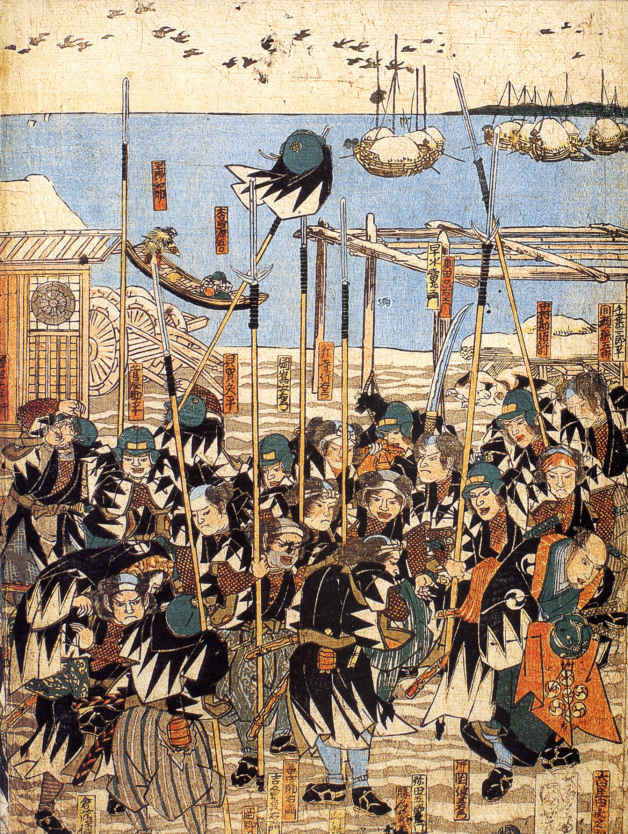

The Forty-Seven Rnin return from their mission.

CONTENTS

The figure approaches from a distance, following the dusty road over the brow of a hill. As he gets closer, he is seen to be a man who is travel-stained and wild, with a sword at his side. He stops, and our eyes meet. Another man is nearby. He too is armed, and he is waiting. The opponents approach each other. There is the flash of a sword blade, and one falls dead.

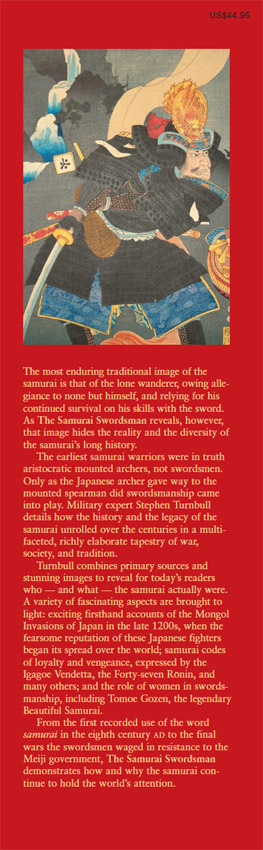

This is the image projected almost daily in Japan by a million television screens, comics, and films. The wanderer is victorious, and he will wander again. He (and it is almost always he, with notable exceptions, discussed in ) is an expert in the martial arts, ruthless and deadly, and always ready for his next encounter. He is the samurai swordsman. The image of this legendary warrior is also fostered in the modern practice of the martial arts of Japan, whose devotees model themselves upon him, seeing themselves as heirs to a great tradition. The martial arts may have been refined and modified in response to changing conditions, but they still enshrine the more subtle and esoteric traditions of the brave samurai swordsman.

In addition to the samurai heritage, the other theme that we will follow throughout these pages is the development of the martial arts themselves. Although the fighting arts of the samurai sword will be emphasized, other techniques of single combat, using bow, spear, and dagger, will be studied to see how their prominence changes through history, and to examine closely how these weapons were actually used in the time when skill meant survival, and failure, death.

