Warrior 125

Pirate of the Far East

8111639

Stephen Turnbull Illustrated by Richard Hook

CONTENTS

CAMPAIGN LIFE (1):

THE MECHANICS OF A PIRATE RAID

CAMPAIGN LIFE (2):

DEFENSIVE MEASURES AGAINST PIRATE RAIDS

PIRATE OF THE FAR EAST 8111639

INTRODUCTION: THE WORLD OF THE PIRATE

Raiders and gentlemen

O ver a period of ten centuries the coastal areas of China, Korea and Japan were ravaged by bands of fierce pirates. The name given to them appears in Chinese as wokou, and in Korean it is pronounced waegu. In each case the first character in the two-ideograph word is the ancient name given by the inhabitants of China and Korea to Japan, which shows clearly where they believed that their tormentors had come from. In many cases the identification was correct, and the name entered the Japanese language as wako. But piracy in the Far East was by no means confined to one country of origin, and by the mid-16th century individual pirate bands had acquired a decidedly multinational character. Chinese, Korean and even Portuguese freebooters were involved in massive raids on coastal communities. Some of the most influential pirate leaders were renegade Chinese who based themselves on Japanese islands and sailed from there to terrorize their fellow countrymen under the convenient anonymity of wako with a strong emphasis on the character Wa. That is why the present work is called Pirate of the Far East and not simply Pirate of Japan.

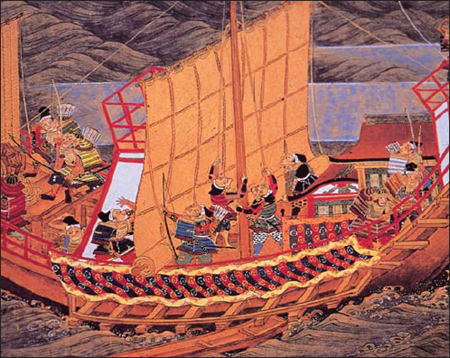

A painting in the National Military Museum, Beijing, depicting a battle between Chinese troops and wako. One Chinese soldier holds a sharpened bamboo branch, showing that he is a member of Qi Jiguangs mandarin duck formation.

The first use of the expression wokou to refer to raiders from the country of Wa appears on a stone tablet erected in AD 414 in southern Manchuria to the memory of the hero King Gwanggaeto of the Goguryeo state of Korea. This was a time when there was considerable military involvement between Japan and Koreas three kingdoms of Baekje, Silla and Goguryeo. Troops frequently came from Japan to fight on the Korean peninsula, and the use of wokou on the monument probably refers to Baekjes willing use of Japanese troops in its wars against Goguryeo rather than pirate raids in the later meaning of the term. Several centuries had to pass before the word wako was to become associated with ongoing raids arising from uncontrolled aggression that was usually and casually attributed to Japan.

Indeed at that time the prevailing image held by the inhabitants of continental East Asia of the Japanese was a positive one. Japanese armies frequently fought in Korea as the allies of the Baekje kingdom, on whose behalf they suffered a heavy defeat at the battle of the Baekcheon river in 663. Otherwise the only Japanese visitors to China and Korea were cultivated diplomats, earnest students, or disciplined Buddhist monks in search of truth. In 719 the arrival of a group of envoys from Japan to China occasioned the comment that Japan was a country of gentlemen, where the people are prosperous and happy and etiquette is carefully observed.

During the ninth century, in fact, the Japanese tended to be the victims of piracy, not its perpetrators. In 811, 813, 893 and 894 Korean pirates took advantage of the turmoil caused by the break-up of the Unified Silla Kingdom to raid Japan, but eventually suffered heavy casualties and withdrew. Japanese pirates did exist, but their activities were confined to domestic targets. These were the days when the emperors of Japan were beginning to hire local landowners with military skills the first samurai to guard the palace in the capital city of Nara and to protect them against rebels and evildoers. The early samurai were frequently called upon to quell pirate raids, either from Korea or from their fellow countrymen. The perpetrators of these domestic outrages were not called wako; there was no confusion over their native origin. Instead they are referred to as kaizoku, which literally means sea robbers and became the generic term for Japanese pirates operating within Japan.

