This eBook edition published in 2014 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Alistair Moffat 2014

The moral right of Alistair Moffat to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78027 229 0

eBook ISBN: 978 0 85790 807 0

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

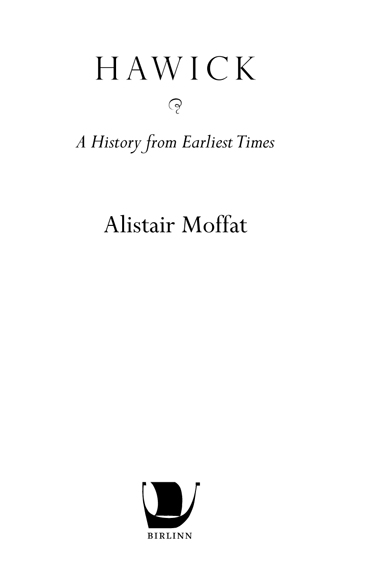

The Mote, photographed in 1912

Auld Mid Raw, demolished in1884

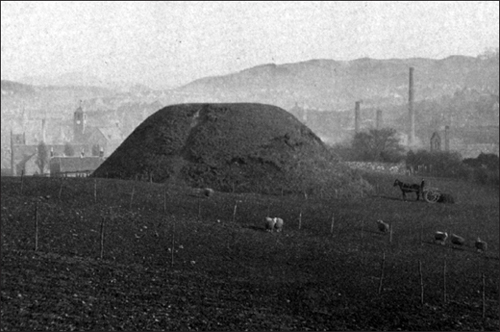

Hawick Common Riding, 1902, led by Cornet William N. Graham

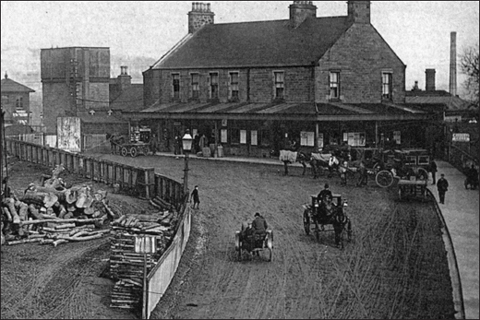

Hawick Railway Station, 1903

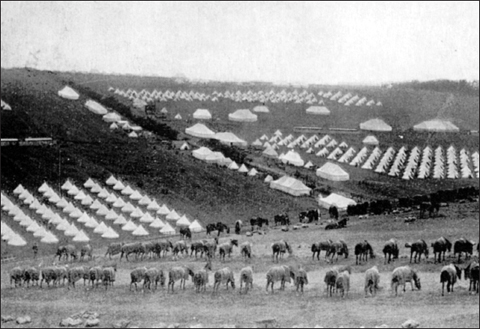

A cavalry regiment at Stobs Camp, 1904

Stobs Camp Post Office and a group of regimental postmen, 1905

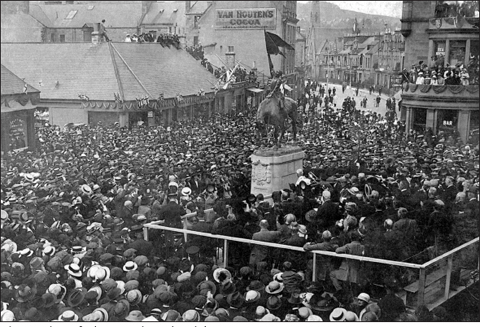

The unveiling of The Horse by Lady Sybil Scott in June 1914

The 400th anniversary celebrations of Hornshole in 1914 at the Volunteer Park

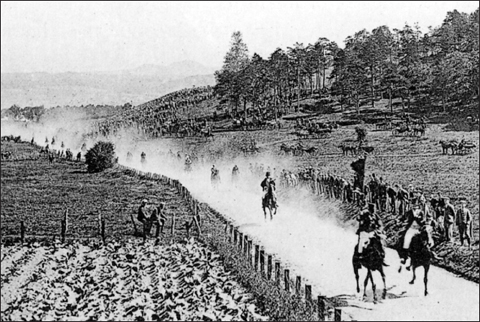

The Chase

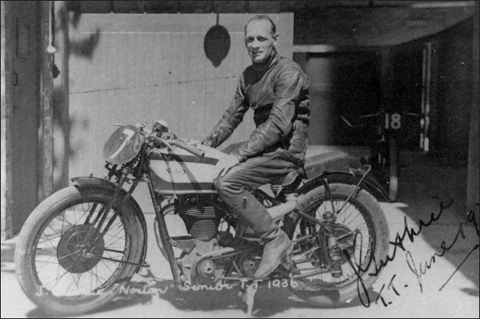

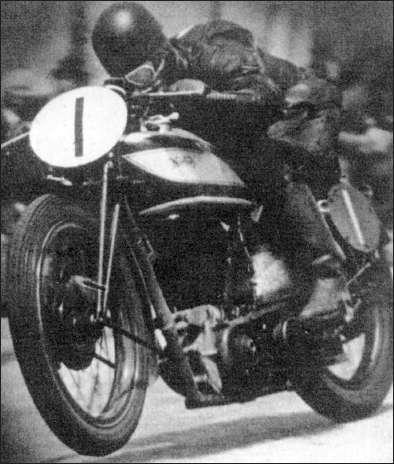

An autographed portrait of the great Jimmy Guthrie

Manly support made in Hawick

Jimmy Guthries characteristic riding style

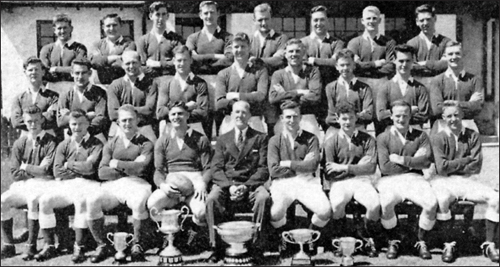

Jack Anderson, Hawick and Scotland, Huddersfield and Great Britain

Hawick RFC, Border and Scottish Champions, 195960

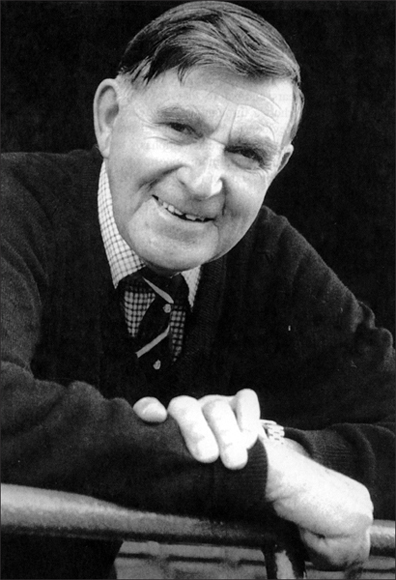

Bill McLaren

INTRODUCTION

THE IRVINES

A YE DEFEND !

Startled, I looked up at my mum in terrified astonishment.

Aye defend your rights and Common! she shouted as the Cornet raised up the banner and the High Street crowd roared its support.

My mum never shouted at home in Kelso not even when she had cause, usually supplied by me. A gigantic, snorting horse suddenly clattered sideways and I skittered behind her. But she cheered all the more and muffled, from somewhere, I could hear, Hip, hip, hooray! Hip, hip, hooray! Hip, hip, hooray! The riders and the flag moved on, the crowd followed and I stopped clutching my mums hand so tightly.

When she came home to Hawick for the Common Riding, my mum became a different person. Although I did not understand it at the time, she came home every summer to be herself again a Teri (a native of Hawick), a sister, a cousin, a niece, a girlhood friend and not just a mother. Born Ellen Irvine at Allars Crescent when it was a bowed row of tenements behind the west end of the High Street, she had seen Cornets raise the banner high only yards away from where she had grown up. The summer colour of the rideouts, the songs, the chase, the Mair and the shows at the Haugh were bright threads woven into her earliest days. One of seven sisters and a solitary brother, my mum was raised in a tiny flat, in the body warmth of a crowded, noisy and vivid family. Seventy years later, when my dad died, her bewilderment was more than emotional. She told me it would be the first time in her life she had not shared a bed.

