ALSO BY MARCUS REDIKER

Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: Merchant Seamen, Pirates, and the Anglo-American Maritime World, 17001750

The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (with Peter Linebaugh)

To learn more about Marcus Rediker and his work, please visit http://www.MarcusRediker.com.

Villains of All Nations

ATLANTIC PIRATES IN THE GOLDEN AGE

MARCUS REDIKER

Beacon Press, Boston

In memory of

Michael Jimnez (19482001)

and

Steve Sapolsky (19482001)

Contents

1. A Tale of Two Terrors

IN THE EARLY AFTERNOON of July 12, 1726, William Fly ascended Bostons gallows to be hanged for piracy. His body was nimble in manner, like a sailor going aloft; his rope-roughened hands carried a nosegay of owers; his weather-beaten face had a Smiling Aspect. He showed no guilt, no shame, and no contrition. Indeed, as attending minister Cotton Mather noted, he lookd about him unconcerned. But once he stood on the gallows, he became concerned, although not in the way anyone might have expected. His demeanor quickened, and he immediately took charge of the stage of death. He threw the hanging rope over the beam, made it fast, and carefully inspected the noose that would go around his neck. He soon turned to the hangman in disappointment and reproached him for not understanding his Trade. But Fly, a sailor who knew the art of tying knots, took mercy on the novice. He offered to teach him how to tie a proper noose. Then Fly, with his own Hands[,] rectied Matters, to render all things more Convenient and Effectual, retying the knot himself as the multitude who had gathered around the gallows looked on in astonishment. He informed the hangman and the crowd that he was not afraid to die, that he had wrongd no Man. Mather explained that he was determined to die a brave fellow.

When the time came for last words on that awful occasion, Mather wanted Fly and his fellow pirates to act as preachersthat is, he wanted them to provide examples and warnings to those who were assembled to watch the execution.

High drama had surrounded Fly and his crew from the moment they were brought into port as captives on June 28, 1726. Fly was a twenty-seven-year-old boatswain, a poor man of very obscure Parents, who had signed on in Jamaica in April 1726 to sail with Captain John Green to West Africa on the Elizabeth , a snow (two-masted vessel) based in Bristol. Green and Fly soon clashed, and the boatswain began to organize a mutiny against Greens command. Fly and another sailor, Alexander Mitchell, roused Green from his sleep late one night, forced him on deck, beat him, and attempted to throw him over the side of the ship. When Green caught hold of the mainsheet, one of the sailors picked up the coopers broad ax and chopped off the captains hand at the wrist. Poor Green was swallowed up by the Sea. The mutineers then turned the ax on Thomas Jenkins, the rst mate, and threw him, still alive, overboard after the captain. They debated whether their messmate, the ships doctor, should follow them into the blue, but a majority of the crew decided he might prove useful and conned him in irons instead.

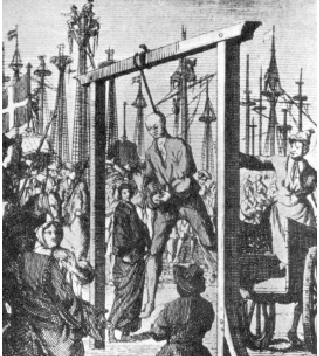

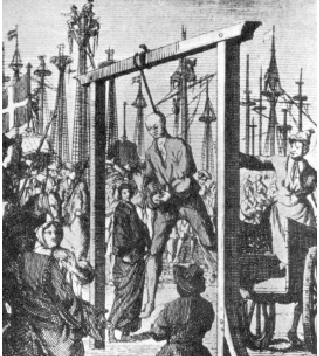

Figure 1. The hanging of pirate captain Stede Bonnet, Charleston, November 1718; Captain Charles Johnson, A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates (London, 1724).

Having taken possession of the ship, the mutineers prepared a bowl of punch and ceremoniously installed a new shipboard order of things. These sailors, who routinely sewed canvas sails and were therefore expert with needle and thread, stitched a skull and crossbones onto a black ag, creating the Jolly Roger, the pirates traditional symbol and instrument of terror. They renamed their vessel the Fames Revenge and sailed away in search of prizes. They captured ve vessels. After taking the John and Hannah off the coast of North Carolina, Fly punished its captain, John Fulker, by tying him to the geers and lashing him before sinking his ship. Flys piratical adventures came to an end when a group of men he had forced aboard the pirate ship from prize vessels rose up and captured him. Fly and his crew were brought into Boston Harbor to stand trial for murder and piracy.

Awaiting them in Boston was the Reverend Doctor Cotton Mather, the pompous, vain, and overbearing sixty-three-year-old minister of Old North Church who was probably the most famous cleric, maybe even the most famous person, in the American colonies at the time.

The hanging of the poor man William Fly was a moment of terror. Indeed, it might be said that the occasion represented a clash of two different kinds of terror. One was practiced by the likes of Cotton Mathernamely, ministers, royal officials, wealthy men; in short, rulersas they sought to eliminate piracy as a crime against mercantile property. They consciously used terror to accomplish their aims: to protect property, to punish those who resisted its law, to take vengeance against those they considered their enemies, and to instill fear in sailors who might wish to become pirates. This they did in the name of the social order, as suggested by Colman, whose execution sermon (which Fly refused to attend) was a meditation on terror, on God as the king of terrors and hence the source of all social discipline. In truth, the keepers of the state in this era were themselves terrorists of a sort, decades before the word terrorist would acquire its modern meaning (as it would do in the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution). And yet we do not think of them in this way. They have become, over the years, cultural heroes, even founding fathers of sorts. Theirs was a terror of the strong against the weak.

The other kind of terror was practiced by common seamen like William Fly who sailed beneath the Jolly Roger, the ag designed to terrify the captains of merchant ships and persuade them to surrender their cargo. Pirates consciously used terror to accomplish their aimsto obtain money, to punish those who resisted them, to take vengeance against those they considered their enemies, and to instill fear in sailors, captains, merchants, and officials who might wish to attack or resist pirates. This they did in the name of a different social order, as we will see in the chapters that follow. In truth, pirates were terrorists of a sort. And yet we do not think of them in this way. They have become, over the years, cultural heroes, perhaps antiheroes, and at the very least romantic and powerful gures in an American and increasingly global popular culture. Theirs was a terror of the weak against the strong. It formed one essential part of a dialectic of terror, which was summarized in the decision of the authorities to raise the Jolly Roger above the gallows when hanging pirates: one terror trumped the other.

The dramas involving piratesWilliam Fly and the dozens of others we will meet in the pages that followconcerned the fundamental issues of the age. As we will see, poor seamen who turned pirate dramatized concerns of class. Formerly enslaved Africans or African Americans who turned pirate posed questions of race. Women who turned pirate called attention to the conventions of gender. And all people who turned pirate and sailed under their own dark ag, the Jolly Roger, enacted a highly political play about the nation. These events had their own theater, in both senses of the worda specic geography and a particular dramatic form. They took place around the Atlantic, on the hastily constructed scaffolds of port-city gallows as in Boston, and on the heaving decks of deep-sea ships, as on the Fames Revenge . The stages were transient, in motion, and simultaneously local and global, as were the subjects who acted on them.