CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

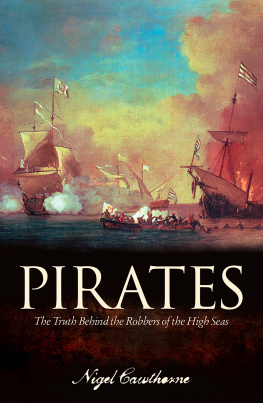

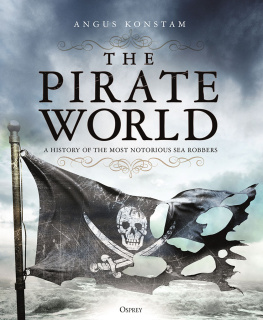

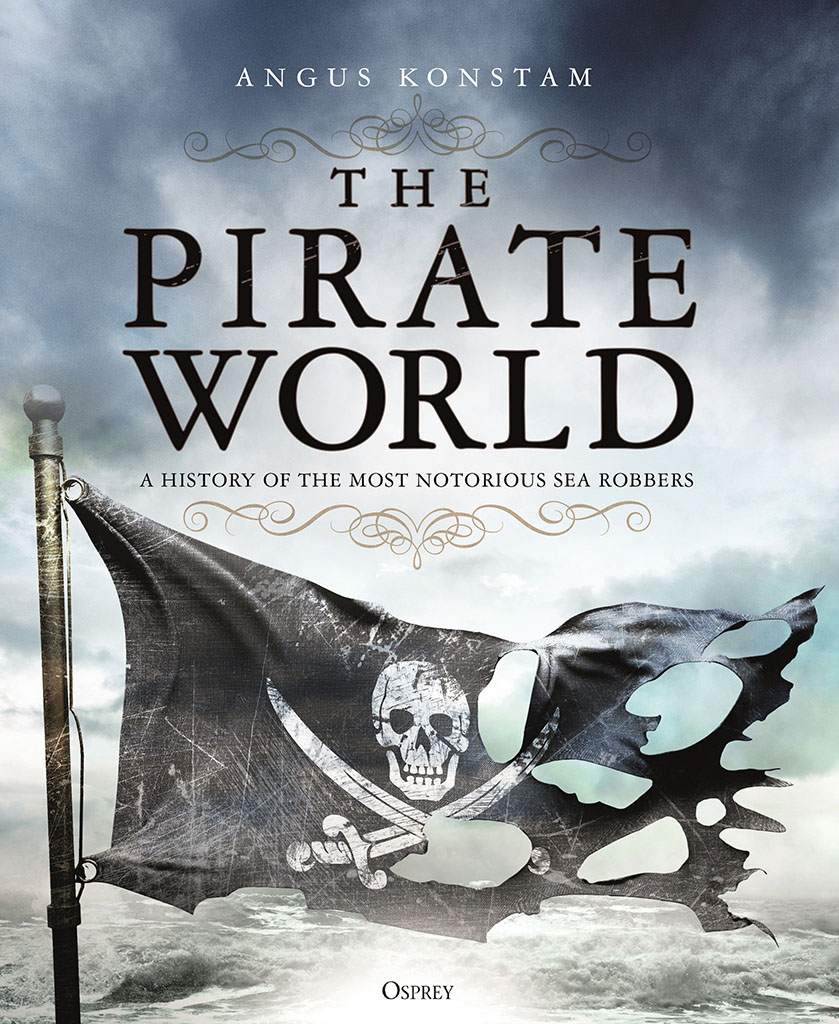

Crime, and the publics fascination with it, are as old as civilization itself. So, it wasnt surprising that in 1724, when a London publisher produced a book called A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, this lurid pirate expos became a best-seller. It lifted the lid on a world of violent criminals operating on the high seas. It told of men (and a few women) who rebelled against society, and who lived by their own piratical code. Of course it also helped that most pirates met a colourfully violent end. Three centuries later the fascination with them still remains.

For most people the word pirate conjures up an image of a slightly comical seaborne ruffian with a parrot, a peg leg and a bandana. This comes from a century or more of cartoonish depictions of pirates in Peter Pan, Treasure Island and The Pirates of the Caribbean. Nowadays these sanitized pirates are used to sell everything from rum to home insurance. Similarly, like the pirate himself, his skull and crossbones motif has become an instantly recognizable symbol whose meaning is far removed from its dark and sinister origins.

In fact, all this began long before Treasure Island, with Captain Charles Johnson, the author who wrote that bestseller back in 1724. His descriptions of Blackbeard and Black Bart Roberts, of Calico Jack Rackam and Charles Vane, captured the public imagination, and have ensured that his book is still in print almost three centuries later.

