T HIS WORK IS based on hundreds of interviews in a half-dozen countries over six years; a range of English, Arabic, French, and Turkish publications, news accounts, and social media posts; and my experiences during multiple trips to Saudi Arabia between 2013 and 2018. It is a work of nonfiction, and in no place have I altered names, details, or facts to hide the identities of sources or enhance the narrative. The reader can find citations in the endnotes, as well as supplementary information.

The realities of working as a foreign journalist in Saudi Arabia changed substantially over the course of the events depicted in this bookfirst for the better, then for the worse. In addition to Saudi Arabias treatment of Jamal Khashoggi, the kingdom has imposed travel bans on thousands of Saudis and jailed and prosecuted citizens for expressing themselves online or communicating with foreign journalists. This has led me to err on the side of caution with the identification of Saudi sources, granting many anonymity. I am aware that this affects the transparency of the work, but I prefer that over endangering those who chose to share their stories, thoughts, and information with me.

For the rendering of Arabic names and phrases in English, I have followed no standard rules, but tried to ensure clarity for the nonspecialist reader.

Mohammed bin Salman declined to be interviewed for this book.

INTRODUCTION

B Y THE TIME the young prince who was running the Arab worlds richest country was due to speak, a standing-room-only crowd of international investors, businessmen, millionaires, and billionaires had packed a luxurious hall under massive crystal chandeliers to await his appearance. It was fall 2017, and all had come to Riyadh, the capital of Saudi Arabia, for a lavish investment conference that had unofficially been dubbed Davos in the Desert to give it the same ring of exclusivity and consequence as the annual meet-up of global powerbrokers in the Swiss Alps. This conference, however, had a different goal: to convince the assembled moneymen that the time was now to bet big on Saudi Arabia.

Over the previous days, the kingdom had worked hard to convince its thousands of guests that any preconceptions they had about Saudi Arabia were not true, or were at least on their way to not being true. The country was changing, they were told, opening up and shedding its past as a hyper-conservative, insular Islamic kingdom.

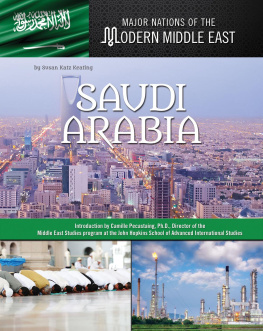

Saudi Arabia had long been known for two things: oil and Islam. The first was pooled in such great quantities under the kingdoms sands that it had turned its royal family, the Al Saud, into one of the worlds richest dynasties, giving the country that bore their name a geo-strategic importance it otherwise would have lacked. The massive oil wealth had shaped the Saudi economy, giving an elite class of princes and businessmen tremendous wealth while most citizens either stayed home or earned salaries from government jobs that paid well and often required little work.

The official Islam of the kingdom was not any Islam, but Wahhabism, the ultraconservative and intolerant interpretation that was woven into the kingdoms history. It taught the faithful to be wary of non-Muslim infidels, saw murderers and drug dealers beheaded in public squares, and deprived women of basic rights. The kingdom was far stricter than most other Islamic societies, but its status as the guardian of Islams holiest sites, in Mecca and Medina, gave it unique clout among the worlds 1.8 billion Muslims.

Saudi leaders knew their kingdoms troubled reputation, so the conference had been carefully planned to challenge how attendees saw the country. Guests had dined on grilled lamb and chocolate truffles at private dinners hosted by princes and officials in opulent homes with swimming pools, art galleries, and hidden liquor cabinets. Women featured prominently in the program and mingled freely with men in the coffee shop of the Ritz-Carlton, with no obligation to cover their hair, as they had to elsewhere.

Slick presentations courted investors for grand initiatives. Saudi Arabia would become a global shipping and transport hub. Entertainment options for its 22 million citizens would proliferate, with amusement parks, cinemas, and concert venues, all of which had long been forbidden for religious reasons. Tourism would boom, with the development of long-neglected historic sites and the creation of a world-class eco-resort in the Red Sea. And in case anyone doubted that the changes were real, the kingdom was finally going to reverse the regulation that had long stood as the primary example of its oppression of women: In June 2018, it would let them drive.

The message was clear: Titanic changes were afoot in Saudi Arabia, and the man driving them was a mysterious, workaholic son of the king, named Mohammed bin Salman. He was 32 years old and out to remake the kingdomand the wider Middle Eastas fast as he could.

Seated in plush chairs or on the tan carpet, the conference attendees had come to take the measure of the young prince. Was he for real? Was he a visionary leader who would drag Saudi Arabia from its conservative past or a rash upstart who would drive it into the ground?

Murmurs raced through the hall as a side door opened, and the prince appeared. He wore the standard outfit for Saudi men: a long white gown with snaps down the front, known as a thobe; a red-and-white-checkered headdress held in place with a black cord; and black sandals. He was chubby, due to his fondness for fast food, and he wore a scruffy beard that climbed high up his cheeks, telegraphing that he was too busy working to waste time on superfluous grooming. Flanked by aides and trailed by photographers and television cameras, he ascended the stage and sank into a white armchair.

He had emerged from obscurity less than three years before, a prince among thousands of princes, who had charmed and plotted his way to the top of the kingdoms power structure. When his elderly father, King Salman, ascended to the throne in 2015, he gave his son oversight of the kingdoms most important portfolios: defense, economy, religion, and oil. Then, shoving aside older relatives, he became the crown prince, putting him next in line to the throne. His father remained the head of state, but it was clear that Prince Mohammed was the hands-on ruler, the kingdoms overseer and CEO.