Table of Contents

Copyright 2007 by Colin Woodard

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

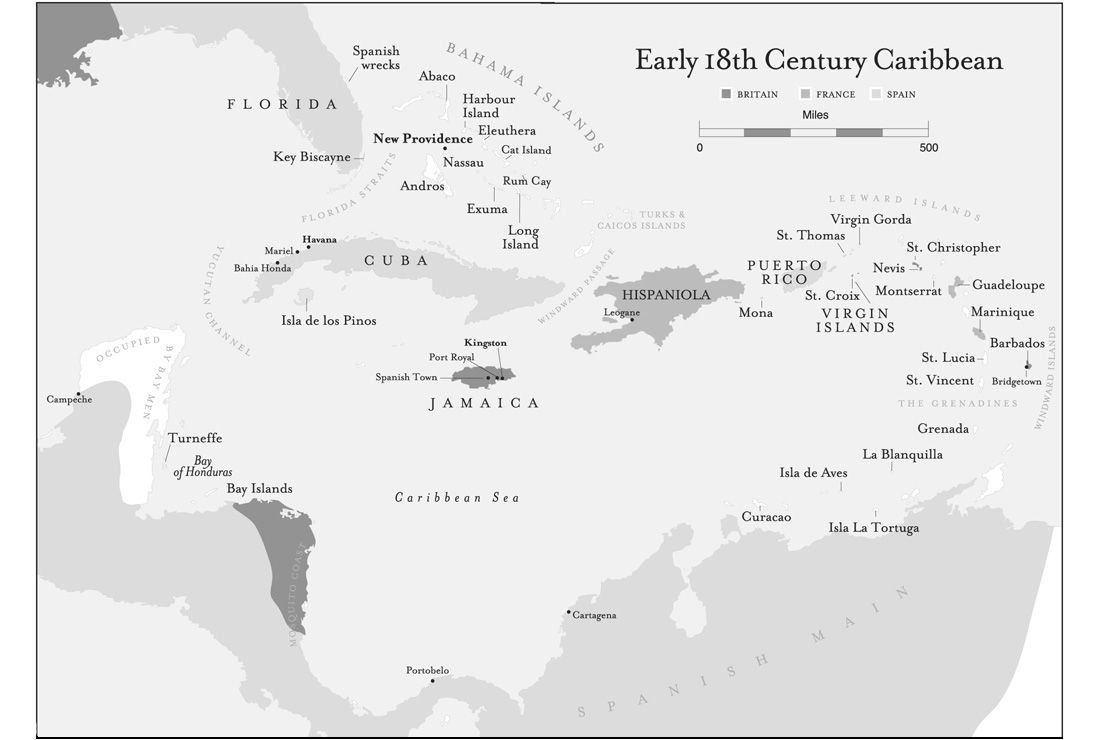

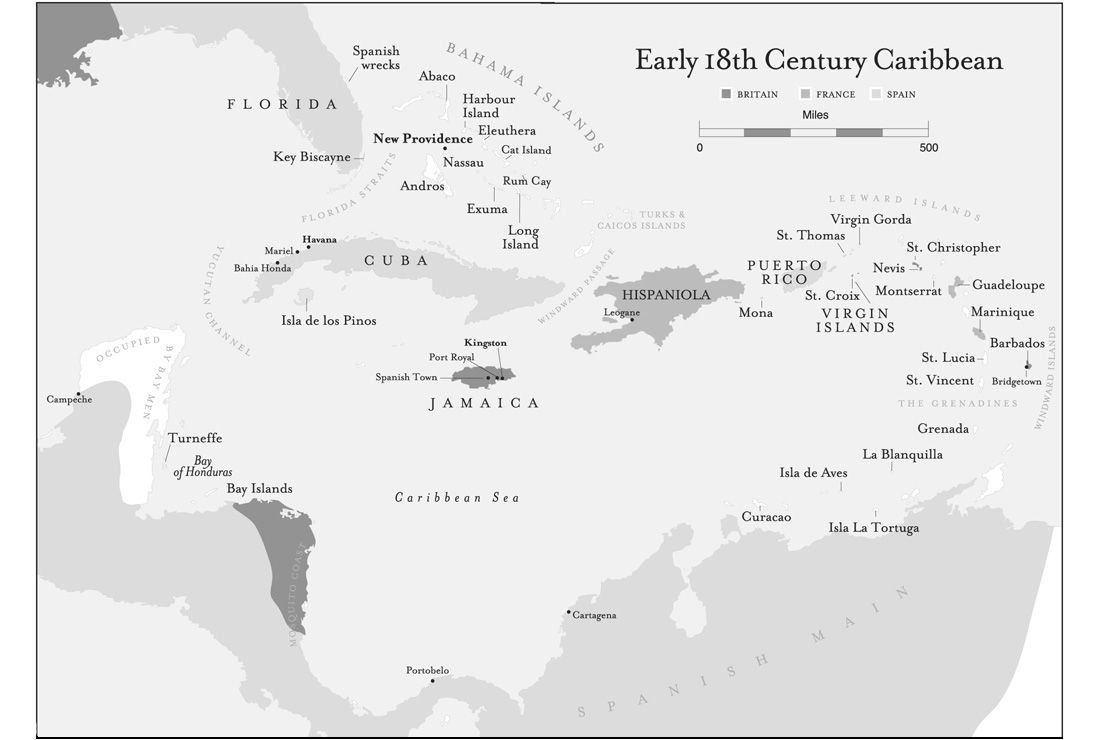

Maps by Jojo Gragasin/LoganFrancis, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Woodard, Colin, 1968

The republic of pirates: being the true and surprising story of the Caribbean

pirates and the man who brought them down/Colin Woodard.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. BuccaneersHistory18th century. 2. PiratesCaribbean Area

History18th century. I. Title.

