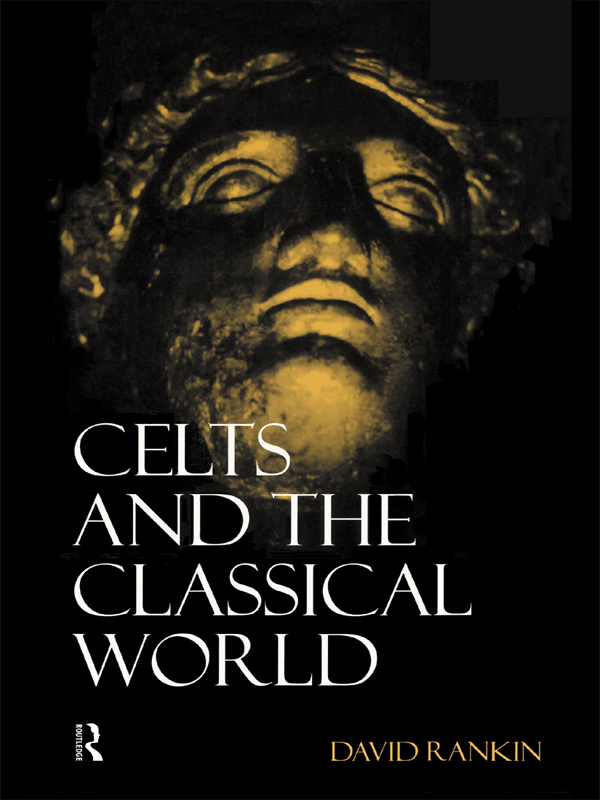

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

1 Origins, Languages and Associations

To observe the Celts through the eyes of the Greeks and Romans is the first aim of this book. We shall scrutinise their perceptions of this powerful and numerous group of peoples, who lived to the north of their Mediterranean world, and who had the inconvenient habit of coming south. In this chapter we shall consider what may be the earliest Classical references to the Celts. We shall try to identify and describe as far as we can within the evidence who and what the Celts were, and what was their origin. Most of our evidence in this and the following chapters comes from the literature of Greece and Rome. The Celts themselves had a lasting prejudice against putting important matters in writing. Not until we reach the eighth century AD, about three centuries after the end of the period which mainly concerns us, do we find insular Celts, not Romanised, but influenced by Rome through Christianity, beginning to set down in writing a literature which was not predominantly Classical in form and content.

Specifically we have to discuss from Greek and Roman points of view some late Bronze Age and Iron Age peoples of Europe who, as far as we may conjecture, spoke dialects of Indo-European origin which are close to what we would now describe as Celtic, and who had a distinctive, but not unique mode of Iron Age culture. Like ourselves, when we talk about the Celtic-descended societies of Wales, Brittany, Cornwall, Man, Scotland and Ireland, the Greeks and Romans had a broad and generally coherent understanding of what they meant by Celtae (Keltoi), Galli and Galatai, even though they occasionally were mistaken about the ethnic affiliations of more remote tribes with whom they had not yet made contact. The word Celt as an ethnic attribute was first used by Greeks to refer to people living to the north of the Greek colony of Massalia (Marseilles) in Southern France. The meaning of the name is obscure. Possible roots are kel exalt or kel strike, as in Latin percello. Another suggestion is kwel turn, Latin incola settler. There are other suggestions. Galli was the name the Romans gave to the tumult of warriors who wrecked their city in 390 BC; it may be connected with other IE words for stranger or enemy such as Latin hostis, Gothic gasts (Stokes 1894:108). The Romans habitually used Galli for all peoples of Celtic language and culture, and it is not known whether it was originally the name of an individual tribe, or a description given by a wandering tribe or tribes to themselves (Whatmough 1970:15). The invaders of Greece and Asia Minor in the third century BC were known to the Greeks as Galatai, which may perhaps have a parallel in Old Irish galdae warlike and galgart a champion. Julius Caesar divides his Gaul into three ethnic regions, by no means culturally or linguistically identical: Celtae, Aquitani, and Belgae (BG I.1), and he mentions many tribal names within these sections which have their individual meanings. Classical writers did not describe the inhabitants of Ireland and Britain as Celts. Nor did the Anglo-Normans or English in later centuries. The name was first used as an embracing ethnic and cultural term in the sixteenth century AD by George Buchanan, and taken up in the seventeenth century AD by Edward Lhuyd (T.G.E.Powell 1958:15). We shall use Celt as a general term, but Gaul, Galli, Galatai, Goidelic, Brythonic, Britanni, Picti (Cruithni), rainn and other specific names will occur from time to time.

Our earliest Greek literary source which mentions Celts is embedded in the text of a late imperial Latin author. Rufus Festus Avienus was proconsul of Africa in 366 AD. He claimed descent from Musonius Rufus, the distinguished and eccentric Stoic philosopher exiled by Nero in 65 AD. Like his famous antecedent, he came from Volsinii in Etruria. His burial inscription proclaims him a successful man, happy in his career, wife and children; proud of his poems, and a worshipper of the Etruscan goddess, Nortia, who not inappropriately was concerned with fortune.

The poem which interests us is his Ora Maritima, a description of the shores of the known world. The first part of this incompletely extant work describes the Atlantic coastline and the coast of the Mediterranean from the Pillars of Hercules to Massalia (Latin: Massilia).

Avienus dedicated his poem to Probus, a consul who may haveheld office in 406 AD. The work is written in iambic verse, and it shows self-conscious, but no doubt, sincere learning. Avienus was a man of education and ability, and we should not be too dismayed by his habit of dropping into his text the names both of famous and of obscure authorities. Amongst others, he mentions Hecataeus, Himilco the Carthaginian, Hellanicus, Scylax of Caryanda, Herodotus, Thucydides, Sallust; also Damastes, Bacorus of Rhodes, and Euctemon of Attica. We cannot tell how deeply read he was in all of these authors. Some of the less distinguished must by this time have been hard to obtain in the original, but he claims (41) to have consulted a great number of writers and to communicate information that has not been available at large. He was a competent writer of verse, but we should be rash to call him a talented poet, even within the restrictions of the didactic genre.

We shall not be incautious, I suggest, if we accept that Avienus is the carrier of some very early information about the Celts in the Classical world. I say this not so much in spite of his pompous and pawky style, as because of it: in concentrating on his own erudite image of himself and grappling with the technical problems of versification, he probably left himself less time for the pure distortion of facts, though we may possibly have to fear some parallax effect inherited from the translators who in some instances came between the Greek originals and his staid iambics.

Avienus description in the second part of his poem of the coastal voyage from the neighbourhood of Tartessus (probably near Cadiz) to Massalia, makes no mention of the Massaliote settlement of Emporiai (Ampurias). From the evidence of pottery which has been found on its site, Emporiai was in being as early as the middle of the sixth century BC (Tierney 1960:1934). It can be argued that if the town had already been founded at the time of the early sailing instructions on which Avienus source is based, it would have been mentioned, and the information would have been conveyed to us by Avienus. The omission, however, may be merely apparent. John Hind has suggested (1972) that Emporiai, which means markets, was the popular name for the place referred to as Pyrene by Avienus, and that this could be the Portus Pyrenaei mentioned by Livy (38.8). However this particular matter stands, it is clear that Avienus had access to a range of ancient materials which themselves embodied information from a very early date.