P ETER B ERRESFORD E LLIS is one of the foremost living authorities on the Celts and the author of many books in the field including The Celtic Empire (1990), Celt and Saxon (1993), Celt and Greek (1997), Celt and Roman (1998) and The Ancient World of the Celts (1998). Under the pseudonym Peter Tremayne he is the author of the bestselling Sister Fidelma murder mysteries set in Ireland in the 7th Century.

Praise for the first edition, The Ancient World of the Celts

An authoritative account.

Irish Times

A truly sumptuous publication... clearly-written.

Elizabeth Sutherland, The Scots Magazine

[A] well-articulated insight into the world of the Celts... If there ever was a truly thorough investigation into the Celts, then this is it.

Adam Phillips, Aberdeen Press & Journal

A timely antidote to the pre-conceptions which have for so long hampered a proper understanding and appreciation of Celtic society.

George Children, 3rd Stone

A splendid new book for fans of all things Celtic, or anyone who wants to know more about how they lived and why they were so successful across Europe.... An excellent book for both reference and enjoyment.

Gail Cooper, Evening Leader

Constable & Robinson Ltd

3 The Lanchesters

162 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 9ER

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in hardback in the UK as The Ancient World of the Celts

by Constable, an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd 1998

This revised paperback edition published by Robinson,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd 2003

Copyright Peter Berresford Ellis 1998, 2003

The right of Peter Berresford Ellis to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in