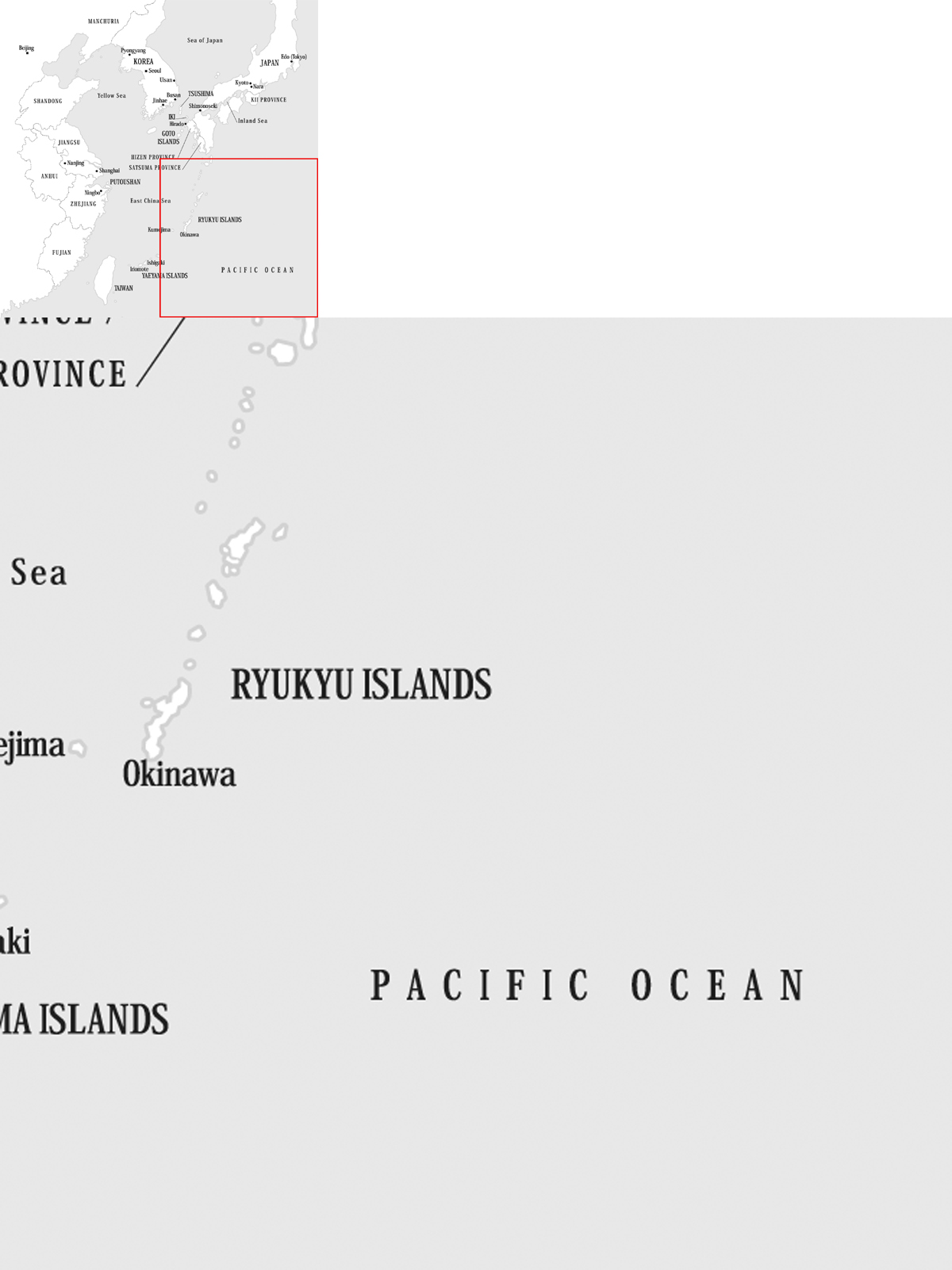

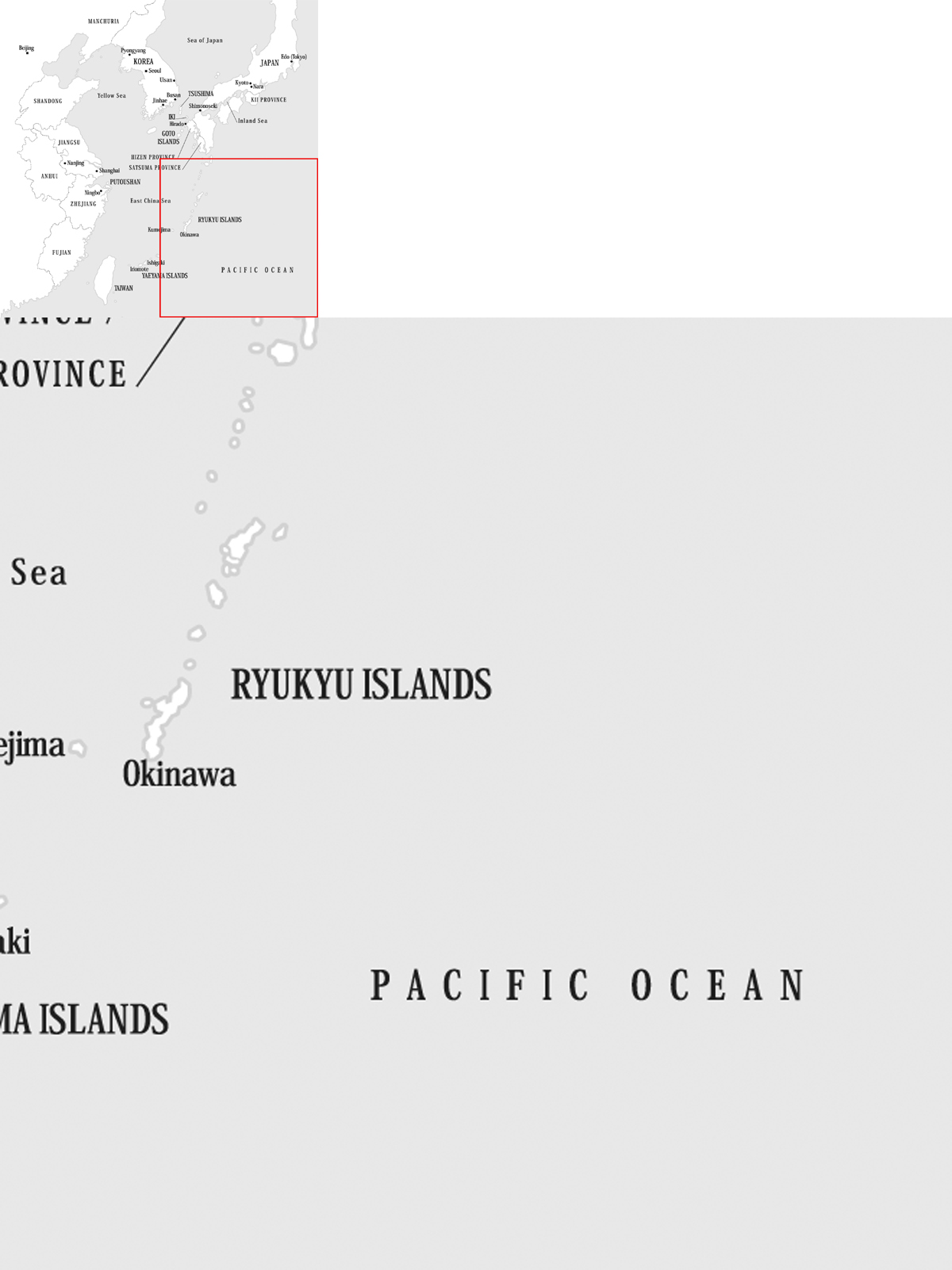

Map of China, Japan, Korea and the Ryukyu Islands, showing the main sea areas in which pirates operated.

