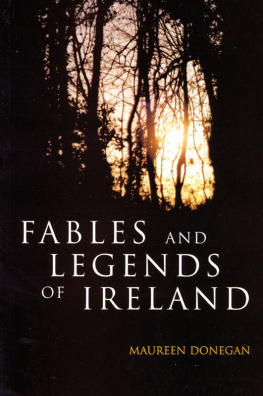

I reland is an island of stories, some of which stretch back over many centuries and have their roots in a tradition that goes back even further. Many of these legends have close associations with particular places. This book retells just some of these legends and links them with the places from which they grew. Place and story are inextricably bound together, and so in the arrangement of the stories I have followed a geographical sequence rather than the traditional division into four cycles.

However, these traditional divisions do provide a useful context in which to gain a sense of the richness of the world of the Celtic legends. The first of these, the Mythological Cycle, tells the tale of the very origins of human life in Ireland. The stories deal with the successive invasions of the island, the great battles between the tribes of the Tuatha D Danann (the divine people of the goddess Danu) and the Fomorians, the demonic tribe who competed with them for control of Ireland. They also include the stories of the Sdh (those mythical beings which share human passions but not human sickness and age), such as that of the lovers Midhir and tan. The second cycle is the Ulster Cycle, which has at its heart the great epic of the Tin B Cuailgne, (The Cattle Raid of Cooley). The central story of the battle between Conchobhar, king of Ulster, and Maeve, queen of Connacht, encompasses the exploits of the great hero, C Chulainn. This cycle includes associated stories such as that of Deirdre. There has been much dispute between scholars about the period in which the Ulster Cycle is set. Conchobhar, King of Ulster, was said to have lived in the first century AD , and the nature of the society portrayed warrior-like and tribal seems close to our perceptions of the Celtic Iron Age. But Maeve, for example, has her roots as a goddess figure much further back in time, as do many of the figures woven into the tapestry of the stories. Similar uncertainty surrounds the stories of the Fianna Cycle. These stories deal with Fionn and his hunter companions, including the epic pursuit of Diarmuid and Grinne. The Fianna Cycle stories take place in the natural world rather than in the courts of the kings, and the fian actually existed as a group of young warriors who lived in small groups outside society. The stories are set at the time of Cormac Mac Airt, who was said to have reigned as high king in the third century AD , but the genesis of the figure of Fionn is probably far older than this. The fourth cycle, known as the Historical Cycle or the Cycle of the Kings, has its stories set in a later period, and some of the characters involved are based on actual historical characters living in a Christian society. However, here, as in all the legends, different worlds and different periods intertwine and historical characters drift in and out of the landscape of legend. It is impossible to establish a clear and consistent chronology, all the more so as the stories were written down many centuries after they had already had a long history as part of an oral tradition. This oral tradition indicates that while extant texts date from no earlier than the eleventh and twelfth centuries, many of the stories were originally written down up to four centuries earlier. The Ulster Cycle tales may have been written down as early as the seventh century and they portray a world that is undeniably pre-Christian in its ethos. Irish literature is the earliest vernacular literature in western Europe and, while scholars have argued over the historical existence of its heroes, and queens and kings, whatever human existence these characters may have had has long been concealed under the layers of a thousand re-tellings. I therefore make no apologies for telling these stories once again in contemporary language, or for the slight liberties I have taken with some of the texts. Every society retells its myths in a slightly different form and the texts we have of the tales are the products of a medieval Christian society where the stories were recorded by clerics who added their own gloss to the versions they wrote.

Having said this, I must add that the amount of loving effort the scribes put into producing and preserving these beautiful manuscripts indicates how important these stories were to their society. And through all their re-tellings the stories retain a distinctive sense of the sacredness of the natural, sensual world; they celebrate it in its entirety, from the joy of the blackbirds song in spring to the cold beauty of winter. St Colmcille is said to have been more frightened by the sound of the axe in his beloved oak grove at Derry than of death and hell, and early Irish lyrics, many written by monks, include many lovely celebrations of the natural world. This close connection with the natural world and with the features of the landscape is also found in the poems of the