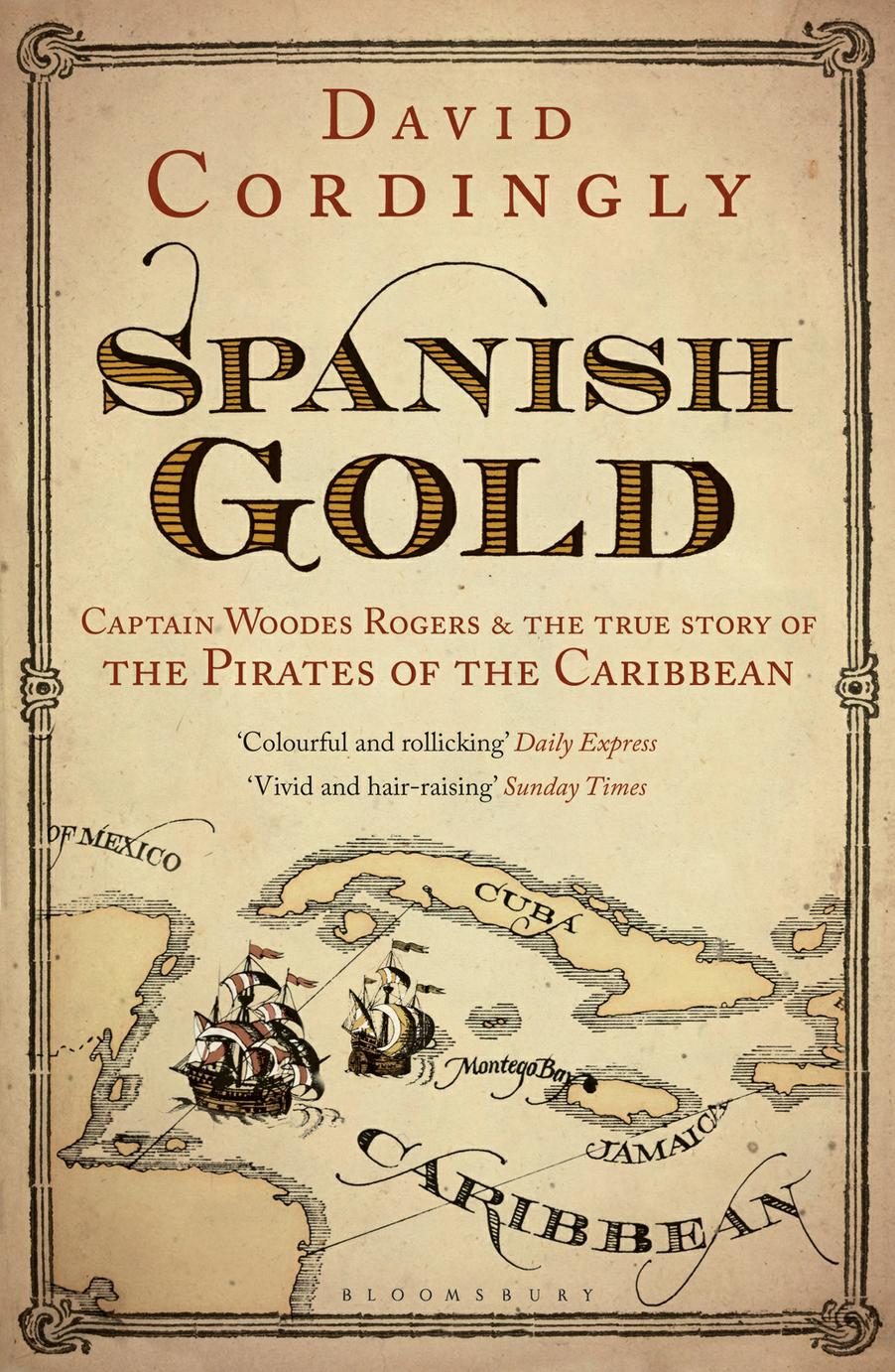

SPANISH GOLD

Captain Woodes Rogers and

The True Story of the Pirates of the Caribbean

David Cordingly

For Shirley

Contents

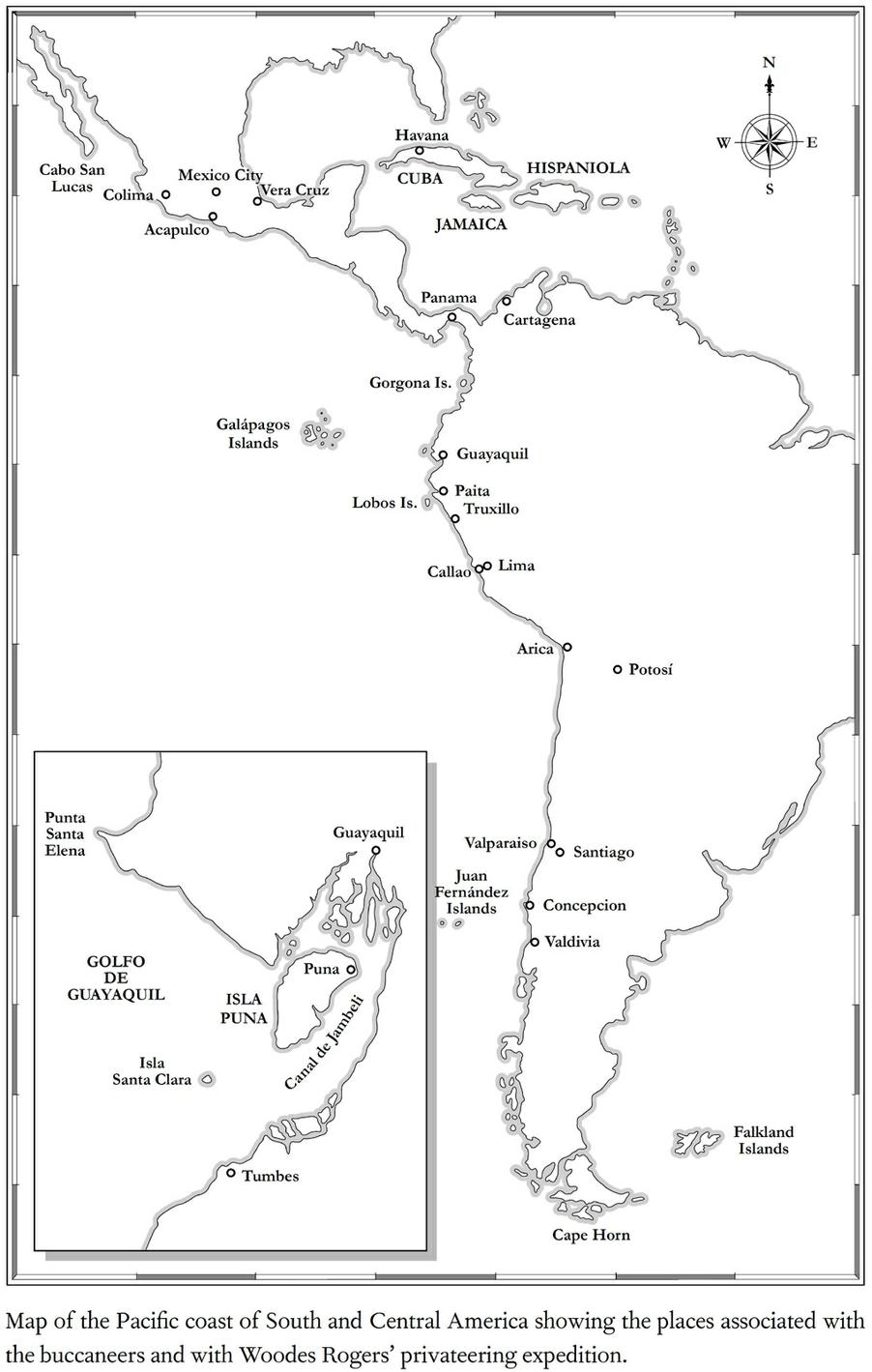

The Juan Fernndez Archipelago consists of three islands and a rocky islet. The largest island, which used to be known as Isla Ms a Tierra, is the only one which has ever been inhabited and is the one which the buccaneers and later seafarers called Juan Fernndez. In 1966 the Chilean government renamed this island Isla Robinson Crusoe, and the smaller uninhabited island 112 miles to the west (formerly called Isla Ms Afuera) was renamed Isla Alejandro Selkirk. The third island in the group was, and still is, called Isla Santa Clara, and the rocky islet is called Islote Juananga. I have followed the usage of the early seafarers and always refer to the large island by its original name, as in this quote from Woodes Rogers journal, At seven this morning we made the Island of Juan Fernandez.

