ALISTAIR MOFFAT was born and bred in the Scottish Border country. A former Director of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and Director of Programmes at Scottish Television, he now runs the burgeoning Borders Book Festival. His also runs a production company based near Selkirk and has written twelve books, including Kelsae, The Borders and The Reivers, all of which are published by Birlinn.

This eBook edition published in 2011 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2002 by HarperCollins Publishers

This edition first published in 2007 by Birlinn Limited

Copyright Alistair Moffat 2001, 2008

The moral right of Alistair Moffat to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted

by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in

any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-116-3

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Donnie Campbell was a passionate football fan. In his office at Sabhal Mor Ostaig, the Gaelic-medium further education college on the Isle of Skye, a small television was showing Scotland playing in a World Cup qualifier in the late 1980s. With his eyes constantly flicking to the screen, Donnie was trying to concentrate on talking to me in English about something or other, but when Scotland scored a goal, he immediately leaped up and roared. A steach! Its in!

In extremis, even exultation, Gaelic sprang first to his lips. It occurred to me that for some people, albeit a rapidly diminishing number, Gaelic was not simply a colourful facet of Scots culture, but still existed as an entirely different way of seeing Scotland, of understanding our national identity and even of coping with, the continuing tragedy of our football team. In his gentle and straightforward manner Donnie told me a great deal about Gaelic, about the West, and the links with Ireland and the south. His early death in a car accident was a sore loss and I am glad to remember him and his quiet kindness, and acknowledge both. Moran taing a charaid.

Christeen Combe taught me Gaelic and had immense patience with my impatience. She not only guided me successfully through public examinations, but in introducing me to her family also offered an unselfconscious means of understanding better the Gaelic speech community of the Western Isles. Christines teaching was translated into practical use by Rhoda Macdonald, who insisted that we speak Gaelic at work in Scottish Television and who lent me books, tapes and insights. Through talking to Rhoda I began to see that Gaelic Scotland had much in common with Ireland, Man, Wales and Cornwall, and that some of this sonorous talk about culture hides a great deal of fun and laughter.

Like the good teacher he is, Norman Gillies, the principal of Sabhal Mor Ostaig, has always encouraged my interests. When the college began to create links with Ireland and Irish Gaelic speakers, it began to seem less like an outpost on the edge of Scotland and more like a cultural entrepot in the middle of the Celtic west. Norman will find the arguments in this book very familiar.

When we came to film a ten-part series of The Sea Kingdoms for Scottish Television I had to rethink the book as spoken words and moving pictures. My director, Anne Buckland, demanded clarity and endless rewrites some of which have found their way into the book. She may even have stamped her foot once or twice. John Agnew, Ken MacNeill, Anita Cox and Adam Moffat helped greatly to make our long journey from Stornoway to Penzance a creative one.

At HarperCollins Michael Fishwick and Arabella Pike created the means for me to write this book and I am grateful for their faith in it. To Kate Morris fell the unenviable task of editing the text and managing it through to publication. Because of her hard work, diligence and tact, The Sea Kingdoms is undoubtedly a better book.

It is simply a pleasure to work with David Godwin, my agent, a lovely man with a sharp eye for a good project and a softly spoken word for an agitated author. Thank you David.

Finally, I want to thank the scores of people who stopped what they were doing, took the time and sat down to talk to me in Scotland, Ireland, Man, Wales and Cornwall. It was grand.

