THE GODS OF

THE CELTS

Dedication

For Stephen: to remind him of chthonic monsters,

ram-horned snakes and famous pigs.

THE GODS OF

THE CELTS

MIRANDA GREEN

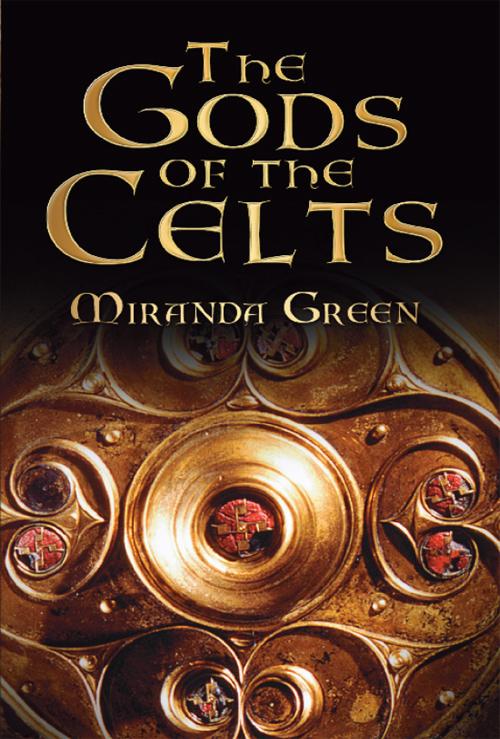

Front cover: The Battersea Shield, Iron Age 350-50 BC (British Museum).

First published in 1986

This edition first published in 2011

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

Miranda Green 1986, 2004, 2011

The right of Miranda Green, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 6811 2

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 6812 9

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I should like to express my gratitude to the following individuals:

Dr Stephen Green, for reading and commenting upon the book in draft and for his constant encouragement and Mrs Sharon Moyle, for typing the first draft of the manuscript. I am grateful for help in providing individual illustrations to John Dent, Archaeology Unit, Humberside County Council; Professor Barry Cunliffe, Institute of Archaeology, Oxford, and Keith Parfitt, Dover Archaeological Group.

I wish to thank the staff of the following museums for their help and for permission to publish their material: Cambridge, University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology; Cardiff, National Museum of Wales; Carlisle Museum; Chester, Grosvenor Museum; Cirencester, Corinium Museum; Colchester and Essex Museum; Dorset County Museum; London, Trustees of the British Museum; Museum of London; Netherhall Collection, Maryport; Newcastle, University Museum of Antiquities; Nottingham University Museum; Peterborough City Museum; Sheffield City Museum; Torquay Museum.

PROLOGUE

Introducing the Celts

The Celts had no tradition of written records and therefore cannot identify themselves to us directly. They are known either archaeologically or through the writing of literate Mediterranean societies. The Celts or Keltoi (in the Greek) were first defined as such by the Greeks before 500 BC. The very earliest reference is in an account of coastal travel from Spain and southern France which is quoted by one Rufus Avienus, proconsul of Africa, in a coastal survey ( Ora Maritima ). Around 500 BC Celts are again mentioned by Hecataeus of Miletus. Some sixty years later, Herodotus in his Histories talked of the source of the Danube being in the territory of the Celts and stated also that these people were almost the most westerly of all Europeans.

The origin of the peoples called Celts by classical writers has long been the subject of speculation and controversy. But it seems irrefutable that somehow, this group of peoples, whose language and material culture contained sufficient unity to be identifiable to their neighbours, had their roots in the later Bronze Age cultures of Europe. However, the Celts whether in Britain or mainland Europe did not suddenly appear from a specific place as the result of a single event but, rather, were people who had become Celtic by accretion in process of time. No one culture or time should be sought as the immediate source of Celtic beginnings. Indeed it could be argued that it is futile to enquire when the Celts first appeared since the people recognised as such by Graeco-Roman authors were in fact the lineal descendants of generations stretching back as far as the Neolithic farmers of the fifthfourth millennium BC. The process of celticisation should thus be seen as a gradual phenomenon. The classical world, as evidenced by its writers, used the term Celts to refer to the barbarian peoples who occupied much of North-West and Central Europe. It should be realised that this term, perhaps carelessly applied (and at times misapplied) was employed to describe a multitude of tribes of differing ethnic traditions and varying customs. Nevertheless, as long as this is understood, it is a useful generalisation. Archaeological research has demonstrated that by the fifth century BC large tracts of Europe from Britain to the Black Sea, and from North Italy and Yugoslavia to Belgium shared a number of elements. By the fourth century BC the Celts were regarded by their Mediterranean neighbours as one of the four great peripheral nations of the known world. Rapid expansion took Celtic tribes into Italy around 400 BC and in 387 Rome itself was defeated. In 279 BC a group of Celts entered Greece and plundered the sacred site of Delphi; in 278 a splinter group established themselves in Asia Minor (Galatia). Whilst it is impossible to speak of a nation of Celts, processes of trade and exchange, folk-movement and convergent evolution, caused the peoples inhabiting barbarian, non-Mediterranean Europe to develop a degree of cultural homogeneity. It was this which was acknowledged by Graeco-Roman authors and which caused them to use Celts as a unifying term. If one speaks entirely archaeologically, it is thus possible to state that Iron Age Celts originated in Central and West Central Europe.

In order to place the Celts in their prehistoric context, it is necessary to look briefly backwards beyond the recognisable emergence of the Celtic world. The later Bronze Age Urnfield culture, commencing circa 1300 BC was roughly coincident with the decline of Mycenaean power. In Central Europe new burial rites may be observed at this time, consisting of large-scale cremation-burial in flat cemeteries (giving rise to the term Urnfield). Their very widespread occurrence around the close of the second millennium BC provides a phenomenon sufficiently coherent for some scholars to equate Urnfield peoples with proto-Celts. This European later Bronze Age is of interest in the present context for two main reasons. One is that the spread of cremation-rites suggests changes in belief about death and the afterlife. Secondly the culture is characterised in material/technological terms by the new ability of bronzesmiths to manipulate bronze into sheets to make such large items as vessels and shields. The vessels were frequently decorated with figural and abstract designs and, along with other paraphernalia, appear to reflect a more mature religious symbolism and more unified methods of religious expression. This prolific sheet-bronze production suggests also both a relatively settled time of prosperous trading and sophisticated organisation of trade-routes. The use of sheet metal vessels (sometimes mounted on wagons) in religious ritual is interesting for, by about 12001100 BC, we know that wetter conditions prevailed and it is suggested that this climatic change may be reflected in the water-cults possibly represented by such containers.