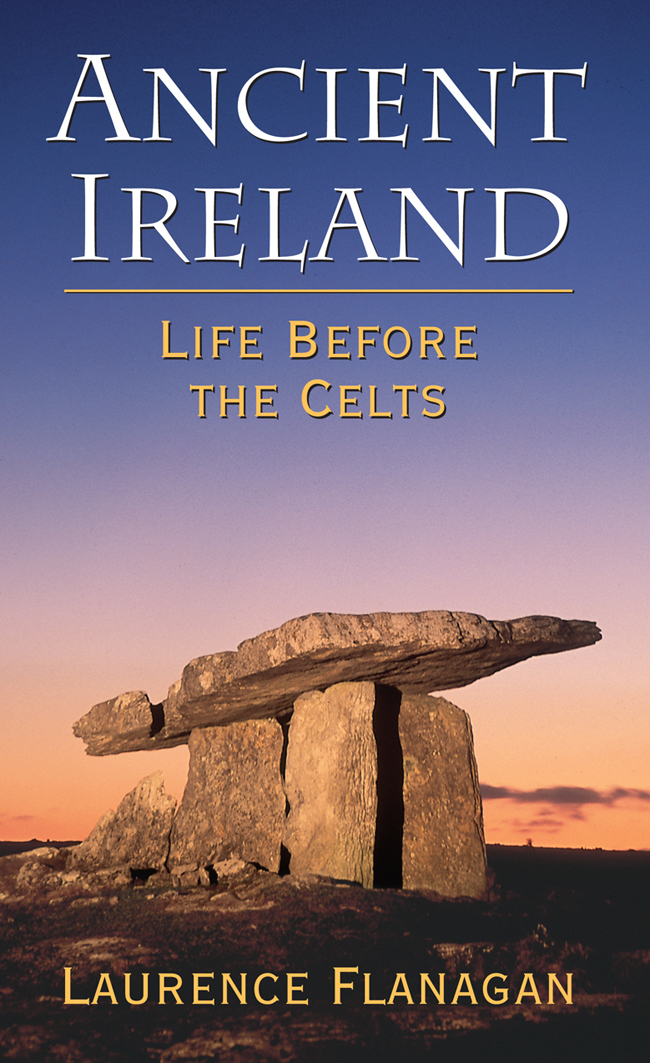

ANCIENT IRELAND

LIFE BEFORE THE CELTS

Laurence Flanagan

Gill & Macmillan

CONTENTS

PART 1

THE ARCHAEOLOGY

INTRODUCTION

T he discipline that helps us to recognise the artefacts, monuments and events in an Ireland that was not merely pre-Christian but was fairly certainly pre-Celtic as well is archaeology.

Many years ago a young, possibly slightly arrogantcertainly self-confidentarchaeologist defined archaeology as the study of social and economic history through the actual commerciable products of societyor in other words the story of Mans attempts to keep the wolf from the door by means of better doors and better wolf-traps. Thirty years later I doubt if I would change a word of that definition, except by pointing out that commerciable products includes not only the obvious, such as food, tools, and housing, but also things like tombs and temples, which, even if they have no resale value, have certainly incurred costs in the form of time, labour, and energy.

It is necessary always to remember that although the flint tools, pots, tombs, house plans and decoration so frequently illustrated in archaeological text-books are important, they are important primarily as documents of social historyas clues to how their makers and users eked out a precarious living or enjoyed a lavish life-style. In a photograph of a funerary pot containing the cremated bones of what once was a human being, it is the cremated bones that are vitally important, not the pot: it is primarily important as a sort of fingerprint of the deceased, providing clues about who or what he or she was, how they might have lived, and, finally, how they might have ended up inside it.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

Despite the importance of the human being, whether cremated and inside a pot or notsince, as far as we are concerned, prehistoric humans are totally mute and have left no record of their feelings or of their attitudes to life or death or to their fellow-humanswe have to resort to physical evidence that has survived. Essentially this leaves us with the objects they madethe tools, the ornament, the houses, the tombs, reflecting different aspects of their life. In addition, of course, we have the testimony of natural historythe geology, the zoology, the botany, the biology, the pathology, even the physicsthat cast light on their environment and their condition.

