THE

HIDDEN

WAYS

Also by Alistair Moffat

Scotland, A History from Earliest Times

Bannockburn: The Battle for a Nation

The British: A Genetic Journey

The Reivers

The Wall: Romes Greatest Frontier

Before Scotland

The Sea Kingdoms

The Borders: A History

Tyneside: A History of Newcastle and Gateshead from

Earliest Times

Tuscany: A History

THE

HIDDEN

WAYS

ALISTAIR MOFFAT

Published in Great Britain in 2017 by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

canongate.co.uk

This digital edition first published in 2017 by Canongate Books

Copyright Alistair Moffat, 2017

The moral right of the author has been asserted

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 78689 101 3

eISBN 978 1 78689 102 0

Typeset in Dante MT by Palimpsest Book Production Ltd, Falkirk, Stirlingshire

In memory of my father, John Lauder Moffat

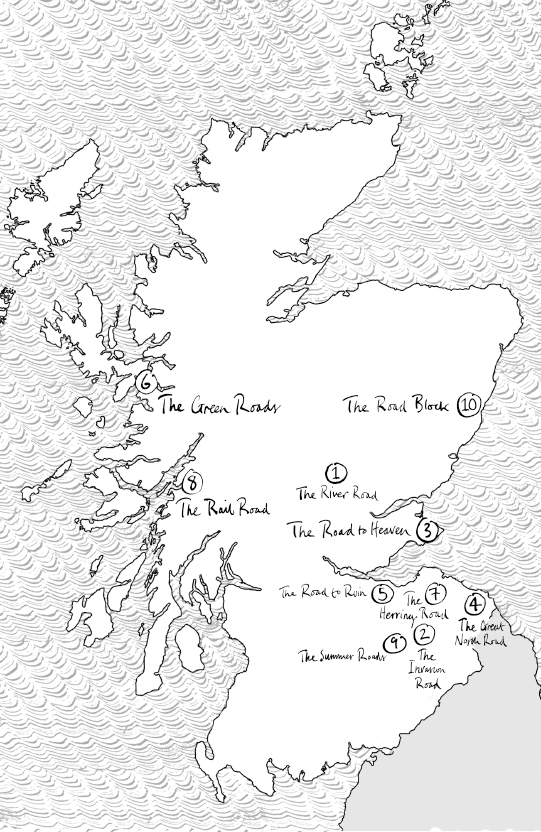

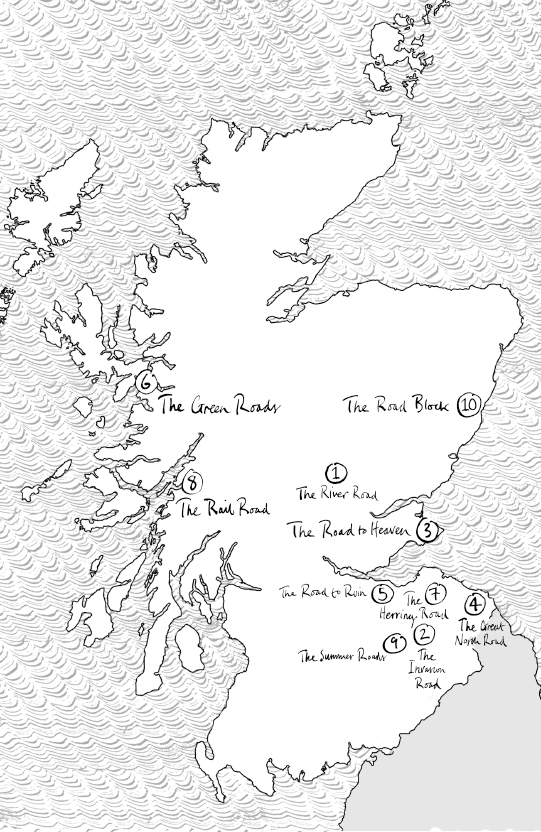

Contents

The First Steps

When I am going that way, I often pull in by the side of a single-track road that passes the farm where my grandmother was born. Cliftonhill sits on the south-facing slopes of the valley of the Eden Water, near Kelso in the Scottish border country. And it is beautiful. Near the field entry where I stop, there is a gap in the hedge that lets me look down to the Eden Water winding its lazy way to join the Tweed a mile or two to the east. The contours of the fields are old, and they are moulded to the meander of the little river. On the opposite bank, they climb up to Hendersyde Farm.