F2161.W56 2007

910.4'5dc22 2006037389

ISBN 978-0-15-101302-9

e ISBN 978-0-547-41575-8

v3.0414

For Sarah

My wife and true love

Prologue

THE GOLDEN AGE OF PIRACY

T O THEIR ADMIRERS, pirates are romantic villains: fearsome men willing to forge a life beyond the reach of law and government, liberated from their jobs and the constraints of society to pursue wealth, merriment, and adventure. Three centuries have passed since they disappeared from the seas, but the Golden Age pirates remain folk heroes and their fans are legion. They have been the models for some of fictions greatest charactersCaptain Hook and Long John Silver, Captain Blood and Jack Sparrowconjuring images of sword fights, plank walking, treasure maps, and chests of gold and jewels.

Engaging as their legends areparticularly as enhanced by Robert Louis Stevenson and Walt Disneythe true story of the pirates of the Caribbean is even more captivating: a long-lost tale of tyranny and resistance, a maritime revolt that shook the very foundations of the newly formed British Empire, bringing transatlantic commerce to a standstill and fueling the democratic sentiments that would later drive the American revolution. At its center was a pirate republic, a zone of freedom in the midst of an authoritarian age.

The Golden Age of Piracy lasted only ten years, from 1715 to 1725, and was conducted by a clique of twenty to thirty pirate commodores and a few thousand crewmen. Virtually all of the commodores knew one another, having served side by side aboard merchant or pirate vessels or crossed paths in their shared base, the failed British colony of the Bahamas. While most pirates were English or Irish, there were large numbers of Scots, French, and Africans as well as a smattering of other nationalities: Dutch, Danes, Swedes, and Native Americans. Despite differences in nation, race, religion, and even language, they forged a common culture. When meeting at sea, pirate vessels frequently joined forces and came to one anothers aid, even when one crew was largely French and the other dominated by their traditional enemies, the English. They ran their ships democratically, electing and deposing their captains by popular vote, sharing plunder equally, and making important decisions in an open councilall in sharp contrast to the dictatorial regimes in place aboard other ships. At a time when ordinary sailors received no social protections of any kind, the Bahamian pirates provided disability benefits for their crews.

Even the infamous Captain William Kidd was a well-born privateer who became a pirate accidentally, by running afoul of the directors of the East India Company, Englands largest corporation.

The Golden Age Pirates were distinct from both the buccaneers of Morgans generation and the pirates who preceded them. In contrast with the buccaneers, they were notorious outlaws, regarded as thieves and criminals by every nation, including their own. Unlike their pirate predecessors, they were engaged in more than simple crime and undertook nothing less than a social and political revolt. They were sailors, indentured servants, and runaway slaves rebelling against their oppressors: captains, ship owners, and the autocrats of the great slave plantations of America and the West Indies.

Dissatisfaction was so great aboard merchant vessels that typically when the pirates captured one, a portion of its crew enthusiastically joined their ranks. Even the Royal Navy was vulnerable; when HMS Phoenix confronted the pirates at their Bahamian lair in 1718, a number of the frigates sailors defected, sneaking off in the night to serve under the black flag. Indeed, the pirates expansion was fueled in large part by the defections of sailors, in direct proportion to the brutal treatment in both the navy and merchant marine.

Not all pirates were disgruntled sailors. Runaway slaves migrated to the pirate republic in significant numbers, as word spread of the pirates attacking slave ships and initiating many aboard to participate as equal members of their crews. At the height of the Golden Age, it was not unusual for escaped slaves to account for a quarter or more of a pirate vessels crew, and several mulattos rose to become full-fledged pirate captains. This zone of freedom threatened the slave plantation colonies surrounding the Bahamas. In 1718, the acting governor of Bermuda reported that the negro men [have] grown so impudent and insulting of late that we have reason to suspect their rising [against us and]... fear their joining with the pirates.

Some pirates had political motivations as well. The Golden Age erupted shortly after the death of Queen Anne, whose half-brother and would-be successor, James Stuart, was denied the throne because he was Catholic. The new king of England and Scotland, Protestant George I, was a distant cousin of the deceased queen, a German prince who didnt care much for England and couldnt speak its language. Many Britons, including a number of future pirates, found this unacceptable and remained loyal to James and the House of Stuart. Several of the early Golden Age pirates were set up by the governor of Jamaica, Archibald Hamilton, a Stuart sympathizer who apparently intended to use them as a rebel navy to support a subsequent uprising against King George. As Kenneth J. Kinkor of the Expedition Whydah Museum in Provincetown, Massachusetts, puts it, these were more than just a few thugs knocking over liquor stores.

The pirate gangs of the Bahamas were enormously successful. At their zenith they succeeded in severing Britain, France, and Spain from their New World empires, cutting off trade routes, stifling the supply of slaves to the sugar plantations of America and the West Indies, and disrupting the flow of information between the continents. The Royal Navy went from being unable to catch the pirates to being afraid to encounter them at all. Although the twenty-two-gun frigate HMS Seaford was assigned to protect the Leeward Islands, her captain reported he was in danger of being overpowered if he were to cruise against the pirates. By 1717, the pirates had become so powerful they were able to threaten not only ships, but entire colonies. They occupied British outposts in the Leeward Islands, threatened to invade Bermuda, and repeatedly blockaded South Carolina. In the process, some accumulated staggering fortunes, with which they bought the loyalty of merchants, plantation owners, even the colonial governors themselves.

Next page