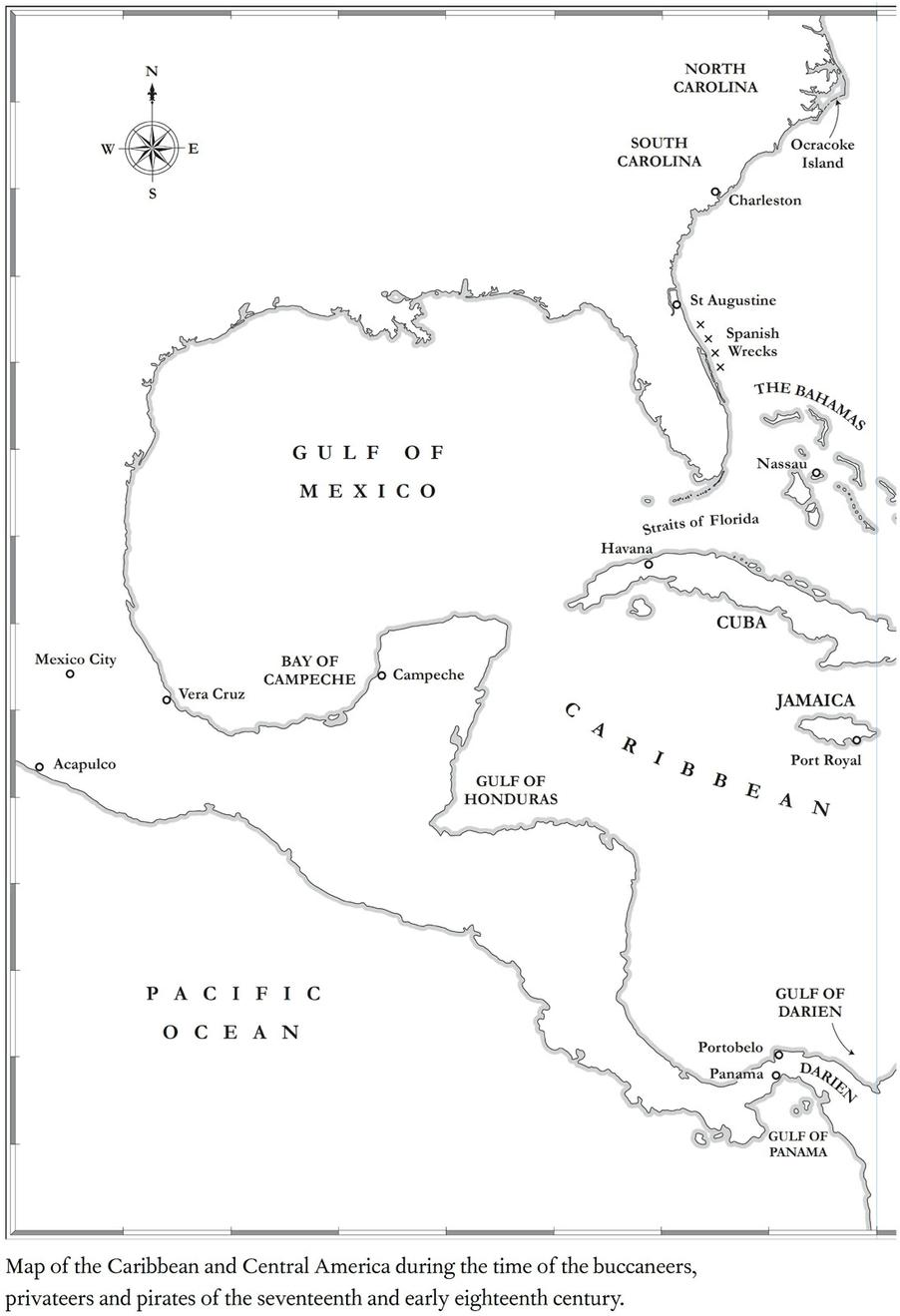

During the course of this book I have used the terms pieces of eight, pesos and Spanish dollars depending on the source of the information. All three terms apply to the same silver coin which was worth eight reales and was the common currency used throughout Spains empire in the New World for more than three centuries. One side of the coin had the Spanish coat of arms and the other side usually had a design which included the pillars of Hercules. The twin pillars symbolised the limits of the ancient world at the Straits of Gibraltar and these eventually formed the basis of the dollar sign used today. In 1644 one piece of eight (or peso or Spanish dollar) was valued in England at four shillings and sixpence. That would be the equivalent of about 18 or US $28 today.