Nothing much has changed since 1896, the year my grannie was born. What I see when I lean on the fence a few metres from her farm cottage is what she saw as a child, and it moves me very much. I seem to slip through a crack in time, back to when Bina was a four year old looking for hens eggs around the stackyard, helping to lead the milker cows into the evening byre, waving a stick and shouting at the bullocks to help her mother and grandfather move them onto new grazing. These were the everyday stories she told me, what Bina called the auld life on the land. To walk to where she once stood and look south over the folded ridges leading up to the dark heads of the Cheviots is to let me walk beside her once more.

Bina lived in a crowded, two-room cottage, full of women and one man, her grandfather, William Moffat. He was First Horseman at Cliftonhill, the old term for the head ploughman. With his wife, Margaret Jaffrey (in Scotland, women often kept their maiden name and it is what is inscribed on her tombstone in the kirkyard at Ednam, the village at the foot of the hill), William had four daughters. My great-grandmother, Annie Moffat, also kept her name but only because she had no husband. Baby Bina was illegitimate.

Early one summer morning I decided to walk where Annie and my old great-aunts walked. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries many women worked in the fields and because of the nature of their contracts with farmers and the men they hired, they were called bondagers. Wearing bonnets with a wide brim around their faces to keep out the rain and the sun, and full skirts to do the same, these women would rise early, pull on their hob-nail boots, shoulder their hoes and walk down the hill to the bottom fields by the Eden to swing open the gate to the turnip field. When I walked where they walked, I fancied I could hear the clatter of their boots and their quiet chatter as the mist lifted off the little river. For a moment I was with them, these people who made me, and through the damp earth and the fresh smell of green I intuited something of the rhythm of their lives.

That walk has stayed with me. It prompted me to begin thinking about this book and the project that goes with it, about how vital it was to stop, get out of the car (or off the train or bus) and not to see the countryside through the glass of a windscreen or a window. Anyone who wants to understand something of the elemental nature of our history should try to walk through it, should listen for the natural sounds our ancestors heard, smell the hedgerow honeysuckle and the pungent, grassy, milky stink of cowshit, look up and know something of shifts in the weather and the transit of the seasons and feel the earth that once was grained into their hands.

This is not a set of romantic, ahistorical notions, or a rash of New Age nonsense, but a necessity for anyone who seriously wishes to understand the texture, the feel of the millions of lives lived on the land of Scotland, lives that are rarely recorded anywhere. To walk in the footsteps of our ancestors is to sense some of that everyday experience come alive under our feet. The cities and large towns where most Scots now live are very recent and the habit of working indoors in well-heated and lit factories or offices, usually sitting down, is also very new, little more than two centuries old. Even as late as 1900, more than 400,000 Scots worked on farms, far more than in heavy industry, or mining or the building trades. And they were out in all weathers, often cold, sometimes wet through, old sacking across their shoulders long since sodden. Before the industrial and agricultural revolutions of a century or more before, almost all Scots worked and lived on the land or had a close link with food production of some kind. For the overwhelming balance of our history, the 11,000 years since the end of the last Ice Age, the Scots have been country people.

And except for the tiny minority who owned horses, we walked everywhere. That habit died much more recently, within the span of my own lifetime. When the age of mass transport arrived in the late nineteenth century, ordinary people sometimes travelled on trains, if they could afford it. But it was not until the early 1960s when car ownership became possible for most (even if it was an old banger) that we stopped walking. My mother, Ellen Irvine, worked in the Hawick mills in the 1930s, and she and her sisters would think nothing of walking seven or eight miles or more to a country dance in a village hall, and then walking seven or eight miles home afterwards. There was no alternative.

Now, we sit and stare blankly out of a car windscreen or train window, and we see the countryside rush past as little more than the space between destinations. We are missing a great deal. Certainly, important moments in Scotlands history happened in (very small) towns such as Edinburgh, St Andrews and Stirling. But in Walter Scotts excellent phrase, that tended to be the big bow-wow stuff. Almost all of us come from generations of ordinary people who worked the land, and to understand something of their lives we should find a pair of boots and a map, and try to walk where they walked.

The Hidden Ways began as a highly personal journey back into the twilight of the past, but I quickly realised that what I was doing might have a wider application, be a good way of connecting with the experience of a hundred generations of Scots, going back 2,000 or 3,000 years, far back into the darkness of the deep past, beyond the reach of genealogy or written records of any kind. Many modern roads overlie much older ways, tracks where people walked from where they lived to towns or villages, or between them. It occurred to me that if the faded map of roads no longer travelled in Scotland could be made vivid once more, then that would allow many people to walk beside the ghosts of an immense past, beside their people.