Contents

Guide

Alistair Moffat was born and bred in the Scottish Borders and studied at the universities of St Andrews, Edinburgh and London. A former Director of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, Director of Programmes at Scottish Television and founder of the Borders Book Festival, he is also the author of a number of highly acclaimed books. From 2011 to 2014 he was Rector of the University of St Andrews.

This edition published in 2019 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Alistair Moffat 2013, 2017, 2019

First published in hardback in 2013 as

The British: A Genetic Journey

The moral right of Alistair Moffat to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78885 230 2

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Iolaire Typesetting, Newtonmore

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Contents

List of Illustrations

James D. Watson and Francis Crick with their model of the DNA molecule

Maurice Wilkins

Rosalind Franklin

Francis Cricks original sketch of the double helix

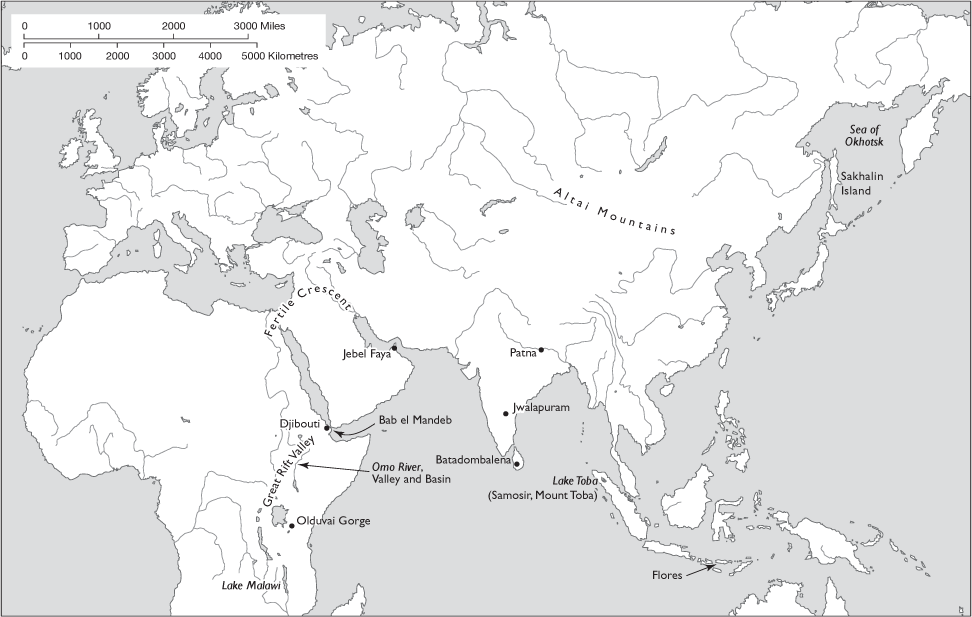

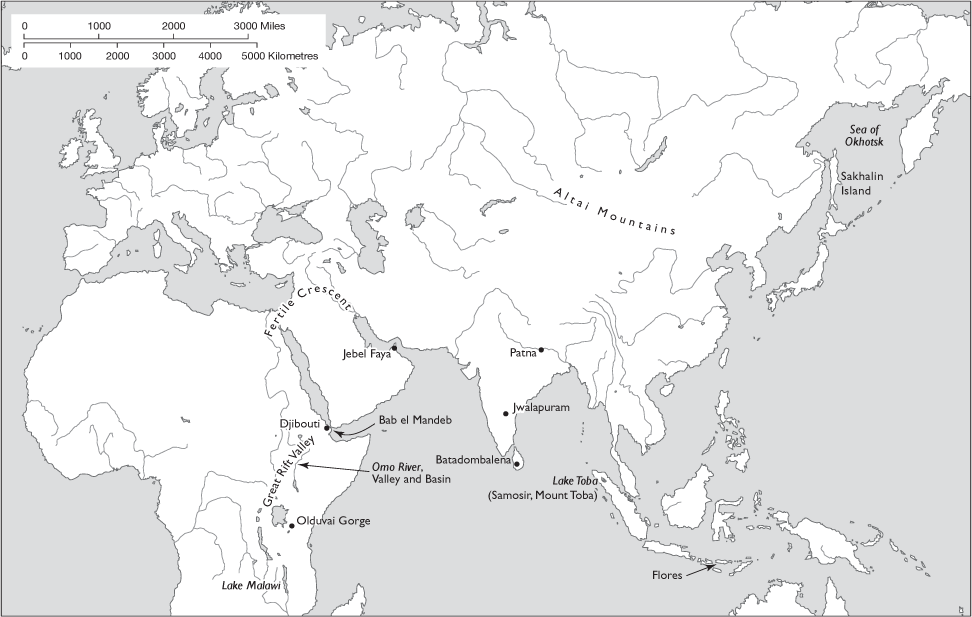

The Great Rift Valley of Tanzania

The Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania

Louis Leakey measures the fossil-bearing strata in the Olduvai Gorge

Richard Leakey

Excavations in the Denisova Cave

What Neanderthal men looked like

The famous 15th-century map showing Vinland

Horses, cattle and rhinoceros depicted at Chauvet Cave

What Cheddar Man may have looked like

The Ring of Brodgar, the Ness of Brodgar, the Stones of Stenness and Barnhouse

The Stones of Stenness

Stonehenge

The Amesbury Archer and his grave goods

Jacob Grimm

Eildon Hill North, showing the hut circles near the summit

A reconstruction of part of Hadrians Wall

William the Bastard as he stepped ashore to become the Conqueror

Grubbing for edible potatoes in the Irish Famine

The Venerable Bede

Mousa Broch, Shetland

Maiden Castle in Dorset

Boudicca foments bloody rebellion

Offas Dyke

Jewish immigrants arriving in early 20th-century London

Enoch Powell

Examining a DNA sequence

Preface

E VERYONE THINKS THEY are different and that the families, groups or communities they belong to are distinctive. Usually expressed in Scots, there is a ringing, defiant, splendid phrase: Whos like us? Damned few, and theyre all dead! Some communities have a serious claim to be more different than others, and in Scotland the Gaelic speakers of the Highlands and Islands have a robust and historically undeniable reason to think of themselves as standing apart. After all, they use a different language. Language shapes conceptual thought, even forms attitudes, and the Gaelic speech community certainly seems to me to add richness to Britains diversity. A tiny group, perhaps only 58,000 strong, they have historically looked at our country from the periphery, offering a different and sometimes illuminating and sobering perspective.

