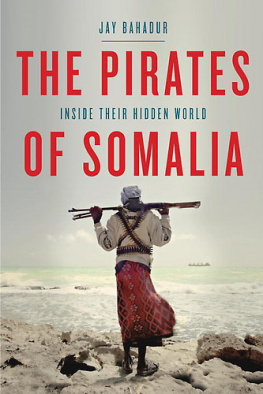

Copyright 2011 by Jay Bahadur

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Published simultaneously in Canada by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd., Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

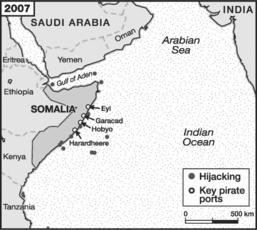

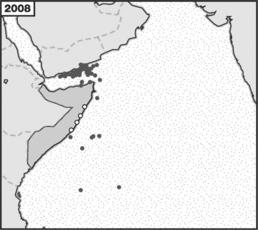

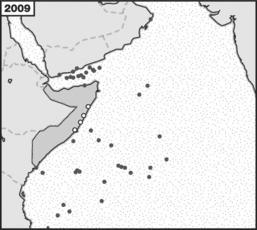

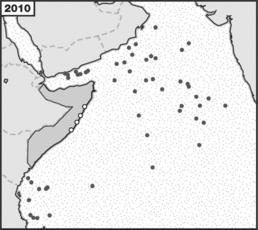

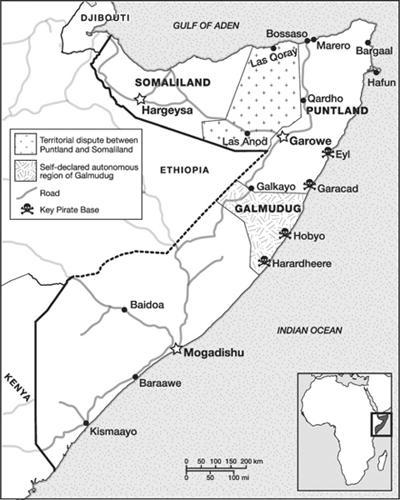

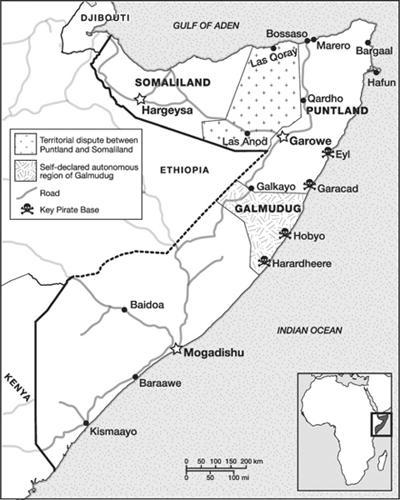

Maps on by Susan MacGregor/Digital Zone.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bahadur, Jay.

The pirates of Somalia : inside their hidden world / Jay Bahadur.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-90698-4

1. PiratesSomalia21st century. 2. PiracySomalia21st century.

3. Hijacking of shipsSomalia21st century. 4. Puntland (Somalia)Economic conditions. 5. SomaliaPolitics and government1991

6. Bahadur, JayTravelSomaliaPuntland. I. Title.

DT403.2.B34 2011 364.164096773dc22 2011011731

www.pantheonbooks.com

Jacket illustration by Mohamed Dahir/AFP/Getty Images

Jacket design by Peter Mendelsund

v3.1

To Ali, without whose infectious love for Africa

this book would not exist

Contents

Somalia

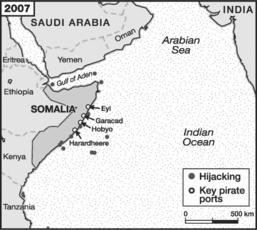

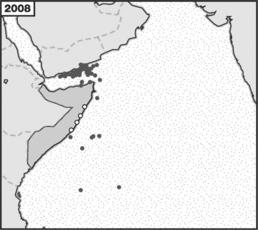

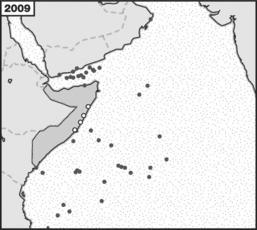

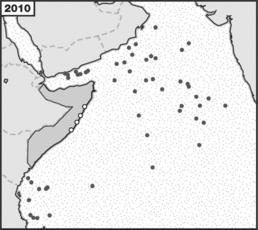

Expansion of Pirate Operations

Prologue

Where the White Man Runs Away

I T WAS MY FIRST TRIP TO A FRICA .

I arrived in Somalia in the frayed seat of a 1970s Soviet Antonov propeller plane, heading into the internationally unrecognized region of Puntland on a solo quest to meet some present-day pirates. The 737s of Dubai, with their meal services and functioning seatbelts, were a distant memory; the plane I was in was not even allowed to land in Dubai, and the same probably went for the unkempt, ill-tempered Ukrainian pilot.

