue fighting on the ground with swords, daggers and bare hands if necessary. This was a fight to the death, and contests between two famous samurai often created a pause in the fighting as soldiers from both sides watched. A samurais achievements in war were of paramount importance: the victorious fighter would chop off his opponents head and add it to his tally to be inspected later by his lord, shgun or emperor.

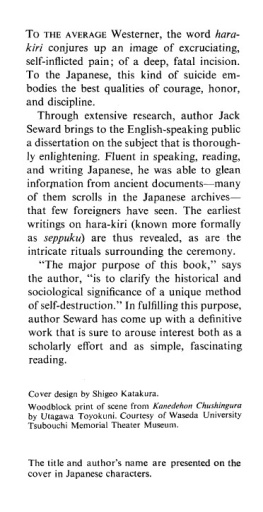

Samurai would rather die than be defeated and those not killed on the battlefield would be expected to perform seppuku , more commonly known today as hara-kiri (cutting the stomach). The ritual still provides a grisly source of fascination for Westerners, even centuries after the tradition was outlawed in Japan. Seppuku was always committed as a display of honour: it prevented the dishonour of capture and decapitation by the enemy; it helped to restore honour to a disgraced samurai; and, when used as a form of capital punishment, it allowed a condemned warrior to die an honourable death. Seppuku is considered to be one of the most painful ways for a human to die, and the bravest samurai were considered to be those who created the largest gaping wound or, better still, left viscera hanging from it.

The bloodiest period of samurai history undoubtedly took place during Japans medieval age (1185 c .1600), when bitter inter-clan conflicts and civil war wracked the country. It is ironic, then, that instances of seppuku actually increased in the seventeenth century, during an enforced period of peace. While the country prospered during this time, the ruling samurai class, which was paid a national dividend to stand battle-ready, became slowly defunct. Without wars to fight, warriors found themselves doing the unthinkable taking employment as teachers, bureaucrats and umbrella makers. Other samurai became rnin masterless warriors destined to roam aimlessly around Japan, searching for work as hired hands and fighting with one another. Seppuku became a wholly common occurrence in the seventeenth century, used as both a form of capital punishment and a deterrent to keep bored samurai in check.

The bar for obligatory seppuku at this time was set painfully low insulting a superior, harbouring Christians and brawling all received the same sentence of death by suicide. As a further hindrance to bad behaviour, a law was passed that made both parties in a violent argument equally responsible, regardless of what the dispute was about or who caused it. As the use of seppuku as capital punishment increased, so did the protocol for the elaborate ceremonies that surrounded it. For those about to die, white robes, final meals and paper for death poems were provided, as well as a nominated second to perform decapitation before the pain became too great.

Instead of indulging in street scuffles and bar brawls, samurai were encouraged to turn their attention to more intellectual and spiritual pursuits calligraphy, poetry, tea ceremonies and the teachings of Buddha. Numerous texts on bushid were produced during this period, many of them reflective and highly philosophical. This literature mainly concentrated on what it meant to be a samurai warrior, rather than providing practical military applications of how to perform as one. The heroic exploits of great samurai were also recounted with wistful and romanticised flourishes; the most celebrated warriors were unshakably loyal, educated in the arts of war, indomitable on the battlefield and, oddly, often fated to lose. Fidelity until death was considered the most important bushid virtue, and there was a particular appeal in the blindly obsequious samurai who had been betrayed and forced to become an outlaw.

Accounts of legendary samurai often crossed over into myth and fantasy, where warriors would battle supernatural creatures and even flee the shores of Japan for heroic exploits in foreign lands. Much of the information about the samurai stems from this peaceful period, where literature, woodblock prints and theatre provide tales often sentimentally told. In modern times, television, movies and video games have contributed to the view of the samurai as stoic and pure-hearted, able to cut down whole armies single-handedly. This anachronistic image is often perpetrated by Hollywood, whose portrayal of the pious, philosophical warrior in The Last Samurai was described by one Japanese reviewer as setting his teeth on edge.

While movie-makers of the West grapple with complex alien cultures, it is the samurais foreignness which gives their history such allure and exotic appeal. On the small islands of Japan, with little outside influence and centuries of isolation, one of the great martial orders of the world rose and fell. This is their history.

THE LEGENDARY SAMURAI

P erhaps the greatest samurai who ever lived was Miyamoto Musashi. He was something of an eccentric he paid little attention to his appearance, was often described as unwashed and was frequently late to his duelling bouts. Musashi was cultivated and accomplished in calligraphy, painting and sculpture, and had killed many men before he had left his teens. He was a swordfighting strategist and dispatched more warriors in duels than any other known samurai, often fighting with sticks, branches and even the oar from a boat. However, his skill with a samurai blade was such that he could split a grain of rice on a mans forehead without drawing blood.

Musashi recorded his accomplishments in The Book of Five Rings , a manual on swordfighting strategy:

I went from province to province duelling with strategists of various schools, and not once failed to win, even though I had as many as sixty encounters. This was between the ages of thirteen and twenty-eight or twenty-nine.

Shinmen Musashi no Kami Fujiwara no Genshin was born in 1584, although he later took the name Miyamoto Musashi after his mothers clan. By the time he was 7 years old, both of his parents had died and Musashi went to be raised and educated by his uncle, Dorin. Musashis first duel was against a travelling samurai called Arima Kihei, who had posted a public notice seeking opponents. Musashi wrote down his name and the challenge was accepted. Dorin was horrified by the news and tried to call off the duel by explaining to Kihei that his nephew was only 13 years old, but Kihei insisted that, for his honour to remain intact, the duel would have to proceed unless Musashi showed up at the scheduled time to prostrate himself. Instead, on the morning of the duel, Dorin arrived to apologise on Musashis behalf. As this was happening, Musashi strode into the hall, grabbed a quarterstaff and charged at Kihei, killing him instantly.

Next page