In their books Woodes Rogers and Edward Cooke usually anglicised the names of the Spanish ships which they encountered. I have used the Spanish names for Spanish ships and smaller vessels. However, I have retained the archaic spelling of Dutchess and Marquiss for the English ships because these are the names given to them by the privateers.

In the autumn of 1717 the following item appeared in a London newspaper: On Wednesday Capt Rogers, who took the Aquapulca Ship in the South-Seas, kissed his Majestys hand at Hampton Court, on his being made Governor of the Island of Providence in the West Indies, now in the possession of the Pirates.

Behind this brief statement lies an extraordinary story. It is the story of a tough and resolute sea captain who led a privateering raid on Spanish ships in the Pacific, rescued a castaway from a deserted island and then played a key role in the fight against the pirates of the Caribbean. It is also a tale of treasure ships and treasure ports, of maroonings and hangings, and the genesis of Daniel Defoes most famous book, The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe . The story is played out against the background of fierce colonial rivalry between Britain, France and Spain; and it is linked with the fabulously rich trade in gold and silver from Central and South America, the trade in silks and spices from the Far East and the shipment of black slaves from the west coast of Africa to the sugar plantations of the West Indies. Many of the events centre on two groups of islands: the Bahamas and the remote archipelago of Juan Fernndez in the South Pacific.