Publication Data is available from the British Library

ISBN 1-84119-790-4

ISBN 978-1-84119-790-6

eISBN 978-1-47210-794-7

Printed and bound in the EU

10 9 8

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Between pp. 76 and 77

Between pp. 140 and 141

PREFACE

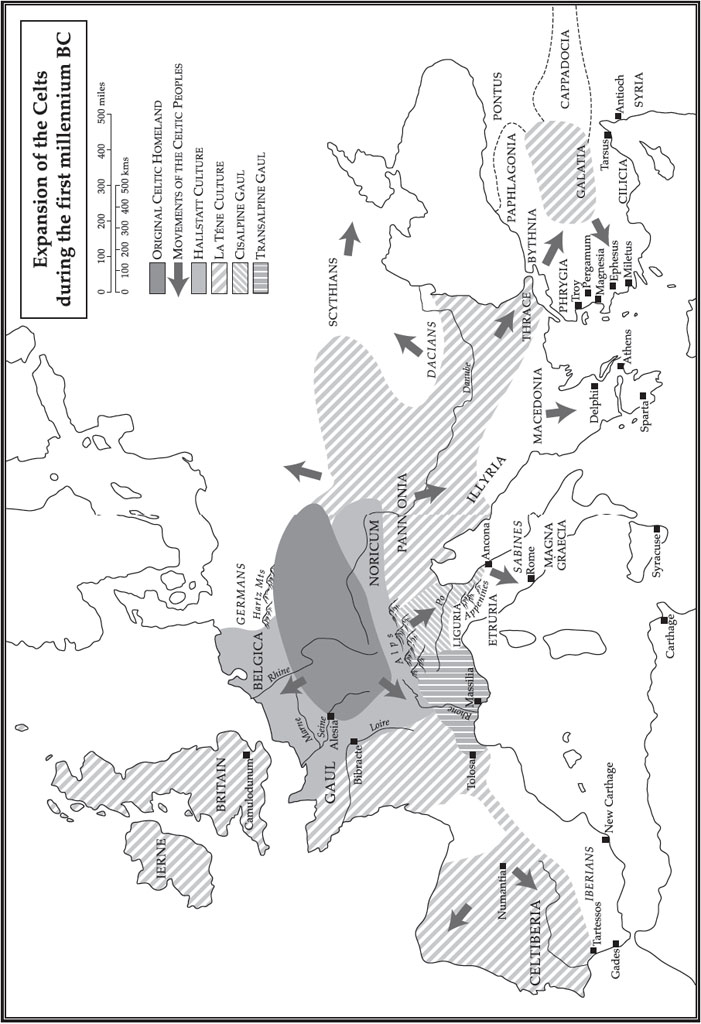

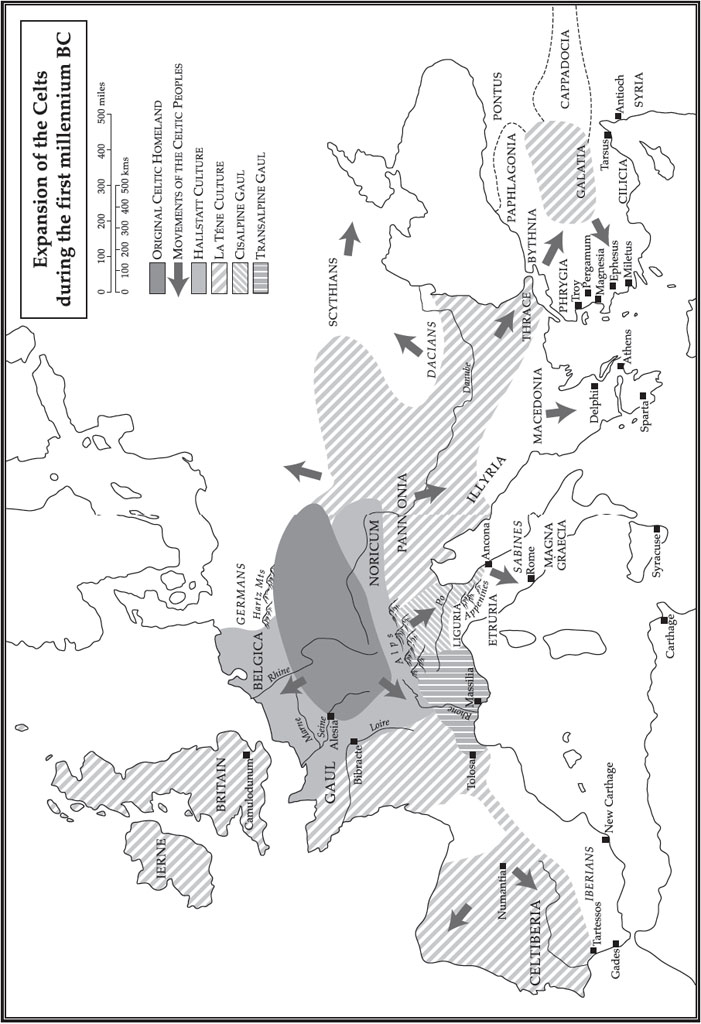

At the start of the first millennium BC , a civilisation which had developed from its Indo-European roots around the headwaters of the Rhine, the Rhne and the Danube suddenly erupted in all directions through Europe. Their advanced use of metalwork, particularly their iron weapons, made them a powerful and irresistible force. Greek merchants, first encountering them in the sixth century BC , called them Keltoi and Galatai. Later, the Romans would echo these names in Celtae, Galatae and Galli. Today we generally identify them as Celts.

The ancient Celts have been described as the first Europeans, the first Transalpine civilisation to emerge into recorded history. At the height of their greatest expansion, by the third century BC , they were spread from Ireland in the west across Europe to the central plain of what is now Turkey in the east; they were settled from Belgium in the north as far south as Cadiz in Spain and across the Alps into the Po valley. They not only spread along the Danube valley but Celtic settlements have been found in southern Poland, in Russia and the Ukraine. Recent evidence has caused some academics to argue that the Celts were also the ancestors of the Tocharian people, an Indo-European group who settled in the Xinjiang province of China, north of Tibet. Tocharian written texts survive from the eighth to ninth centuries AD .

That the Celts left a powerful military impression on the Greeks and Romans there is little doubt. In 475 BC they defeated the armies of the Etruscan empire at Ticino and took control throughout the Po valley; in 390 BC they defeated the Romans and occupied the city for seven months it took Rome fifty years to recover from that devastating disaster; in 279 BC they invaded the Greek peninsula, defeating every Greek army which was sent against them before sacking the Greek holy sanctuary of Delphi and then returning back to the north. Some of them crossed into Asia Minor and established a Celtic kingdom on what is now the central plain of Turkey. So respectful of the Celts fighting ability were the Greeks that they recruited Celtic units into their armies, from Epiros and Syria to the Ptolemy pharaohs of Egypt. Even the fabulous Queen Cleopatra had an lite bodyguard of 300 Celtic warriors which, on her defeat and death, served the equally famous Herod the Great and attended his funeral obsequies in 4 BC . Hannibal used Celtic warriors as the mainstay of his army and, finally, after the conquest of their heartland Gaul, the Celts even served the armies of their arch-enemy, Rome.

Yet warfare was not their only profession. They were basically farmers, engaging in very advanced agricultural techniques whose methods impressed Roman observers. Their medical knowledge was highly sophisticated, particularly in the practice of surgery. As road builders they were also talented and it was the Celts who cut the first roads through the previously impenetrable forests of Europe. Most of the words connected with roads and transport in Latin were, significantly, borrowed from the Celts. As for their art and craftsmanship, in jewellery and design, they have left a breathtaking legacy for Europe. They were undoubtedly the most exuberant of the ancient European visual artists, whose genius is still valued and copied today; their masterpieces in metalwork, monumental stone carvings, glassware and jewellery still provoke countless well-attended exhibitions throughout the world.

Their philosophers and men of learning were highly regarded by the Greeks; many of the Greek Alexandrian school accepted that early Greeks had borrowed from the Celtic philosophers. Even some Romans, who could never forgive the Celts for initially defeating them and occupying Rome, begrudgingly acknowledged their learning. Their advanced calendrical computations, their astronomy and speculation from the stars, also impressed the classical world.

The early Celts were prohibited by their religious precepts from committing their learning to written form in their own language. In spite of this, there remain some 500 textual inscriptions of varying lengths in Celtic languages dating from between the fifth and first centuries BC . The Celts used the alphabets of the Etruscans, Greeks, Phoenicians and Romans to make these records. Moreover, many Celts adopted Greek and Latin as languages in which to achieve literary fame; Caecilius Statius, for example, the chief Roman comic dramatist of the second century BC , was an Insubrean Celtic warrior, taken prisoner and brought to Rome as a slave.

The Celts produced historians, poets, playwrights and philosophers, all writing in Latin. It was not until the Christian period that the Celts felt free enough to write extensively in their own languages and then left an amazing literary wealth with Irish taking its place as the third literary language of Europe, after Greek and Latin. Irish, according to Professor Calvert Watkins of Harvard, contains the oldest vernacular literature of Europe for, he points out, those writing in Latin and Greek were usually writing in a language which was not a

Next page