Published by Kodansha USA, Inc.

All rights reserved.

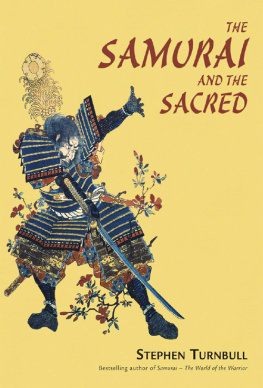

Cover illustration: Utagawa Kunisada I. Samurai with sword in a scene from the fourth act of the Kabuki play Kanadehon Chshingura. Woodblock print. The Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum of Waseda University. Print no. 100-0304.

Rankin, Andrew.

Seppuku : a history of samurai suicide / Andrew Rankin.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Seppuku. 2. Suicide--Japan--History. I. Title.

Authors Note

Japanese names are presented with the family name first, followed by the given name. According to custom, samurai are thereafter identified by their given names. Exceptions are made in a few cases for men of celebrity status whose family names are already familiar.

All translations, from all languages, are my own unless otherwise indicated in the text.

I owe thanks to Professor Karl Friday (University of Georgia), Professor Peter Kornicki (Cambridge), Dr. Mark Morris (Cambridge), and Dr. Dominic Steavu (Heidelberg), each of whom read through a part of the manuscript and made invaluable suggestions for improvement. Cathy Layne, my editor at Kodansha International, did an excellent job of preparing the book for publication and was gentle with her criticisms.

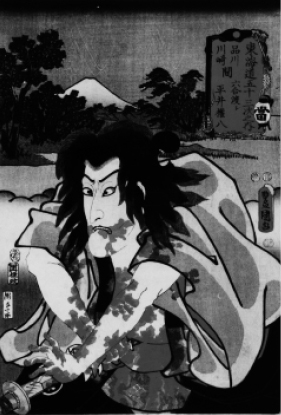

Utagawa Toyokuni III. Seppuku of Hirai Gonpachi (T kaid g j san tsugi no uchi: Hirai Gonpachi), ca. 1830. Woodblock print. The Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum of Waseda University.

Introduction

Aesthetics of Seppuku

Behold! he roared from the castle tower, I am Prince Morinaga, second son of the divine Emperor Go-Daigo, who traces his lineage through ninety-five generations to the sun goddess Amaterasu. My men have run away. Now I shall destroy myself out of contempt for themand you! Watch carefully and you will learn how to cut your bellies, for your day will surely come. He removed his armor and hurled it down from the tower. Now all his enemies could see that he was wearing a princes robes and cloak. As they looked on, he stabbed himself in the stomach, cut cleanly from left to right, and hurled a fistful of his guts against the wall. Dropping to his knees, he inserted the sword into his mouth until the tip of the blade touched his throat. Then he pushed himself forward, and died.

The history of seppukuJapanese ritual suicide by cutting the stomach, sometimes referred to as hara-kirispans a millennium. If the abundant suicides recorded in Japanese war tales are to be believed, the format has been infinitely variable. Defeated warriors slash their stomachs on the battlefield to spite their enemies. There are men who fling their guts into the air or write poems in their own blood. Some disembowel themselves in their rooms and slowly bleed to death. Others are assisted by a comrade or a servant. Whole households commit seppuku together. Friends tearfully dispatch friends. Fathers behead sons, or vice versa. Brothers stab each other. Lovers tear themselves up at the grave of their beloved. Vassals martyr themselves after the death of their lord. Thwarted assassins turn their swords on themselves. Imperialists slit their bowels in the name of the emperor. Wives stab themselves to shame their husbands. Seppuku can be spontaneous or premeditated, voluntary or obligatory, public or private. It can be solemn ceremony or dramatic theater. Samurai cut their stomachs out of honor, shame, desperation, grief, panic, protest, patriotism, narcissism, revenge, hatred, and love. There are descriptions of seppuku performed by warriors, servants, children, bureaucrats, educators, lawmakers, pirates, poets, princes, and priests. Suicide scenes range in scale from mass self-slayings by hundreds of warriors at a time to the death of a lone swordsman on a cliff top. Samurai disembowel themselves on battlefields, atop castle towers, in mountain caves, in grand mansions, in peasant huts, in jail, at roadsides, at temples, in graveyards, on horseback, and at sea. Through all these colorful variations, the essential idea being presented to us does not change: when it is no longer possible to live proudly, the samurai should endeavor to die proudly, and the proudest samurai death is by seppuku.

Origins

As an enduring sociocultural phenomenon, suicide by cutting the stomach has been known only in Japan. The seppuku ritual is unique to Japanese tradition. Yet it cannot have been an aboriginal Japanese practice. For one thing, the sword came late to Japan. The first examples were imported from Korea and China in the third century AD. Prior to that the Japanese islanders hunted with bows and arrows. Early Chinese explorers who visited the Japanese islands recounted the strange ways of the Eastern barbarians. They were a hardworking, hard-drinking people, much given to rituals and summary executions, who ate raw fish and rice, and paid homage to Pimiko, their shaman queen. Aesthetically-minded, the Japanese rendered the foreign swords less functional by thinning the blades, and may initially have used them only as ceremonial objects. A poem by the Japanese emperor Sh mu (701756) acknowledges the superiority of swords made in China, where warrior culture had been thriving for a thousand years. Japans military history cannot be said to begin before the fifth century, when a powerful Japanese force supposedly captured parts of the Korean peninsula. It is in China, not Japan, that we must seek the origins of the swordsman who stabs himself to death.

Chinese warfare was a highly ritualized activity, subject to the constraints of ceremonial laws and divinations. Warriors heading into battle burned offerings to the gods and drank the blood of sacrificial human victims. In victory they decapitated their prisoners and burned the heads before the temple altar. Bloodletting was a noble right. Sacrifice, hunting, and combat were privileges of a military aristocracy. Warfare was less a matter of territorial expansion, more one of aggrandizement. Warriors fought for their ancestors and for their gods. Glory was everything. Not surprisingly, warfare was unending. Chinese histories such as Sima Qians Historical Records (91 BC), which subsequently circulated in Japan, make frequent mention of rebellions, assassinations, massacres, executions, and self-executions. The suicidal strain in Japans martial ethic can be traced to ancient China: to the chariot-borne warlords of the Western Zhou Dynasty (1050771 BC), who consecrated their war drums with sacrificial blood and fell on their swords if the battle went against them, and to charismatic heroes such as the rebel general Xiang Yu, who cut his throat on the bank of the Wu River in 202 BC. Away from the battlefield, suicide was an honorable form of martyrdom. A Chinese text from the third century BC reads, A loyal minister behaves thus: if he can advantage his ruler and profit his state, he will shirk and evade nothing, even killing himself to accompany his ruler in death.

Another factor encouraging suicide was the deadly absolutism of warfare in early China. This was a matter rooted in pragmatism. Rebels who capitulated one year might rise up again the next. Extermination was the key. The sheer size of the Chinese armies demanded drastic measures. A showdown between the Qin and the Zhao at Chanping in 260 BC is believed to have involved more than a million soldiers. After the battle, the Qin made victory permanent by slaughtering prisoners in their hundreds of thousands. Facing inevitable annihilation, vanquished generals were naturally inclined to turn their swords on themselves.