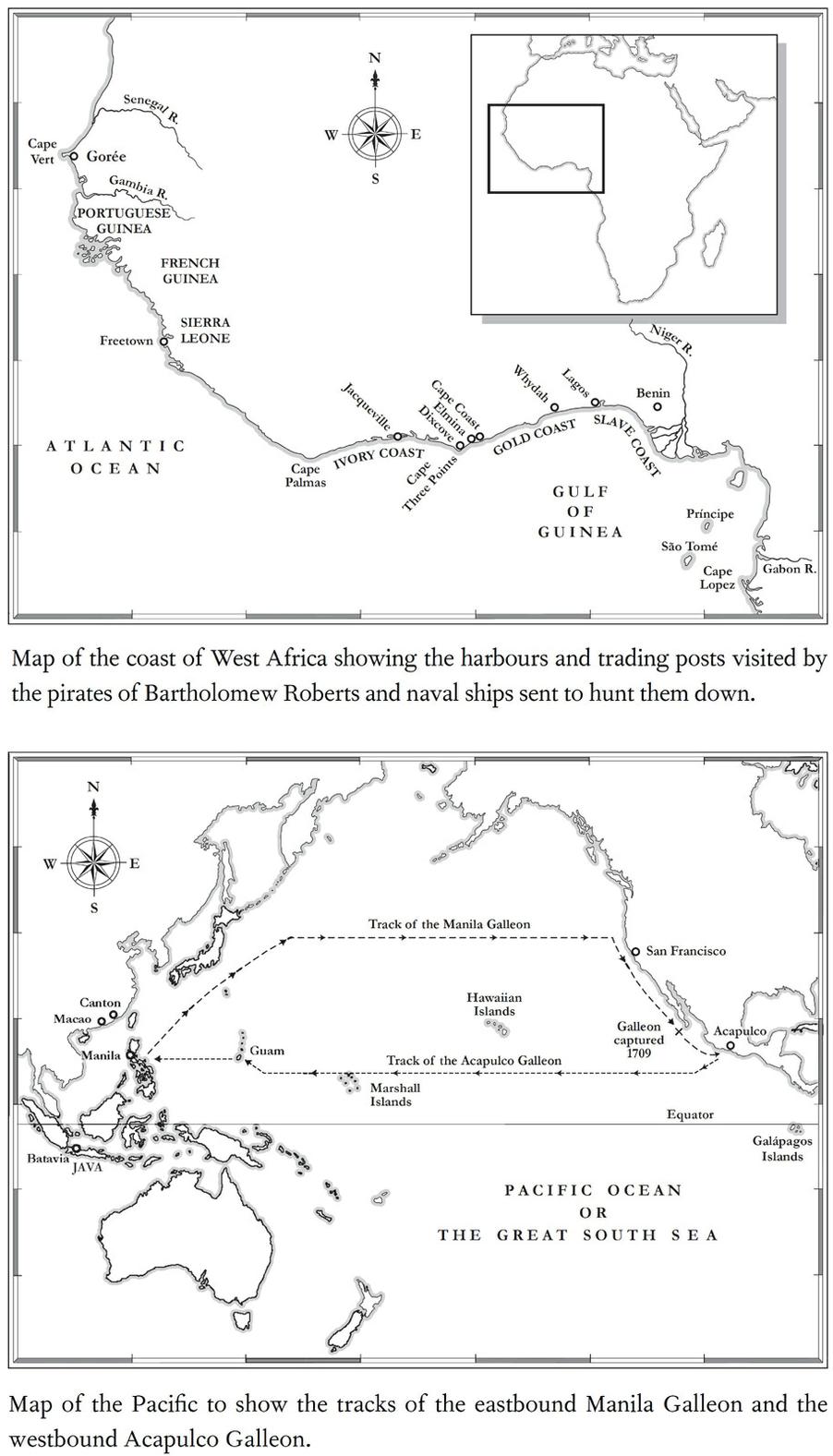

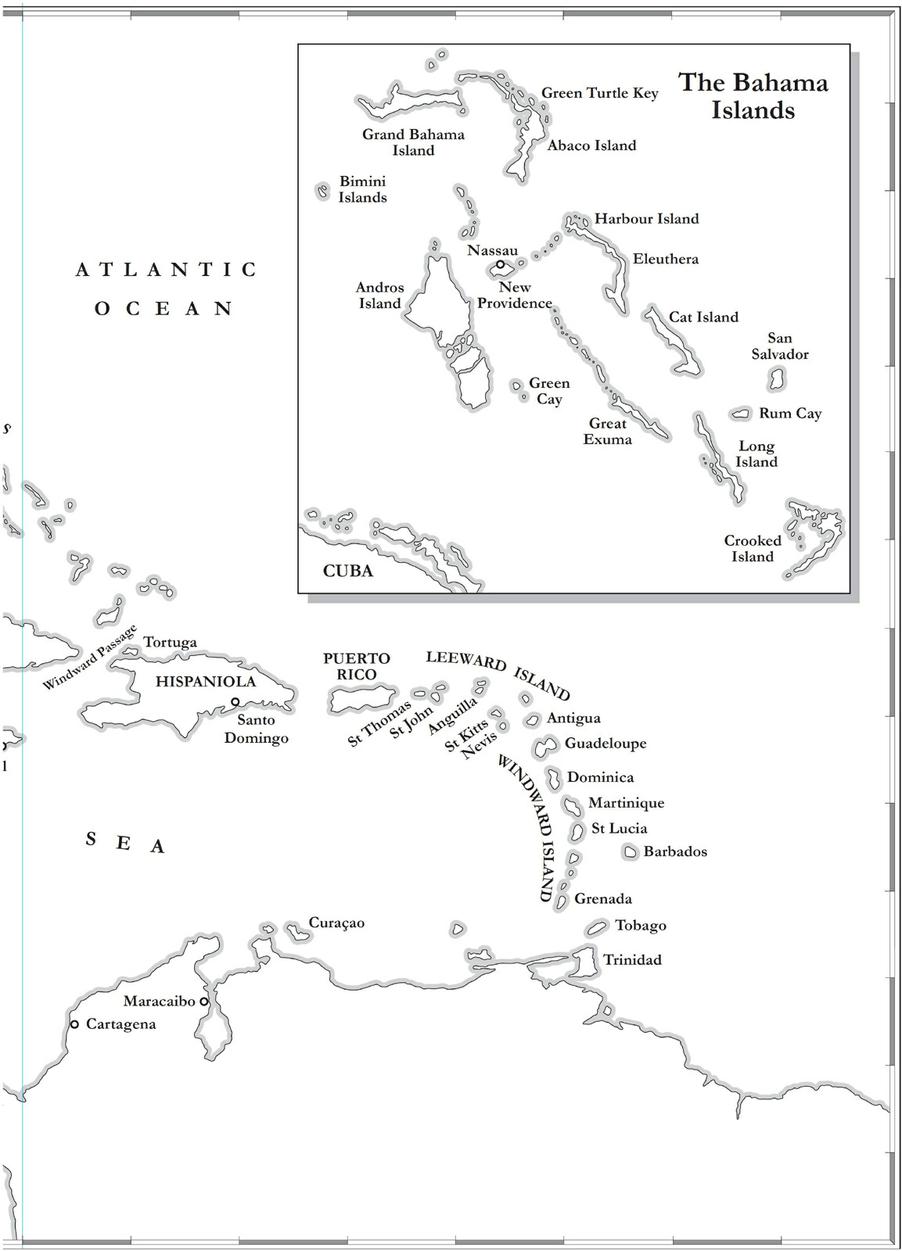

For several years the harbour of Nassau in the Bahamas was the base for a roving band of pirates which included many of the leading figures of the so-called Golden Age of Piracy figures such as Ben Hornigold, Charles Vane, Calico Jack, Sam Bellamy and Edward Teach, otherwise known as Blackbeard. This nucleus of loose and disorderly people produced a generation of pirates whose operations extended from the Caribbean to the east coast of North America as far as Newfoundland, and across the Atlantic to the slave ports of West Africa and beyond to the Indian Ocean. The usual explanation given for this explosion of piracy is the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, which brought an end to eleven years of war and caused Britain, France and other maritime powers to reduce the size of their navies. This threw thousands of redundant sailors on to the streets of coastal towns and cities. Unable to find work elsewhere, some of these seamen turned to piracy. They were joined by the crews of privateer ships who had been legally authorised by letters of marque to attack enemy shipping when their country was at war but, with the declaration of peace, were tempted to exchange their national ensigns for the black flag of piracy.

Redundant sailors and privateers were certainly among the crews of the pirate ships but there were other events which sparked off the alarming surge in piracy following the Treaty of Utrecht. The first was the wrecking of a Spanish treasure fleet on the coast of Florida in 1715. This attracted sailors and adventurers from across the Caribbean to go fishing on the wrecks for Spanish gold and silver. The second was the misguided action of the Spanish in expelling the logwood cutters from the Bay of Campeche in the Gulf of Mexico and the Bay of Honduras. Described by one observer as a rude, drunken crew, some of which have been pirates, and most of them sailors, the logwood men alternated the laborious work of cutting down the valuable logwood trees with extended bouts of heavy drinking. When the Spanish seized the ships involved in