His pirates, though, were real people. Nowadays, fictional pirates are usually portrayed either as romantic characters, or as figures of fun. Even historians have added to the problem by using a term that conjures up romance rather than the grim reality of robbery on the high seas. The phrase the Golden Age of Piracy was first coined by the creators of pirate fiction rather than by people who experienced piracy for themselves. There was nothing golden or romantic about the real thing. Still, the term serves as a useful historical shorthand for a time when some of the best-known pirates in history were sailing the worlds oceans in search of prey.

Even the term pirate has been changed over the years. Scriptwriters continually manage to confuse the name with others, such as privateer, buccaneer, filibuster, corsair, freebooter and swashbuckler. All of them have their own separate meanings. A privateer was a government-sanctioned pirate who did not attack his own people. The French called these people corsairs, although even this term became associated with Mediterranean pirates instead of privateers. A buccaneer was a 17th-century raider who preyed on the Spanish in the Caribbean, while a filibuster (or freebooter) was simply a French word for a buccaneer. As for swashbuckler, the term meant a 16th-century brigand, or a 17th-century swordsman, but in the 20th century it was adopted by the writers of pirate fiction, and then by Hollywood. In the piratical heyday most of these terms were never used the way they are today. Finally, there were pirates. The dictionary specifies that a pirate is someone who robs from others at sea, and who acts beyond the law. Usually, they attacked whatever ships they came across, regardless of nationality. So that term at least should be pretty clear.

Sometimes, though, these pirates themselves crossed the line from one category to another. For example, Captain Kidd was a privateer who later turned to piracy. Francis Drake was a privateer, although the Spanish simply called him a pirate. To muddy the waters further, Henry Morgan was a buccaneer operating as an English privateer, although technically much of the time he acted as a pirate! While this all sounds pretty confusing nowadays, in fact for most seafarers from the past it all made perfect sense. One of my tasks in this book is to unravel it all, and explain just what piracy actually meant.

This book gives you a window into this piratical past. In these pages well cover the whole history of piracy, from the time of the Egyptian pharaohs to the present day. However, well be concentrating mostly on the real heyday of piracy. This falls neatly into two halves. The first is the colourful era of the 17th-century buccaneers who preyed on the Spanish Main men like Henry Morgan or the bloodthirsty Franois LOlonnais. The second is what well reluctantly call the Golden Age of Piracy. This was the brief but heady period in the early 18th century when the likes of Blackbeard, Black Bart and Charles Vane roamed the seas. So, while giving you an overall picture of piracy through the ages, well also look more deeply at these two key periods, and explain why piracy was so prevalent back then.

The main aim of this book is to strip away the myths and inventions from these historical figures to reveal the brutal but utterly fascinating world of piracy as it really was. This book tells the story of the real pirates of history the men for whom shipwreck, starvation, disease and violent death were a constant threat, and whose careers were usually measured in months rather than years. The notion that their lives were in any way romantic would have been hugely amusing to them.

Angus Konstam

Edinburgh, 2018

Chapter One

PIRATES OF THE ANCIENT WORLD

This colourful modern mural celebrates the capture of the young Julius Caesar by Cilician pirates in 75 BC. They held him hostage for just over a month, until his ransom was negotiated. Once freed, Caesar gathered a Roman punitive force together, captured the pirates in their island lair, and had them crucified. (DEA PICTURE LIBRARY/Getty Images)

THE SEA PEOPLES

Piracy has probably been around since man first took to the sea. However, it first appeared in the historical records before the building of the Egyptian pyramids. As in any period, piracy in the ancient world flourished when there was a lack of central control, and in areas beyond the reach of major powers. The first known pirate group was the Lukkans, a group of sea raiders based on the south-eastern coast of Asia Minor (now modern Turkey). In the 14th century BC, Egyptian scribes recorded that they raided Cyprus, then allied themselves with Egypts rivals, the Hittites. A century later the Lukkans drop from the records, their disappearance linked to the emergence of a new maritime threat. It is now believed that these pirates became assimilated into a confederation of maritime nomads known as the sea peoples.

Historians have blamed these sea raiders for the collapse of the Bronze Age cultures of the eastern Mediterranean, the end of the Mycenaean Greek civilization, and the destruction of the Hittite Empire. It seems that only the Egyptians weathered this storm. The term sea peoples was first coined by Egyptian chroniclers, who claimed the invaders were migrating tribes who originated in the Aegean and Adriatic. These nomads raided and fought, but they also traded, developing sea routes that spanned the eastern Mediterranean. The same sources mention that the sea peoples were divided into several tribes the Shardana, Denyen, Peleset, Shekelesh, Weshesh and Tjeker. Later historians added two more the Tursha and Lycians (or Lukkans). The Shardana, Shekelesh and Peleset tribes may have originated in the northern Adriatic, but the Shardana have also been linked to Sardinia. Others probably came from Anatolia. Whatever their origins, these sea raiders formed the first known pirate confederation in history.