In 862 an imperial court history noted that pirates in the west of Japan were boldly seizing property, attacking the boats carrying tax rice and committing murder, so orders were sent for their pursuit and apprehension in the provinces along the Inland Sea. This stretch of water lies between Japans three main islands of Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu and was well suited to illegal seafaring. Hundreds of islands and secluded coves provided shelter for any local fisherman who sought to augment his honest income by preying on the seaborne trade that passed through the narrow straits of Shimonoseki at the Inland Seas western extremity on its way to China and Korea. Rich pickings could also be had at its eastern end, where lay the imperial heartlands around Nara and Kyoto, the city that was to become the new capital in 894. In 867 we read of pirates gathering in the strategically located Iyo province on the northern coast of Shikoku to go plundering along the Inland Sea, while other bands operated along the coasts of the Sea of Japan and round the Kii peninsula. In 1114 the Chief Priest of Kumano was commissioned to use his warrior monks to pursue and capture the pirates who infested the coastline of Kii province.

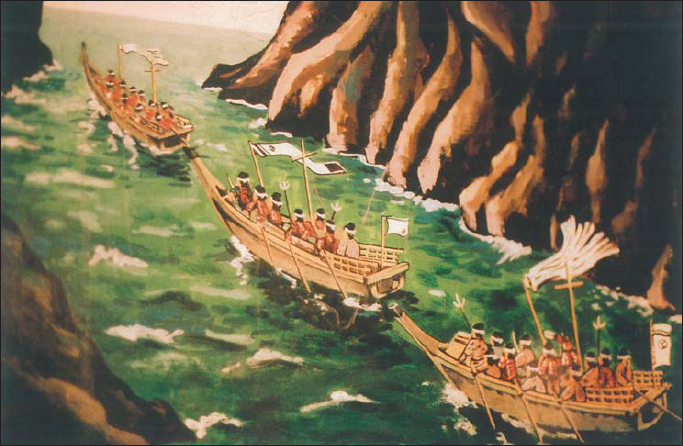

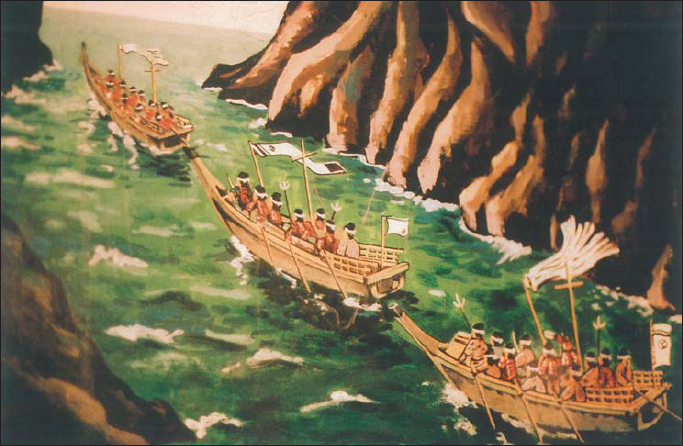

The Kumano pirate fleet sail out from their cave refuge below the cliffs of Sandanbeki at Shirahama, from a painting hanging in the pirate cave.

The early pirates tended to operate in small groups, and some had links to Korea. They could be bold in their exploits, and in 931 the Court issued orders to guard the roads and rivers that led from Kyoto to the Inland Sea; but little seems to have been achieved because similar orders had to be issued in 932 and 933. The 932 order included the grand-sounding appointment of a tsuibu kaizoku shi (envoy for the pursuit and capture of pirates), but he must have been ineffective because in 934 an official granary in Iyo province was attacked and burned. Two years later Iyo was to provide Japan with its first pirate king: Fujiwara Sumitomo, whose insurrection is described later.

Samurai versus pirates

The next pirates that the Japanese had to contend with were Jurchens from Manchuria, who were used to raiding Korea. In 1019 Jurchen pirates attacked the Japanese islands of Tsushima and Iki and various areas on the mainland, carrying off hundreds of captives. Their returning fleet was intercepted by Korean ships, and eight Jurchen vessels were captured. The sympathetic Koreans returned 259 Japanese captives to their homes.

Next page