Pirates and Privateers in the 18th Century

Dedicated to Luca and Maya Human, the twin terrors of the Southern Ocean!

Pirates and Privateers in the 18th Century

The Final Flourish

Mike Rendell

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

Pen & Sword History

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire - Philadelphia

Copyright Mike Rendell, 2018

ISBN 978 1 52673 165 4

eISBN 978 1 52673 165 4

MOBI ISBN 978 1 52673 165 4

The right of Mike Rendell to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Books Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing, Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS,

England E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Preface

Mention the word pirate to most people and they will summon up an image of a swashbuckling buccaneer, shouting in a mock-Cornish accent and using phrases such as Heave-ho me hearties and Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum! They will think of the heroic figures from films such as The Pirates of the Caribbean . They may bring to mind booze cruises in the Caribbean on board the Black Pearl as she sailed into the sunset. They may think of buried treasure and bearded men armed with cutlasses. But what they probably will not think of is theft, rape, murder, arson and torture. Yet, sweeping aside the nostalgia and putting down the rose-tinted spectacles, that was, more often than not, the reality of piracy in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The period is said to be the Golden Age of Piracy as if it was something vaguely noble and aspirational. This golden age, lasting from perhaps 1650 to 1730, is divided into three parts up to 1680; from 1680 to 1710; and from 1710 to 1730. Each period had its own characteristics and the object of this book is to look behind the myths, to consider the importance of piracy and privateering to the British economy, and to see how and why piracy came to be seen as an almost virtuous, anodyne, past-time. It looks, in particular, at the third and final phase of the golden age, while at the same time showing how it differed from its earlier manifestations.

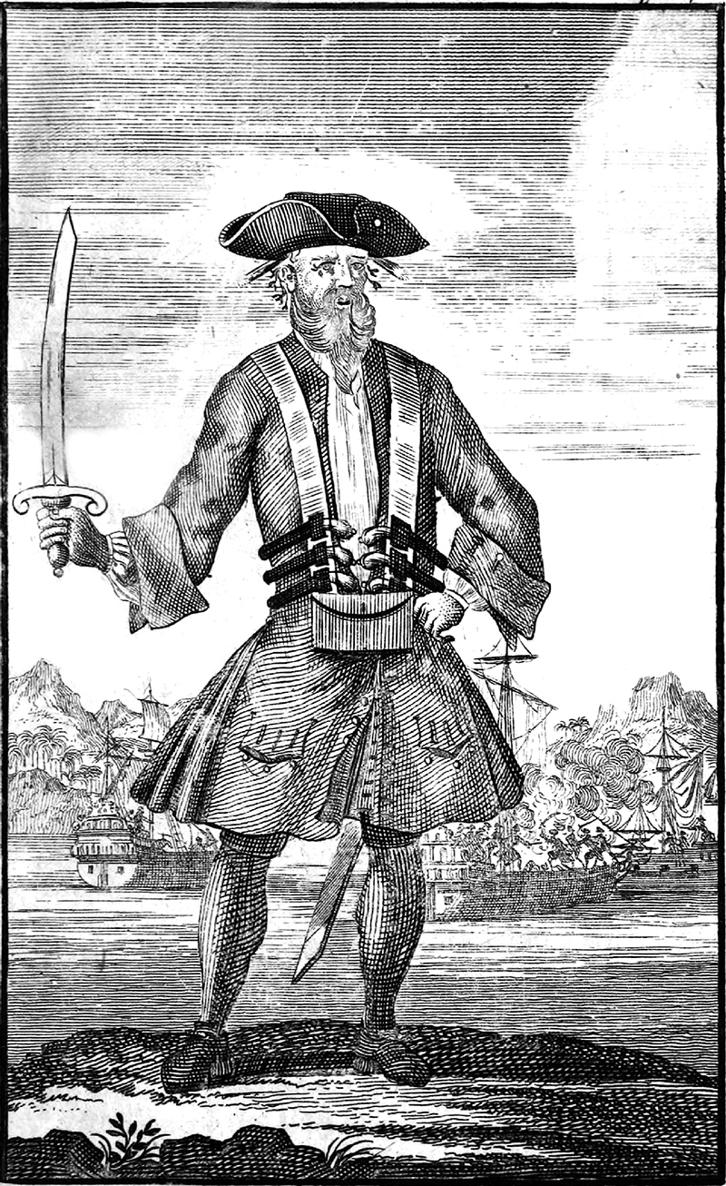

Some of the pirates are household names, whereas some are almost lost to history. And because pirates did not often sit down in the genteel surroundings of the artists studio, they rarely had their picture painted at least not in their lifetime. So, in many cases we have little idea of what they actually looked like. There are woodcuts particularly from a book published in 1724 but these may or may not bear any resemblance to the men portrayed.

