The British

A GENETIC JOURNEY

This eBook edition published in 2013 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Alistair Moffat 2013

The moral right of Alistair Moffat to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-78027-075-3

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-567-3

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

List of Illustrations

Preface

W HEN H ERODOTUS of Halicarnassus wrote history in the fifth century BC , he intended it to be something like an investigation, the collation of statements about events, people and circumstances made by those who had been there and seen them. Like a detective, he was pursuing enquiries. In Greek, history meant something like testimony. Soldiers who fought in battles, travellers who had seen Nile crocodiles, supplicants who had bowed before Persian kings they were the sorts of people Herodotus wanted to hear from. But as timelines lengthened and perspectives shifted, historians inevitably came to depend on more distant sources, usually the written records of what witnesses or the actors in important episodes said about them. And for many centuries, most of the writing in Britain was done by clerics who were chroniclers often far removed from the action, rarely actual witnesses. Into the modern period archaeology came to supplement the patchy survival of documentary records, and for the long millennia before Herodotus and the statements of witnesses, what could be excavated and reconstructed became virtually the only source of reliable information. Without the patience, skill and imagination of generations of archaeologists, our prehistory would amount to little more than a set of assumptions and guesses.

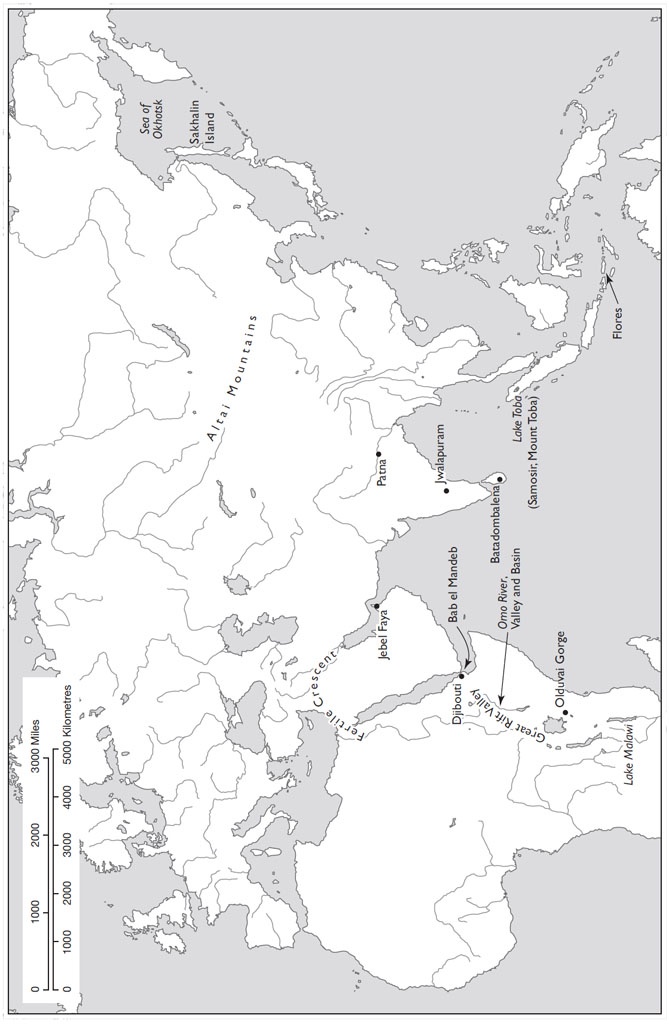

Recently, population genetics and in particular the study of ancestral DNA have added an entirely new dimension to our understanding of our past. The ability of scientists to identify the origins and dates of DNA markers and to use them to track the movement of people across the Earth has been revealing, sometimes startling. The dim and very distant prehistoric past can come brilliantly and movingly alive when the passage of a marker is traced from Manchuria and the shores of the Yellow Sea in the North Pacific clear across the Eurasian landmass to be found in Edinburgh in 2013.

For many millennia the last ice age held Britain and much of the northern hemisphere in its sterile, savage grip. In the brilliant white landscape of the ice-domes, frozen mountains a kilometre thick where incessant hurricanes whipped around their flanks, nothing and no one could survive. That brute fact made Britain a clean slate, a place waiting for its people and their DNA to come. When temperatures at last began to rise, the glaciers rumbled, groaned, splintered and cracked, and the land greened once more, people returned. These pioneers, the first of our species to see the rivers, the grasslands, the forest canopy and the hills and mountains that had been sleeping under the ice-sheets, are amongst our earliest ancestors. They may seem like another race, but DNA confirms an unbroken link. And when the last of the ice had gone, more people came north to hunt and gather in the wildwood, to fish and forage on the seashore, and to begin Britain.

