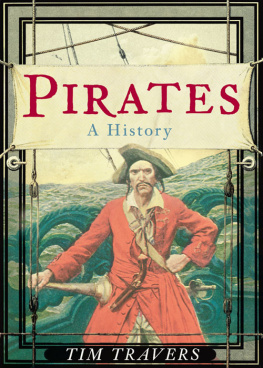

Cover illustrations: (front) Captain Kent the romantic image of a pirate aptain, as imagined by Howard Pyle, the American illustrator, who did more than any other individual to imprint on the modern mind what a pirate looked like. Authors collection; (spine) skull and cross bones taken from a Howard Pyle illustration. Authors collection; (back) a version of the Jolly Roger flag, c. 1704. Courtesy of Joel Baer.

Contents

Any attempt to write a history of piracy must gratefully rely on numerous authors and selected archives. These are listed in the bibliography, but special thanks are due to the librarians and archivists of the British Library, London; the Public Record Office, Kew; and the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. Valuable, too, was the inter library loan office at the University of Victoria, as were the students of my pirate history seminar at the University of Victoria. Many thanks are also due to those who generously supplied lodging and hospitality in England, especially Patricia Rogers, and Jo and Charles Cumberlege. Others who kindly helped along the way with information and encouragement include Chris Archer, Peter Fothergill-Payne, Richard Unger, and Patrick Wright. Thanks also to Jonathan Reeve, publisher, for his patience as the manuscript went over the time limit. Most of all, Heather gave up much of her time to solve all computer problems, and thanks to her, the manuscript and the author both survived. Of course, all errors are due to the author alone.

1

The golden age of piracy in the West lasted from the 1680s to the 1720s, and during this time some 5,000 pirates roamed the seas. Who were these pirates? A great many were sailors who became unemployed after major European wars ended. Others came from the hard grind and exploitation of the Newfoundland fishery. Still other pirate recruits came from ships that pirates captured, and whose crews either volunteered or were forced to join. This was especially the case with captured slave ships, where conditions for the crew, let alone the miserable slaves, were brutal. And many African slaves also joined as willing or unwilling pirates. Then there were indentured servants from the colonies who found their lives unendurable and were happy to try piracy. Many individuals went on account as pirates simply to improve their lot in life, and others were attracted by the promise of wealth that could not be obtained in any other way. Some perhaps joined pirate crews for political or ideological reasons, and democracy did generally rule on pirate ships. Merchant and navy ships were notorious for poor conditions and bad treatment, and so sailors from these ships often decided to try their luck with pirate ships. In fact, mutinies on merchant ships in particular were often caused by lack of provisions and tardiness in paying their crews, so that most of the crew would turn pirate. Altogether there were many reasons to become a pirate at this time, and there was always the lure of treasure to attract men unhappy with low wages and poverty stricken lives.

How then to enter the world of the pirates of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries? One way is to listen to what they said about themselves. A good start is an early eighteenth-century mock trial, in which a group of pirates pretended to put themselves in court in order to both criticize and make fun of the judicial system of the day:

Attorn. Gen: Ant please your Lordship, and you Gentlemen of the Jury, here is a Fellow before you that is a sad Dog, a sad sad Dog; & I humbly hope your Lordship will order him to be hanged out of the Way immediately. He has committed Pyracy upon the High Seas, and we shall prove, ant please your Lordship, that this Fellow, this sad Dog before you, has escaped a thousand Storms, nay, has got safe ashore when the Ship has been cast away, which was a certain Sign he was not born to be drownd; yet not having the Fear of hanging before his Eyes, he went on robbing & ravishing, Man, Woman and Child, plundering Ships Cargoes fore and aft, burning and sinking Ship, Bark and Boat, as if the Devil had been in him. But that is not all, my Lord, he has committed worse Villanies than all these, for we shall prove, that he has been guilty of drinking Small-Beer; and your Lordship knows, there never was a sober Fellow but what was a Rogue. My Lord, I should have spoken much finer than I do now, but that, as your Lordship knows our Rum is all out, and how should a Man speak good Law that has not drunk a Dram. However, I hope your Lordship will order the Fellow to be hangd.

Judge: Hearkee me sirrah, you lousy, pitiful, ill-lookd Dog; what have you to say why you should not be tuckd up immediately, and set a Sundrying like a Scare-crow? Are you guilty or not guilty?

Pris[oner]: Not guilty, ant please your Worship.

This mock trial gives an insight into the humour, as well as the fears, of the pirates. This skit was performed on an island off Cuba in 1722 by a pirate crew commanded by Captain Anstis, and recorded by Captain Charles Johnson, the eighteenth-century historian of piracy. The pirates well knew that they had committed or were about to commit crimes that would result in the hanging of many of them, or at the least produce an untimely death of some kind. So this mock trial was a way of getting over their fear of hanging by making fun of it, and at the same time showing a defiance of the law in pursuing their piratical ways regardless.

Captain Charles Johnsons book is one of the key sources for Western piracy in the Golden Age of piracy from the 1680s to the 1720s. Entitled A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, it was first published in 1724, and subsequently in several further editions. Unfortunately, no one knows who Captain Charles Johnson was, since this name was a pseudonym, although some older authorities consider Johnson might have been the author Daniel Defoe. Some wonder if Johnson was the playwright Charles Johnson (16791748), who did write a play called The Successful Pirate, while still others consider that Johnson must have been a sailor or even a pirate, judging from his inside knowledge of the sea and his connections to many pirates. Whoever he was, Johnsons book contains biographies of many of the most famous pirates of the day such as Avery (or Every), Blackbeard (or Teach), Rackam, Roberts, Kidd, and the two female pirates, Mary Read and Anne Bonny. By cross checking with documents from the English High Court of the Admiralty, Colonial Office records, trial reports, and other official sources, it seems that Johnson was generally quite accurate, although details were sometimes wrong, and speeches were probably mostly invented.

The world of the pirates has been explored in a large number of books, but the present volume tries to extend the time and space of piracy by going back to classical and medieval piracy and forward to modern piracy, while also widening the search to include Asian and South Asian piracy. Yet the greatest volume of archival and other resources easily available relates to the period from about 1600 onward in regard to Caribbean, Atlantic and Pacific piracy, and so a number of chapters deal with this area. First hand accounts of this period are particularly useful, and some are to be found in the British Library, London. Yet our modern image of the pirate is very strongly formed not from archives or from modern books, but by one or two late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century childrens books, by the lurid illustrations of the American Howard Pyle at the turn of the century, and by the cinema.

Next page