MAPS

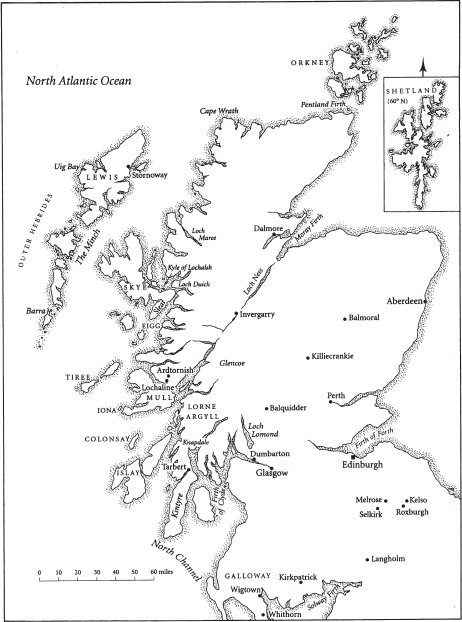

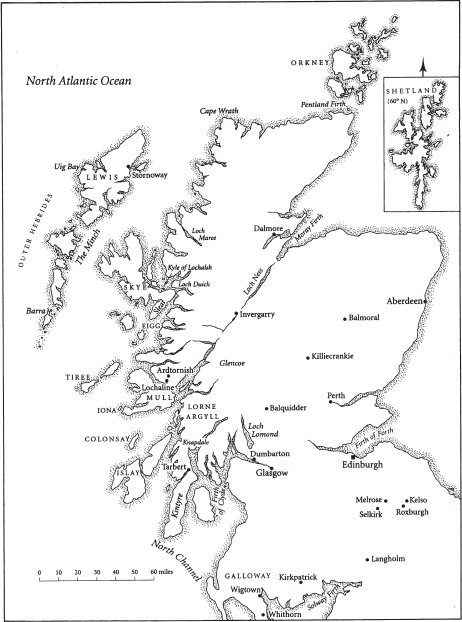

Scotland

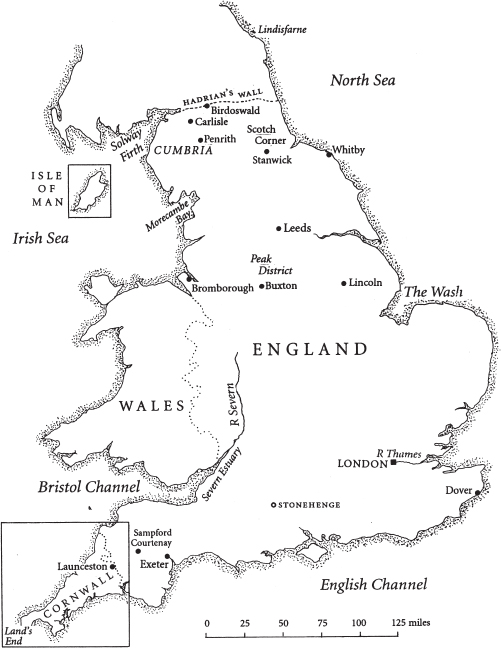

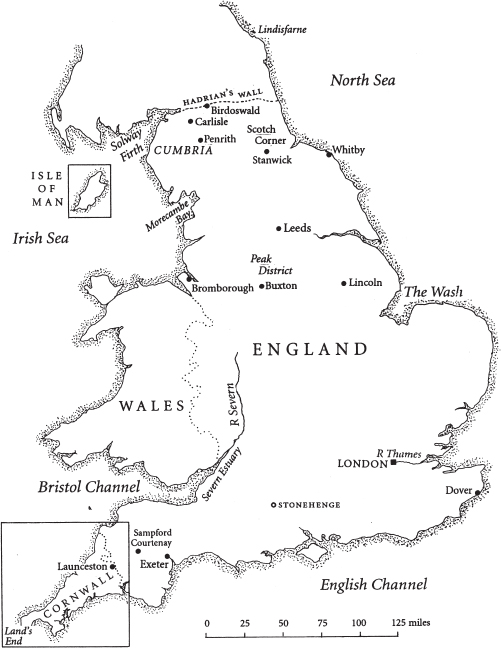

England

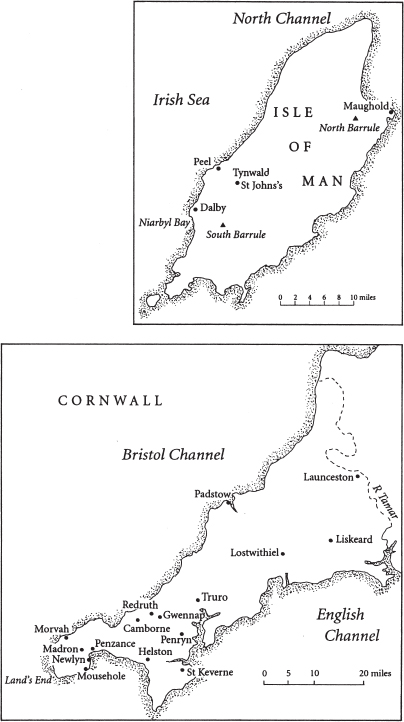

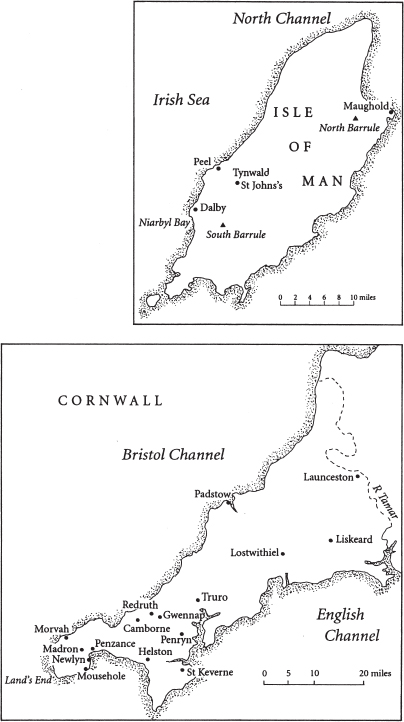

Isle of Man and Cornwall

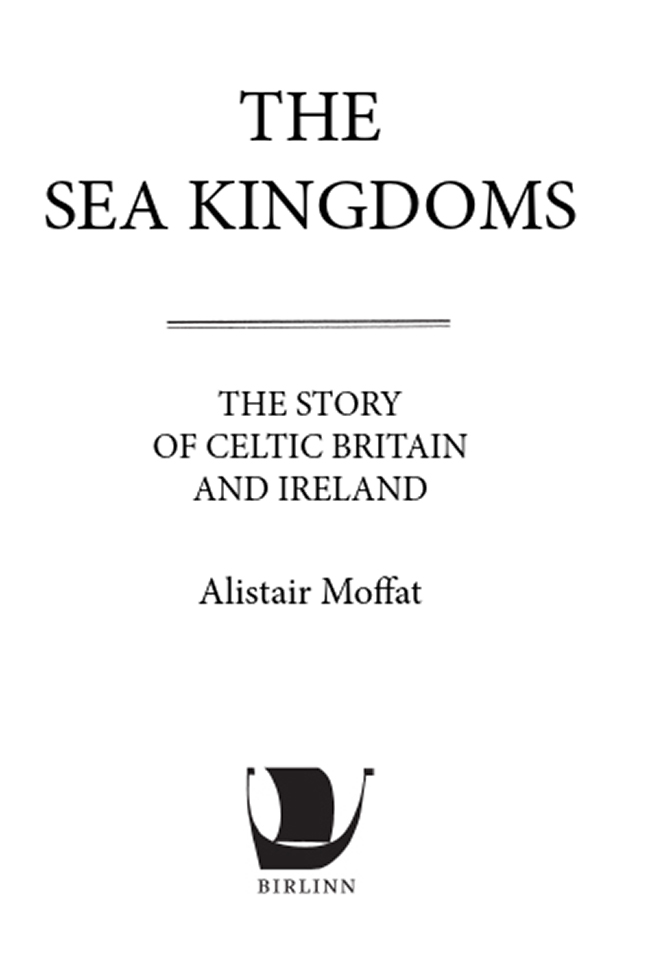

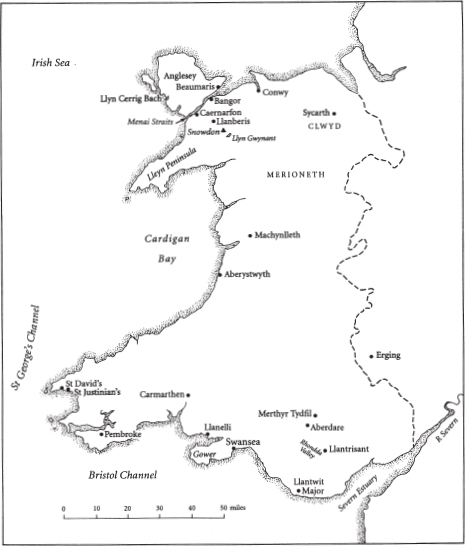

Wales

ONE

The Music of the Thing

As It Happened

THIS IS A HISTORY of whispers and forgetfulness, a story of how the memories and understandings of the Celtic peoples of Britain and Ireland almost faded into inconsequence. It is also a story of the struggle for control of these islands, of those who lost it, and how they continued to interact with the eventual winners, the English and the British. It attempts a lengthy definition of what it means and meant to be Celtic, to think and behave in ways that are different from the British habits of mind and also often different from the simply Welsh, Irish, Scots, Manx, Cornish and English traditions. With the creation of parliaments in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, it is timely to draw up a catalogue of cultural difference, a list of half-forgotten reasons for some of the tensions which have led to the break-up of Britain, the creation of a new and evolving union between England and her old Celtic colonies, and new relationships between those regions.

Two thousand years ago these tensions lay in the future. The farms, fortresses and harbours of these islands echoed to the speech of Celts who recited their history, managed their politics and conducted their business in recognizable versions of old Welsh and early Gaelic. Over the face of England and parts of lowland Scotland where the old Welsh language has long fled, ancient place names evoke those people who first described the rivers, lakes, mountains and marshlands of Britain. Another history of these islands, a Celtic history, often unclear but just catchable, can be heard in the quiet words and phrases of Welsh and Gaelic. For language is the most important yet elusive definition of what Celtic meant then and means now: it is a matter of understanding and listening, and is certainly not a question of race or place of birth. First and foremost, the Celts of Britain are a speech community. At the time when an older version of Welsh was spoken over much of the island of Britain, Irish was the common tongue from Belfast Lough to Bantry Bay: Irish Gaelic and Welsh are cousin languages, sharing syntax and vocabulary, although over time they have become mutually unintelligible.