Genetics

Unlike the inferences drawn from ethno-archaeological parallels, the laws of genetics are normative and inflexible. They determine whether a population is large enough to survive in a healthy condition or whether it is too small to avoid extinctionand they apply both to human beings and to animals, whether domesticated or wild. The influence exerted by genetics on an isolated island colonised by humans for the first time is considerable, even if, in the past, it has not been considered sufficiently or considered deeply enough. Estimates of population sizes have to be considered with regard to the viability of genetic poolsboth for humans and for animals, especially the animals that were introduced by humans to form the basis of their nutrition. The endangered species is not a modern invention, though the concept may be.

Genetics, however, is not all bad news for archaeologists. One of the slightly depressing features of prehistory is that we know the names of none of the people whose bones we may be examining, or merely handling, or whose potmade by them, or merely used by themwe may be examining for any shreds of information about its maker or user. We can never obtain photographs of them, or recordings of their voices. If, however, DNA fingerprinting was applied in the cause of archaeology we could achieve a much closer relationship with them: we could know, for instance, whether we were related to themor that it is simply impossible for us to be. We could establish whether two people sharing a grave were related, or merely good friends. In a manner of speaking, it would make them into more real human beings.

Unpredictability

One of the quirks of archaeology is its inherent unpredictability. An archaeologist could today make a reasonably confident statement, Nocopper or bronze nails were definitely not used in the construction of buildings in the Bronze Age in Ireland, and be proved wrong tomorrow. For many years the lack of evidence of beakers in the southwest of Ireland, where the plenteous supplies of copper are found, has been a dilemma for those who thought that the makers of beaker potterythe Beaker Peoplewere, notwithstanding this, the most likely people to have introduced metallurgy to Ireland. The recent and unpredictedthough not, in some ways, unpredictablediscovery of the site at Ross Island, County Kerry, with its beaker pottery, its association with copper smelting and its favourable radiocarbon dates has changed all that. Negative evidence is not a very faithful colleague.

In a manner of speaking, the fact that humankind itself is unpredictable is the quintessential stumbling-block for archaeologists. We have to assume that the people whose dwelling-places, artefacts, lives even, we are dealing with were rational, integrated, sane and sensible human beings. Then we look around at our own contemporaries and wonder how this belief can possibly be sustained.

Non-technical and non-practical traits and activities

It is probably inevitable that right from the beginning of the human occupation of Ireland many activities were rife of which we have now no directthat is, archaeologicalevidence. It would seem, from a perspective of modern, and not so modern, society, that sport or games of some sort or other would have been prevalent, even if at Mount Sandel only five-a-side could have competed in the football tournament, kicking the inflated bladder of a pig. Running races would surely have been a popular pastime, right from earliest timesif only because it would have provided fitness and fleetness for the hunt. Perhaps with the introduction of the horse by Beaker People, horse-racing could have become established in Ireland. Religion, of course, in some form or another, was clearly established in the Later Stone Age or Neolithic Period. Court tombs clearly indicate a desire to erect monuments to dead ancestors; perhaps we have not yet discovered a Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) precursor. Passage tombs seem not merely to be an expression of some form of religious belief but, much more than court tombs, of a sort of social supremacy. These innocent-seeming activities might of course have witnessed the beginnings of their ultimate opponents: did the matches between Mount Sandel United and Lough Boora Rovers attract football hooligans? Did the rival religious groups burn each others temples? Fortunately, perhaps, archaeology in Ireland does not (or has so far failed to) reveal this kind of truth. The true believer, however, is aware that one of these days it might.

ARTEFACTS INTO ARCHAEOLOGY

The landscape of prehistory is littered with artefacts, as, indeed, is the landscape of Ireland. There are many kinds of portable artefact, made of such varied materials as flint, stone, wood, leather, textiles, bronze, and gold. There are many kinds of non-portable artefact: monuments of various kinds, reflecting different needs on the part of the prehistoric inhabitants, showing different sizes, styles and degrees of complexity and made of materials such as wood or stonethough it is those made of stone that are most likely to have survived. At this stage, however, they are simply dissociated artefacts and reveal little about their makers and users, except, perhaps, that they had a need for different types of artefact for different purposes and that their makers had certain skills in the making of tools or implements of various materials. How do we persuade them to tell their stories?