This work is a revised version of an earlier book of mine, The Lone Samurai and the Martial Arts, which has been out of print for many years. The text has been thoroughly reworked and augmented by many new illustrations. Much new material has become available since the late 1980s, and a whole new generation of scholars has been producing excellent work from primary sources, which has raised questions about many established notions about samurai warfare. For example, the calling out of pedigrees and the issuing of personal challenges in the heat of battle, often regarded as the stock in trade of the samurai, has been called into question. I also acknowledge the high-quality research into the structure and design of Japanese armor undertaken at the Royal Armouries, Leeds, by Ian Bottomley. I also wish to acknowledge the cooperation of the Maniwa Nen-ry dj and other martial arts institutions in Japan.

Stephen Turnbull

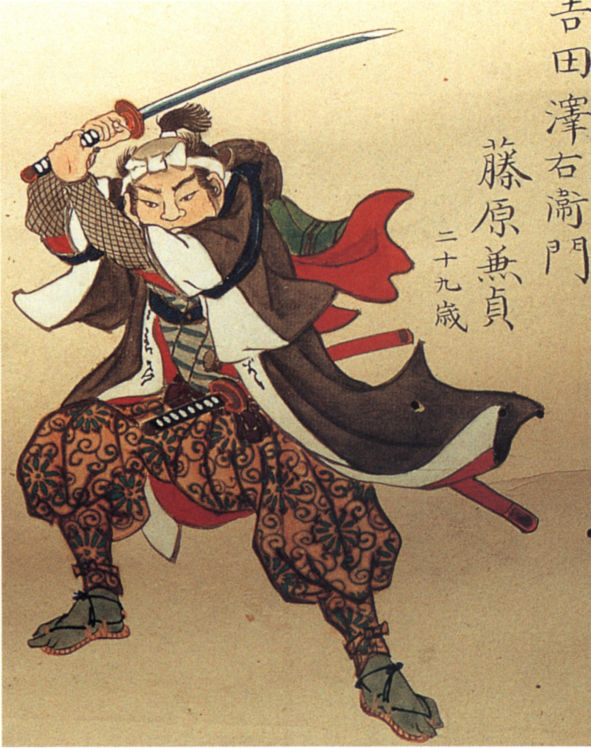

Taira Shigehira, the classic samurai mounted archer.

The most enduring traditional image of the samurai is that of the lone wanderer, owing allegiance to none but himself, and relying for his continued survival on his skills with the sword. This is a powerful picture, and one that has tended to dominate the perception of the archetypal Japanese warrior. However, as the following pages will show, this image owes as much to the peaceful years of the Tokugawa period (16031867) as it does to the preceding years of war. It is also a far cry from the reality of the earliest samurai warriors, who were aristocratic mounted archers rather than swordsmen. These men relied far less on the sword than on the bow. Nor did they hold allegiance only to themselves. Instead, they were part of a vast web of dependent feudal links, with their ultimate loyalty being to the lords who led them into battle. Their fierce sense of pride and personal honor, and their individual prowess at the martial arts, were the only features they had in common with their later popular image. Yet their exploits with horse, bow, and sword set the standard by which future generations of samurai would be judged.

The first use of the word samurai dates back to the eighth century AD, but this was preceded by many centuries of myth, legend, and history. Japans long military tradition, in fact, goes back over two millennia, and at the very beginning of timeaccording to the creation myths that explain the origins of the Japanese islandswe find the image of a weapon. This is the Jewel-spear of Heaven that Izanagi, the father of the kami (deities), plunges into the ocean, and from whose point drips water that coalesces into the land of Japan. Later in the same work (the Kojiki, c. AD 712) we see a reference to the most enduring Japanese martial image of all, when Izanagi uses a sword to kill the fire god, whose birth has led to the death of his wife, Izanami.

Swords also played a part in the stories about the two surviving children of Izanagi: Susano-, the thunder god, and Amaterasu, the goddess of the sun. The Kojiki tells us how Susano- destroyed a monstrous serpent that was terrorizing the people. He began by getting it drunk on sake (rice wine) and then hewed off its heads and tail. But when he reached the tail, his blade struck something it could not penetrate, and Susano- discovered a sword hidden therein. As it was a very fine sword, he presented it to his sister, Amaterasu, and because the serpents tail had been covered in black clouds, the sword was named