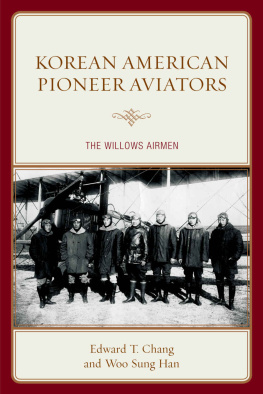

Korean American Pioneer Aviators

Korean American Pioneer Aviators

The Willows Airmen

Edward T. Chang and Woo Sung Han

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Lexington Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2015 by Lexington Books

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chang, Edward T.

Korean American pioneer aviators : the Willows airmen / Edward T. Chang and Woo Sung Han.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4985-0264-1 (cloth : alkaline paper) -- ISBN 978-1-4985-0265-8 (electronic)

1. Air pilots--California--Willows--History--20th century. 2. Air pilots--California--Willows--Biography. 3. Korean Americans--California--Willows--Biography. 4. Koreans--California--Willows--Biography. 5. Willows Korean Aviation School--History. 6. Air pilots--Training of--California--Willows--History--20th century. 7. Willows (Calif.)--Ethnic relations--History--20th century. 8. United States--Relations--Korea. 9. Korea--Relations--United States. 10. Korea--History--Autonomy and independence movements. I. Han, Woo Sung. II. Title.

TL522.C2C47 2015

629.13092'3957073--dc23

2015004318

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Preface

Koreans in America: from Farmers to Independence Activists

Korean diaspora in America is closely linked and connected with Korean migration to China, Japan, and the former Soviet Union (Many Koreans often boarded ships to America once they arrived in China), as well as socio-political conditions in Korea. It is a widely held belief that Korean emigration to the United States began when more than 7,200 Koreans arrived in Hawaii as sugar plantation laborers between 1903 and 1905. With the arrival of 102 Korean laborers in Honolulu, Hawaii, on January 13, 1903, official Korean immigration had begun. In fact, Congress officially designated January 13 as Korean American Day, and in 2003, the Korean American community commemorated the centennial anniversary of Korean immigration to the United States.

Between 1910 and 1940, approximately 1,000 Korean students, picture brides, wives, and children arrived and sought admission to the United States through the port of San Francisco. Since Korea was a colony of Japan, Koreans were legally Japanese subjects. However, Korean immigrants in the United States refused to be identified as Japanese and insisted on their Korean national identity.

Meanwhile, the Hawaiian Sugar Plantation Association adopted a conscious strategy to diversify its labor force in order to prevent workers from organizing a labor union. The divide and control strategy resulted in bringing 400,000 workers from 33 different countries between 1860 and 1940.

The Hawaiian Sugar Plantation Association sent David Deshler to Korea to recruit laborers. The association promised Deshler pay on a per capita basis as well as the profit he could make by transporting Korean laborers from Incheon, Korea, to Kobe, Japan, on his steamship. Initially, Deshler faced several major obstacles, and it was not easy for him to recruit Korean workers. First, Korea did not have an organizational structure to oversee the emigration process. Prior to 1905, Korea was still ruled by a monarchy. Consequently, the King of Korea had to issue permission for Koreans to emigrate, and the Korean government had to establish the Su Min Won to handle the emigration process and issue passports. Second, Koreans proved reluctant to leave their ancestors graves, as they felt obligated to honor their customs and beliefs through ancestral worship. The third obstacle Deshler faced was how to finance the transportation fee of Korean laborers, as costs amounted to roughly 100 dollars per person.

The Hawaiian Sugar Plantation Association instructed David Deshler to set up a bank in Incheon, KoreaDeshlers Bank. The association provided Deshler with funds. The Deshler Bank advanced transportation fees to Koreans who wanted to go to Hawaii. The Korean workers could then pay back the fee from their paychecks over a three-year period.

Deshler successfully recruited thousands of Koreans as Hawaiian sugar plantation workers. The reason for his success was multifaceted, including a religious factor. According to researcher Wayne Patterson, American recruiters seeking Korean labor for Hawaii met with success largely because of their connections to Protestant missionaries who urged their new parishioners to leave their homeland for the promise of a land under the influence of Christianity.

When Koreans arrived in Hawaii, they were treated like all the other laborers and viewed as a necessary commodity for profit, not as human beings. Faced with low pay and harsh working conditions, at least one thousand Koreans migrated to the United States mainland after they paid back their transportation loan.

In 1905, the Japanese government opposed Korean emigration to Hawaii and stopped it after Korea became a protectorate of Japan. The Japanese government was concerned with the rise of anti-Japanese sentiment and the threat of the Japanese Exclusion Act in the United States. As a major rising power in Asia, Japan demanded equal treatment alongside advanced nations such as England, France, Germany and the United States. To protect its international status as a first-class nation, the Japanese government decided to take action against Korean immigration to Hawaii. It reasoned as follows: (1) the goal was to protect and preserve the international prestige of Japan by eliminating the threat of Japanese exclusion in California; (2) the influx of Japanese workers from Hawaii contributed to the rise of anti-Japanese sentiment and exclusion movements in California; (3) if Koreans could be kept out of Hawaii, the wages of Japanese workers would rise to the point where Japanese laborers in Hawaii would not move to California; therefore, (4) it could achieve its goal by preventing Korean laborers from being brought into Hawaii as strikebreakers.

For these reasons, the number of Korean immigrants (less than 8,000) was much smaller than Chinese (46,000), Filipino (125,000), or Japanese (180,000). Compared with other Asian immigrant groups, Korean immigrants came from a very diverse background. Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino immigrants came from rural and particular geographic areas of Guangdong, China; the Southwestern part of Japan; or Luzon in the Philippines. However, Korean immigrants came from all over the Korean peninsula, and from a combination of both rural and urban backgrounds.

Two distinct characteristics of Korean immigrants were that many converted to the Christian faith and came with relatively high educational backgrounds. Faced with harsh working conditions and low wages, some Koreans were lured to California for higher wages and better working conditions. With the arrival of Korean workers from Hawaii, and later, the arrival of picture brides, the Korean immigrant community on the U.S. mainland began to expand and flourish. Picture brides were women who agreed to marry Korean workers in the United States through the exchange of photographs and background information. Grooms in the U.S. sent photographs of themselves to family members, friends and matchmakers to help them in the selection process.

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.