At the Common Ridings, I inherited a powerful sense of the closeness of the Irvines. My aunties Mary, Jean, Daisy, Isa and Margaret and my uncle David all gathered at the Mair, always spreading out rugs and a vast picnic at what seemed to be exactly the same place. Even the ghost of Auntie Mina, who died before we could know her, seemed to linger there. In the June sunshine, we celebrated. With all my Hawick cousins, there must have been thirty or forty eating sandwiches, drinking lemonade or something stronger, watching the races, the purples, yellows, reds, blues and greens of the jockeys silks shining in the sun, the rumble of hoof beats, the cheering crowds, my aunties shaking their heads at one or two neighbours who had celebrated too well and appeared to have lost control of their legs.

In those distant summers of the 1950s and early 1960s, Hawick seemed to me a wonderland of generous laughter and music. Exotic too the shows at the Haugh smelled of spun candyfloss, hot dogs and onions, and in the air was the faint, electric whiff of disrepute. I loved it. My uncles often gave me a half-crown so that I could go on the dodgems or the Waltzer or shoot tiny, feathered darts out of ancient rifles with bent barrels. As the men jingled change in the pockets of their flannels their tweed sports jackets, Van Heusen shirts and club ties immaculate and the women wore new dresses, it occurred to me that Hawick people had come to their own party. There was a sense of a long celebration punctuated by mysterious rituals everyone understood, gatherings at specific places at specific times and a simple pride. Hawick was all dressed up to celebrate no more and no less than itself.

There was also a palpable sense of escape. From the deafening rattle and clack of the mills where most of my aunties worked, they were released into the June sunshine for the Common Riding. The mills fell silent then but, for the rest of the year, they meant money and, more significantly, money for women, who were in a large majority on the dozens of weaving and knitting flats. Nimble fingers, a keen eye and an uncomplaining attitude to the endless repetition of textile production had delivered jobs in abundance for women. When I began to go to Hawick Common Riding with my mum in the mid 1950s and into the 1960s, there was money in Hawick and most of it in purses and handbags rather than wallets and back pockets.