the logwood trade, the cutters migrated to Nassau, which was already being used by the treasure hunters as a base for their operations. The sheltered harbour on the north coast of the island of New Providence in the Bahamas became a magnet for a motley group of seafaring men who found piracy to be an easier and more profitable occupation than life on a merchant ship or cutting logs in the steamy jungles of Central America.

Colonial governors sent disturbing reports back to the Council of Trade and Plantations in London. In 1718 the Governor of South Carolina asked for the assistance of a naval frigate to counter the unspeakable calamity this poor province suffers from pyrates It would be the task of Captain Woodes Rogers to rid the islands of the pirates and to put an end to the raids of Spanish privateers.

The Juan Fernndez islands were a refuge for generations of mariners who had rounded Cape Horn and survived the icy storms and mountainous waves of that bleak region. It was here that several buccaneer ships called in for wood and water in the 1680s. During one of these visits a Miskito Indian called Will was inadvertently marooned, his rescue three years later being witnessed and recorded by William Dampier. And it was on the same island that the most famous of castaways, Alexander Selkirk, was abandoned in 1704 after an argument with Captain Stradling, who had parted from an ill-fated privateering expedition led by Dampier. When Captain Woodes Rogers dropped anchor off the island four years later he and his crew were greeted by a man clothed in goat-skins, who looked wilder than the first owners of them. On his return to London after his successful privateering expedition Rogers published a book entitled A Cruising Voyage Round the World which described his raid on the town of Guayaquil and his capture of a Spanish treasure galleon, and included vivid accounts of faraway anchorages and exotic native peoples. But it was his detailed description of how Selkirk survived his lonely ordeal on Juan Fernndez which proved of more interest than anything else which took place during the epic voyage of the two Bristol ships under his command.