To the ancient Egyptians, Punt had been a land of munificent treasures and bountiful wealth; in present times, it was a land of people who robbed wealth from the rest of the world. Modern Puntland, a self-governing region in northeastern Somalia, may or may not be the successor to the Punt of ancient times, but I was soon to discover that it contained none of the gold and ebony that dazzled the Egyptianssave perhaps for the colours of the sand and the skin of the nomadic goat and camel herders who had inhabited it for centuries.

The cabin absorbed the heat of the midday African sun like a Dutch oven, thickening the air until it was unbearable to breathe. Sweat poured freely off my skin and soaked into the torn cloth of my seat cover. Male passengers fanned themselves with the Russian-language aircraft safety cards; the women fanned their children. The high whine of the Antonovs propellers changed pitch as it accelerated along the Djibouti runway, building towards a droning crescendo that I had not heard outside of decades-old movies.

The stories I had heard of these planes did nothing to put me at ease: a vodka-soaked technician banging on exposed engine parts with a wrench; a few months prior, a plant-nosed landing at Bossaso airstrip after a front landing strut had refused to extend. Later, in Bossaso, I saw the grounded craft, abandoned where it had crashed, a few lackadaisical guards posted nearby to prevent people from stripping the valuable metal.

This flight was like a forgotten relic of the Cold War, a physical testament to long-defunct Somali-Soviet geopolitical ties that had disintegrated with the countries themselves; its Ukrainian crew, indentured servants condemned forever to ferry passengers along this neglected route.

Over the comm system, the Somali steward offered a prayer in triplicate: Allahu akbar, Allahu akbar, Allahu akbar , as the plane gained speed. The whine heightened to a mosquito-like buzz and we left the ground behind, setting an eastward course for Somalia, roughly shadowing the Gulf of Aden coastline.

* * *

As I approached my thirty-fifth weary hour of travel, my desire to socialize with fellow passengers had diminished, but on purely self-serving grounds I forced myself to chat eagerly with anyone throwing a curious glance in my direction. I had never met my Somali host, Mohamad Farole, and any friend I made on the plane was a potential roof over my head if my ride didnt show. Remaining alone at the landing strip was not an option; news travels around Somalia as fast as the ubiquitous cellphone towers are able to transmit it, and a lone white man bumming around the airstrip would be public knowledge sooner than I cared to contemplate.

When he learned that I was travelling to Garowe, Puntlands capital city, the bearded man sitting next to me launched into the unfortunate tale of the last foreigner he knew to make a similar voyage: a few months previous, a Korean man claiming to be a Muslim had turned up in the capital, alone and unannounced. Not speaking a word of Somali, he nonetheless succeeded in finding a residence and beginning a life in his unusual choice of adoptive homeland.

He lasted almost two weeks. On his twelfth day in Puntland, a group of rifle-toting gunmen accosted the man in broad daylight as he strolled unarmed through the streets. Rather than let himself be taken hostage, the Korean made a fight of it, managing to struggle free and run. He made it several metres before one of his bemused would-be captors casually shot him in the leg. The shot set off a hue and cry, and in the ensuing clamour the gunmen dispersed and someone helped the man reach a medical clinic. I later learned from another source that he was a fugitive, on the run from the Korean authorities. His thought process, I could only assume, was that Somalia was the last place on earth that his government would look for him. He was probably right.

* * *

Just a few months earlier, I had been a recent university graduate, killing the days writing tedious reports for a market research firm in Chicago, and trying to break into journalism with the occasional cold pitch to an unresponsive editor. I had no interest in journalism school, which I thought of as a waste of two of the best years of my lifeyears that I should spend in the fray, learning how to do my would-be job in places where no one else would go.

Somalia was a good candidate, jockeying with Iraq and Afghanistan for the title of the most dangerous country in the world. The country had commanded a soft spot in my heart since my PoliSci days, when I had wistfully dreamt of bringing the astounding democratic success of the tiny self-declared Republic of Somaliland (Puntlands western neighbour) to the worlds attention.

The headline-grabbing hijacking of the tank transport MV Faina in September 2008 presented me with a more realistic opportunity. I sent out some feelers to a few Somali news services, and within ten minutes had received an enthusiastic response from Radio Garowe, the lone news outlet in Puntlands capital city. After a few long emails and a few short phone calls with Radio Garowes founder, Mohamad Farole, I decided to buy a ticket to Somalia.

It took multiple tickets, as it turned out. Getting to Somalia was an aerophobes nightmarea forty-five-hour voyage that took me through Frankfurt, Dubai, Djibouti, Bossaso, and finally Galkayo. In Dubai, I joined the crowd of diaspora Somalis, most making short visits to see their families, pushing cart upon cart overflowing with goods from the outside world. Curious eyes began to glance my way, scanning, no doubt, for signs of mental instability. I was in no position to help them make the diagnosis; by the first leg of my trip, I had already lost the ability to judge objectively whether what I was doing was sane or not. News reports of the numerous journalists kidnapped in Puntland fixated my imagination. I channelled the hours of nervous energy into studying the lone Somali language book I had been able to dig up at the public library; I scribbled answers to exercises into my notebook with an odd sense of urgency, as if cramming for an exam that would take place as soon as I set foot in Somalia.

Next page

Expansion of Pirate Operations

Expansion of Pirate Operations