So that I could understand something of these attitudes and how they were formed and expressed, I decided 30 years ago to learn their language. I even sat public examinations, although that was not an entirely positive experience. I gained only a B at Higher Gaelic (Learners) though it could have been an A but for a disaster. Having been taught by a native speaker of Lewis Gaelic, I could not understand clearly the Mull accent of the lady who read the listening comprehension paper. To make matters worse, just as she began, a fuel tanker pulled up outside. When I told her (in Gaelic) that I could not hear her, she refused to read the passage again. But subsequently my command of the language did improve a little as I inflicted what I had learned on any passing native speaker who had the patience to indulge me.

At that time I worked at Scottish Television and was responsible amongst other things for commissioning programmes in Gaelic, and I wanted at least to grasp the gist of what was being said on screen. It was also a busy period the moment when the government unexpectedly began to fund the production of more Gaelic television, and it seemed absurd to me that I could not understand the language.

Many years later my interest in cultural and historical differences in Britain was caught when I watched a TV series called The Blood of the Vikings. In particular I was very impressed and intrigued by the contribution of a young geneticist, Dr Jim Wilson, from University College, London. In a study of the ancestral DNA of populations of men in Orkney, he had been able to identify a very significant Viking component. From testing a large sample, Jim had discovered what seemed to me to be a series of startling statistics.

Analysis of the Y chromosome, which is passed on only through men, allows geneticists to trace fatherlines far back into the deep past, well beyond the reach of written records. In Orkney between 20% and 25% of men carry a DNA marker known as M17, the origins of which are in Norway, where around 30% of the male population carry it. M17 was therefore a very likely candidate for a distinctive Viking genetic signal. If it was, then this marker should be even more prominent in the Y chromosome lineages of men who have distinctive Orcadian surnames: along with their Y chromosome, men usually inherit their surnames from their fathers.

When Jim tested the DNA of men with characteristic Orcadian surnames such as Clouston, Rendall, Flett, Foubister and Isbister, it turned out that an astonishing 35% had the M17 marker or another signature predicted to be Norse in origin. These men were undoubtedly descendants of the Vikings who began to settle in Orkney after the 840s.

Wondering if his methods could be applied to the Gaelic speech community that lived on the Atlantic seaboard, I contacted Jim and we met near his home in Linlithgow. We began work on a series for the Gaelic television service and decided to call it Air a Chuan (On the Ocean). Three communities and various families were selected and DNA testing began. Some months later we filmed a series of interviews when results were revealed to the men who had given samples of their saliva. It was a fascinating and surprising process. There were indeed Y chromosome markers that were much more common in the Hebrides and along the shores of north-western Scotland and Ireland than in the rest of the country. Some of them might reasonably be thought of as Celtic.