This book is intended to consider pirates and privateers in the context of the era in which they lived, rather than viewing them from a twenty-first-century perspective. They lived their lives in their time, not ours, and we should not rush to judge them by our own standards.

The pirate Edward Teach, a.k.a. Blackbeard.

Part One

B ACKGROUND

A seventeenth century Spanish galleon.

Chapter 1

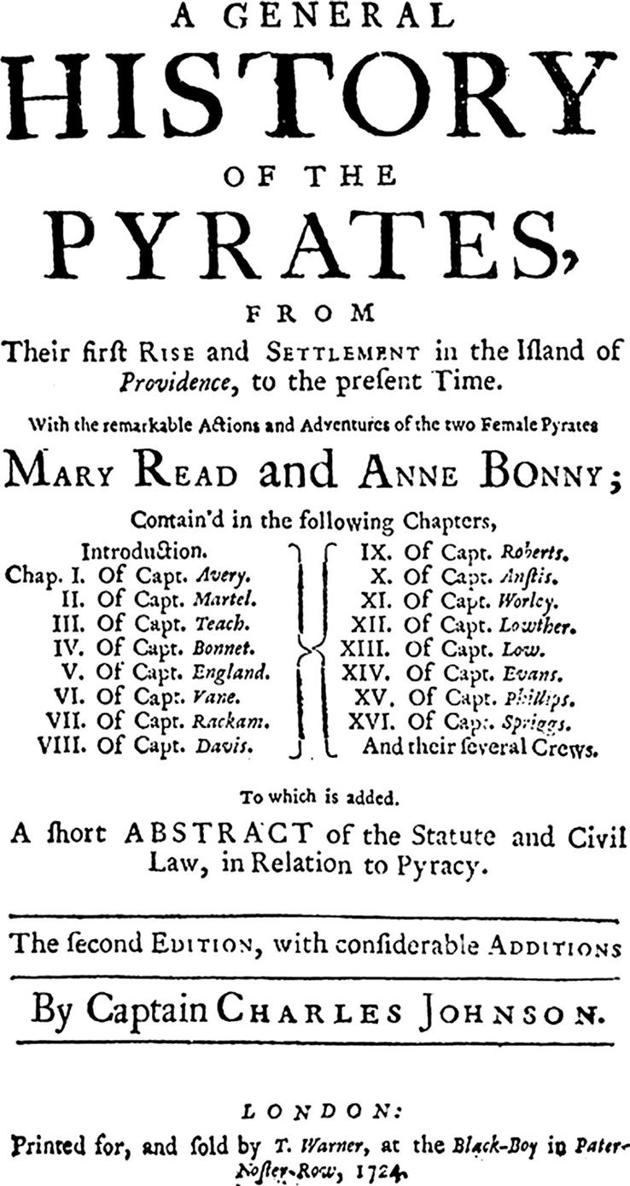

A General History of the Pyrates

This present book is about pirates and privateers, particularly during the final phase of their golden age. It is, however, important to distinguish between the two groups. Piracy was illegal. It was regarded as a threat to international trade; its practitioners were despised and reviled. Pirates were seen as the scum of the earth, a menace to society. Privateers on the other hand were patriotic sailors serving the interests of their country; hard-working and pursuing a noble cause. In practice, both groups did precisely the same thing they went to sea in order to capture other vessels, to loot their cargoes and to grow rich on the proceeds of plunder. The only difference between the two groups was that privateering was legal encouraged by a government which found it convenient to leave private individuals to implement foreign policy without involving the state in expense or responsibility. The distinction between pirate and privateer was that the latter held a Letter of Marque, but even this distinction was blurred, because many privateers exceeded their authority and stepped over into piracy. Other pirates became privateers at least in their own minds because they managed to purchase a Letter of Marque corruptly, or simply joined up with other privateers to form a mixed squadron of vessels lying in wait for their prey.

Admiral Horatio Nelson was one person who saw little distinction between the two classes of mariner, writing that the conduct of all privateers is, as far as I have seen, so near piracy that I only wonder any civilized nation can allow them.

Where the distinction between piracy and privateering is unclear, it is easier to use the term buccaneer because it avoids making a distinction. The word comes from the Carib word buccan meaning a wooden frame on which strips of meat would be air-dried. The meat was often eaten by sailors throughout the Caribbean hence buccaneers. Strictly speaking it does not therefore apply to the Brethren (as pirates sometimes called themselves) in other parts of the world.

It is difficult to escape the conclusion that if the person committing the piratical act was British, it was viewed in Britain in a wholly different light from an act by, say, a Frenchman or a Spaniard. Even more xenophobic, if the victims were Indian, or from one of the countries bordering the Arabian Gulf, then this was seen almost as a just dessert they were too rich for their own good, and relieving them of their jewels and vast fortunes was in some way fair.