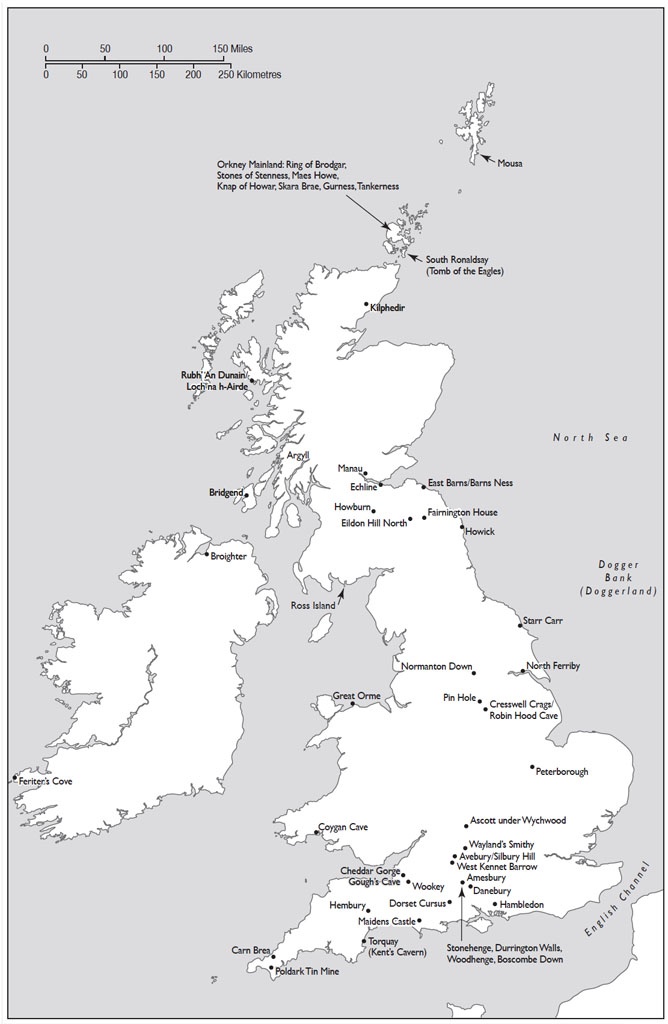

Over thousands of years of prehistory, our ancestors walked to the farthest north-west of the Eurasian continent. DNA maps their movement and can approximately date their arrival. For at least four millennia after the ice, Britain was a peninsula and our people could make their journeys dry-shod. The landscape they entered was virgin. The ice had swept all life out of Britain and after c 9000 BC the land waited for the hesitant tread of the earliest pioneers. That simple fact makes our islands the sum of many migrations, a destination at the farthest north-west reach of Europe for many genetic journeys. A nation of immigrants on the edge of beyond.

All human beings, indeed all living organisms, have DNA, and that means something unarguable: we are all part of history. When Herodotus witnesses reported, they tended to remember the doings of the great or the mighty, kings, queens, warriors, battles and politics. But DNA makes us all witnesses, everyone who lives in Britain. Neither spectators nor the crowd barely discernible in the dimly lit background, we are every one of us actors in the unfolding drama of our history.

The Irish Sea Glacier

One of the most striking images in studies of the last ice age is what some scientists believe should be called the Irish Sea Glacier. They believe that it rumbled for 700 kilometres from its source in the ice caps of Scotland and Ireland and then squeezed between higher glaciated land either side of the North Channel. It pressed on the northern coasts of Cornwall and the Scilly Isles. It is even conjectured that the glacier continued to flow south even when parts of south Wales, the Bristol Channel and the coasts of south-west England were ice-free. It was a kind of valley-glacier of the sort seen in the Himalayas. Others disagree that such a glacier ever existed, but the value of such speculation is that it forces us to visualise how different familiar landscapes and coastlines were in the deep past.

The past is a foreign country, they do things differently there, was the opening sentence of L.P. Hartleys The Go-Between, and it is apposite in considering the mysteries of our prehistory. Human sacrifice, cannibalism and the decapitation of children are all abhorrent practices now, but they were part of the experience of our direct ancestors, people whose DNA many of us carry. Fragments of their lives, like the unmade pieces of an archaeological jigsaw, lie around us on every side and as we try to make a clearer picture of the ranges and camps of hunter-gatherers, the great timber halls of the early farmers and the rituals that took place inside the stone circles, we must never fall into the trap of thinking of our ancestors as foreign. As Hartley wrote, the past is foreign, but its people were our people and their story is seamless, part of our story.

The balance of this book is heavily skewed to our prehistory for the excellent reason that the nine millennia before written record form the overwhelming proportion of our history. The early immigrations occurred before the brief visit of the Romans in the first century BC , and it is in tracing these that DNA studies can be most illuminating. But there is also a good deal to say about the first millennium AD . DNA can shine a light on what used to be known as the Dark Ages, the time of the Anglo-Saxons, the Vikings and other Northmen. After 1066, the picture stabilises as significantly fewer new people came and settled.