CAMPAIGN 198

THE SAMURAI INVASION OF KOREA 159298

|

| STEPHEN TURNBULL | ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS |

| Series editors Marcus Cowper and Nikolai Bogdanovic |

CONTENTS

Kido Norishige performed an unusual feat during the capture of Seoul in 1592. The city gates were securely locked, so Norishige fastened several gun barrels together to make a stout lever and prised open the grille that was covering a water gate.

THE STRATEGIC SITUATION

Even though the invasion of Korea was an act of unprovoked aggression by Japan against its immediate neighbour, the campaign has to be seen in the context of the overall strategic situation that existed in East Asia during the last quarter of the 16th century. It was a position dominated by China and its great empire of the Ming dynasty, whose pre-eminence was threatened in 1592 by a small island neighbour that had been obsessed with its own internal wars for over a hundred years. On previous occasions the lawless state of Japan had affected China in the form of pirate raids, but it was the very fact of Japanese disunity that had led it to pose no major threat to the stability of the Ming. This situation was to change radically in 1591, when Japan became reunited under one sword.

The reunification of Japan was achieved by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (153298). After a long military campaign that had reached from one end of Japan to another, Hideyoshi had brought to a close the century of sporadic civil war that historians have dubbed the Sengoku Jidai (The Age of Warring States), a term used by analogy with the period of that name in ancient Chinese history. It may therefore appear somewhat surprising that within one year of having achieved peace at home, the undisputed ruler of Japan should immediately seek war overseas; particularly when one considers that the Korean invasion remains the only major act of aggression by Japan against a neighbouring country within one thousand years of its history.

Admiral Yi Sunsin, the greatest hero of the defeat of the samurai invasion of Korea, is shown here discussing his plans for the battle of Okpo, Koreas first victory over the invaders as shown on this modern painting in the Okpo Memorial Museum on Kje Island, South Korea.

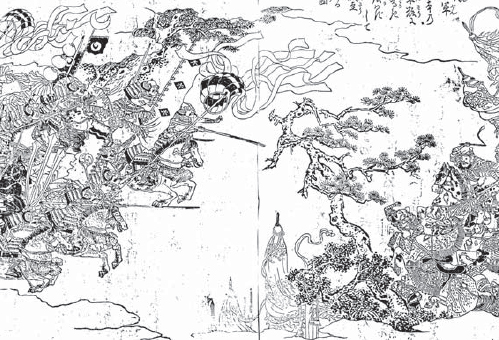

Konishi Yukinaga, who played a prominent role throughout the campaign, leads a Japanese attack on Ming soldiers. From Ehon Taikki, an illustrated life of Hideyoshi.

Yet the Korean expedition did not come from nowhere, and the most important trigger to action was Hideyoshis own grandiose dream of overseas military conquest. There is considerable evidence that he had been planning such a move for several years as the logical extension of his unstoppable triumphs at home. When Hideyoshi received Father Gaspar Coelho, the vice-principal of the Jesuit mission in Japan, in 1585, he disclosed to him his plans for overseas expansion and asked for two Portuguese ships to be made available, a request that was politely refused. Two years later, while setting off on the Kysh campaign, Hideyoshi told his companions of his intention to slash his way into Korea and China. In fact his personal ambitions went further than Korea and China, and included the conquest of Taiwan, the Philippines and even India.

Hideyoshis expectation that an international act of aggression would be an unqualified success was fully in keeping with his experience of domestic Japanese warfare over the past two decades. As his power grew he would request rival daimy (warlords) to pay homage to him and accept vassal status. If they refused they were attacked by Hideyoshis increasingly professional army. Hideyoshi was a generous victor, so that mass acts of suicide or battles to the death were rare events during his campaigns, and upon their submission the defeated daimy were usually acknowledged in their existing possessions on agreeing to accept the status that they had once so unwisely declined. To treat Korea and even China in this way could well have seemed a natural progression for a successful general who had demonstrated, among his other accomplishments, the ability to move large numbers of soldiers over large distances, including across the sea. The Japanese army was well equipped and battle hardened, so to take on Korea and even Ming China with its vast resources theoretically available to oppose him, was not such a big gamble.

The horrors inflicted by the Japanese during the invasion of Korea brought back memories of the dark days of the wak raids, as shown on this modern painting in the Okpo Memorial Museum on Kje Island, South Korea.

From a wider political perspective Hideyoshis desire to make Korea and China into his vassal states may have been presumptive, but it was fully in the context of the way that international relations had long been handled from the Chinese side. To make China a vassal state of a neighbouring country would simply reverse the position that had existed for centuries, whereby China regarded itself as the centre of the world with its neighbours as its children. To the Ming emperors this dependent relationship was the basis of international trade and harmony. China was a universal and benevolent empire whose sovereignty had to be acknowledged by its less fortunate barbarian neighbours before the benefits of commerce could be bestowed. These supplicant barbarians must first pay homage to the Chinese emperor, who would then graciously bestow upon them titles and privileges such as being acknowledged by China as rulers of their own countries. In deep gratitude they would then bring tribute to his feet, and gifts would be showered upon them in return.

This exchange of tribute for gifts contained the essence of trade, and fruitful commercial transactions flowed from it, so most trading missions to China played along with the bizarre pantomime. Japan had always tended to be an exception to the rule, although, according to the first Ming emperor, the Japanese had entered into such a tributary relationship as early as the Han dynasty (202 BC to AD 220). In more recent memory the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (13581408) had indeed formally accepted vassal status and tribute trade had flourished, but with the collapse of the shoguns authority during the Age of Warring States any kowtowing by Japan to China in this way had long ceased. Sino-Japanese relations were now characterized by an aggressive attitude towards international trading rights that was manifested through the depredations of the wak (Japanese pirates). In spite of their name many wak, and some of their most notorious leaders, were actually Chinese, who organized devastating raids against China and Korea from the 1540s onwards. In response the Ming had severed both trade and tribute with Japan, but as these independent-minded buccaneers lived outside the frame of Japanese legality anyway it was a slur that worried none of them. Some of their raids were so huge that they amounted to mini-invasions of China. Thousands of

Next page