BLACKBEARDS LAST FIGHT

Pirate Hunting in North Carolina 1718

ANGUS KONSTAM

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

These days, pirates are generally regarded as larger-than-life caricatures people who exist more in the pages of fiction or the cinema screen than in the historical past. Like gunfighters of the Wild West or Arthurian warriors they are usually seen as semi-fictional creatures, whose real exploits have been submerged in a tidal wave of myth and fictional make-believe. Despite the recent upsurge of piracy in East African waters, piracy has largely become divorced from the harsh realities which once surrounded it, or which still do today.

To the seafarers of the early 18th century piracy was no fantasy. It was a brutal and very real threat to their lives and livelihood. To sail through the pirate-infested waters of the American Atlantic seaboard or the Caribbean was to risk an encounter with pirates who bore no resemblance to our modern caricature of them. These people would kill indiscriminately, torture for amusement, and rob for their own gratification. If the seaman was lucky he would escape with his life. Others were not so fortunate.

Of course, piracy wasnt a new phenomenon. It had existed since ancient times even Julius Caesar had an encounter with pirates some 1,800 years before Blackbeard was first heard of. Piracy was a cyclical curse it thrived in areas where there was little central authority or effective naval presence, and it was generally suppressed through the imposition of law, and by aggressive naval patrolling. The decade from 1714 to 1724 saw one of these dramatic increases.

Pirates established themselves in the Bahamas, and ranged as far afield as Newfoundland and the coast of Brazil, attacking merchant ships, and largely evading capture. It took a concerted effort to quell this tide of crime, but by 1718 it looked as though it was largely under control. Only a few pirate crews remained at large. One of them was led by Edward Teach better known as Blackbeard. He was only one of many pirates who operated in these waters during this period an age known as The Golden Age of Piracy. Others included Bartholomew Roberts (Black Bart), Charles Vane, Calico Jack Rackam, Gentleman Stede Bonnet, Black Sam Bellamy, and the two women pirates Anne Bonny and Mary Read. Despite their exploits, most of these pirates are now half-forgotten. By contrast Blackbeard still remains a household name. Others were more brutal, or captured more ships, or had longer piratical careers. It was Blackbeard, however, who became the most notorious pirate of his day, and who remains so some three centuries after his death.

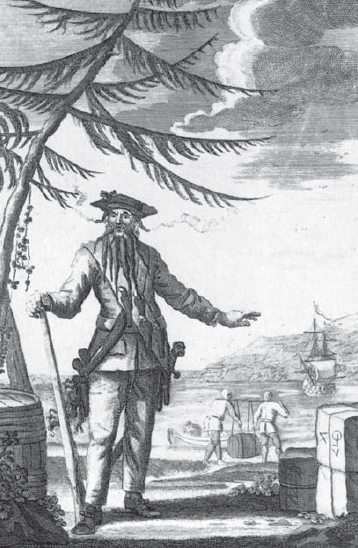

There are three main reasons for this. First of all, Blackbeard looked the part. He cultivated a sinister appearance to intimidate his victims, and this made him a larger-than-life character even while he was still alive. Secondly, his exploits formed the core of a biography of pirates, published just eight years after his death. He quickly became the archetypal pirate of the Golden Age. Finally, in 1718 he almost single-handedly brought merchant trade to a halt in colonial North America. His blockade of Charleston caused such widespread alarm that he became the 18th-century equivalent of Public Enemy Number One.

More than anything this attack against the main port of the South Carolina colony made Blackbeard the most feared pirate in American waters. The fragile economies of the American colonies relied extensively on maritime trade, and Blackbeard posed such a serious threat to this economic lifeline that action had to be taken. This, though, occurred at the time of a royal initiative to pardon pirates who turned themselves in, in the belief that this would reduce the scale of the problem. While the policy worked, it also meant that Blackbeard remained a threat, whether he was actively cruising for prey or not.

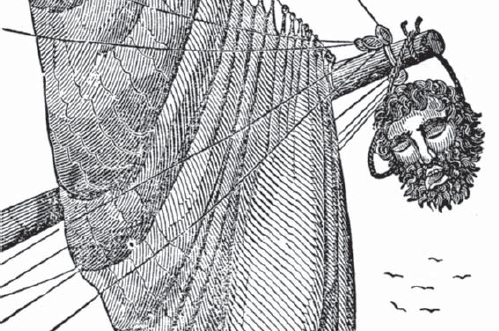

According to his first biographer, Captain Johnson, Edward Teach was known as Blackbeard from the hair, which, like a frightful meteor, covered his whole face, and frightened America more than any comet that had appeared there a long time.

While most colonial governors limited their response to complaining to London and demanding naval protection, Governor Alexander Spotswood of Virginia was a man of action, who decided to take matters into his own hands. Even though Blackbeard was officially a pardoned criminal, and resident in a neighbouring colony, Spotswood decided to attack the pirate in his own lair, and so remove the threat he posed once and for all.

Therefore the scene was set for what would become the most successful anti-piracy raid of the entire Golden Age of Piracy. What unfolded was a drama worthy of a Hollywood film, only one with a real piratical cast, and which actually happened. Just over 300 years ago, the most notorious pirate in history met his match.

ORIGINS

The making of Blackbeard

The story of Blackbeard really begins with a peace treaty, and a fleet of Spanish treasure ships. The signing of this treaty and the wrecking of the Spanish treasure fleet took place within two years of each other, and the two events conspired to produce a wave of crime that threatened to cripple the fragile economy of the American colonies. Today this wave of criminal activity is often referred to as The Golden Age of Piracy. To the victims of pirates such as Blackbeard there was nothing golden about it.

The signing of the Peace of Utrecht in April 1713 marked the end of the fighting between France, Spain, Great Britain, Portugal and Holland in the War of the Spanish Succession (170114). While the war between France and Austria dragged on for another year, the conflict between Europes principal maritime powers was now over. For more than a decade the Caribbean basin had been a theatre of war, and privateers of all these nations had sailed its waters, preying on the merchant shipping of their nations enemies. When news of the peace treaty reached the Americas that June, all these lucrative privateering contracts were rendered null and void. Thousands of well-armed seamen found themselves out of work, and many were unwilling to return to their previous mundane and poorly paid employment as merchant seamen. Privateering had given them a taste for plunder.

Effectively privateering was nothing more than state-sponsored piracy. When a war began a sea captain or ship owner could apply to his government for a letter of marque. The aspiring privateer agreed to attack the merchant shipping of his countrys enemies, and to take the prizes into a friendly port where the ship and cargo would be sold. This was all perfectly legal in time of war. In return the government got a share of the proceeds the level was usually set at 10 per cent. Obviously this was an extremely lucrative arrangement for everyone except the foreign ship owners, and of course foreign governments were doing exactly the same thing. It has been estimated that during the War of the Spanish Succession more than 300 privateers of various nationalities were operating in American waters, from Newfoundland down to Brazil. Most based themselves in the Caribbean, where the trade in rum, sugar and slaves ensured there was no shortage of prizes.