Above: Late Iron Age bronze figurine of a female dancer, from Neuvy-en-Sullias, France.

Frontispiece:

Late Iron Age bronze boar, from Neuvy-en-Sullias, France.

About the Author

Miranda Aldhouse-Green is Professor Emeritus at Cardiff University. She specializes in the study of shamanism and archaeology of the Iron Age. She has published widely on the Celts and their world, including: Celtic Goddesses: Warriors, Virgins and Mothers, Dictionary of Celtic Myth and Legend, and Exploring the World of the Druids.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

The Egyptian Myths

The Greek and Roman Myths

Exploring the World of the Druids

Exploring the World of the Celts

The Historical Atlas of the Celtic World

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

For Stephen

amoris causa

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to many people who helped make this book happen. To family and friends who patiently endured my obsessive ramblings about myths, a huge thank you. I owe the greatest debt of gratitude to the staff of Thames & Hudson, particularly Colin and Alice. My three Burmese cats Dido, Persephone and Taliesin kept me company during the long solitary hours of writing. The dedication of this book to Stephen is intended to tell him how much I appreciate him and his unending support.

CONTENTS

Prelude

The Celtic World: Space, Time and Evidence

Finale

Paganism and Christianity: The Transformation of Myth

Then Conchubar, the subtlest of all men,

Ranking his Druids round him ten by ten,

Spake thus: Cuchulain will dwell there and brood

For three days more in dreadful quietude,

And then arise, and raving slay us all,

Chaunt in his ear delusions magical,

That he may fight the horses of the sea.

The Druids took them to their mystery,

And chaunted for three days.

FROM CUCHULAINS FIGHT WITH THE SEA, W. B. YEATS

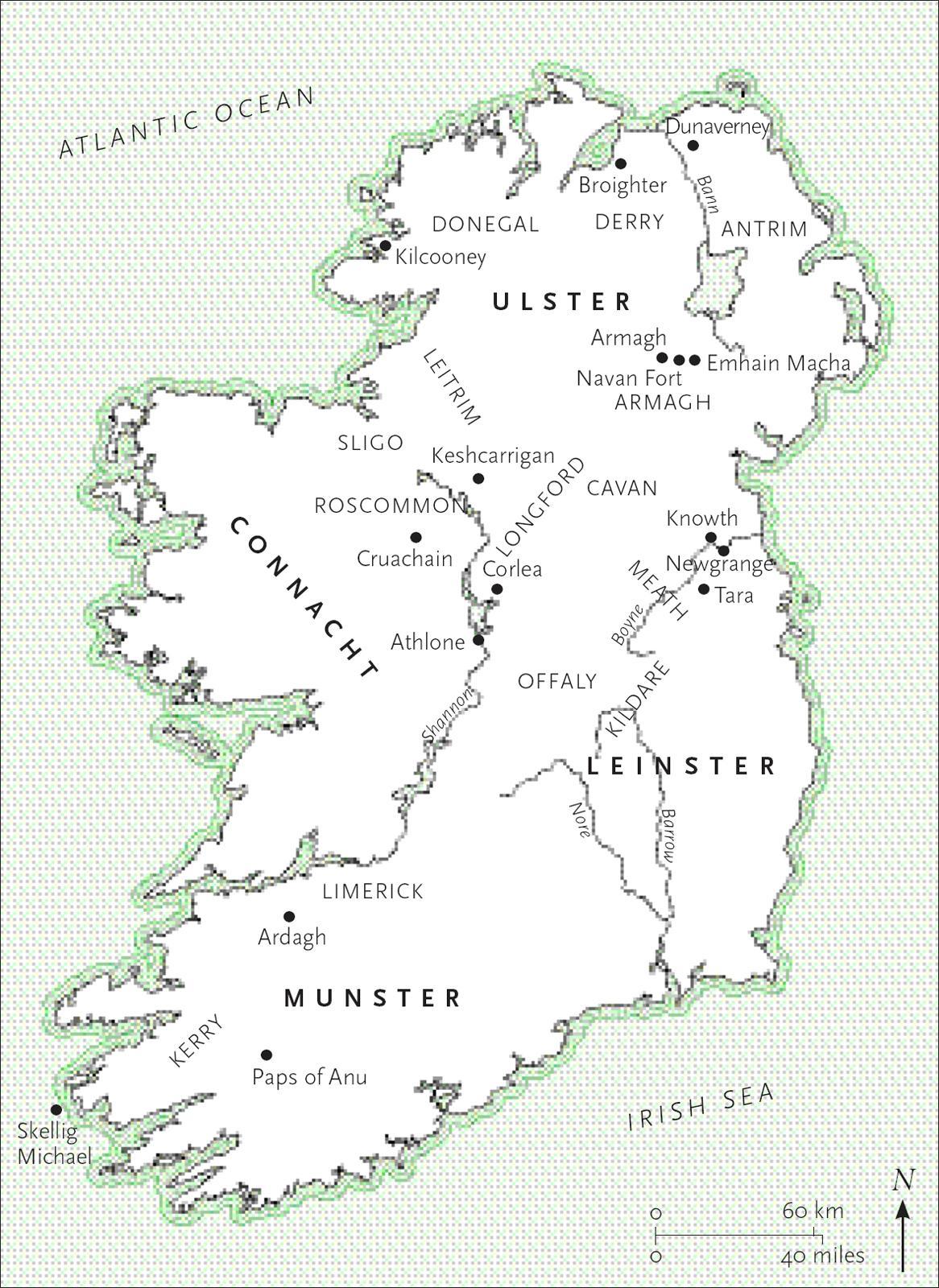

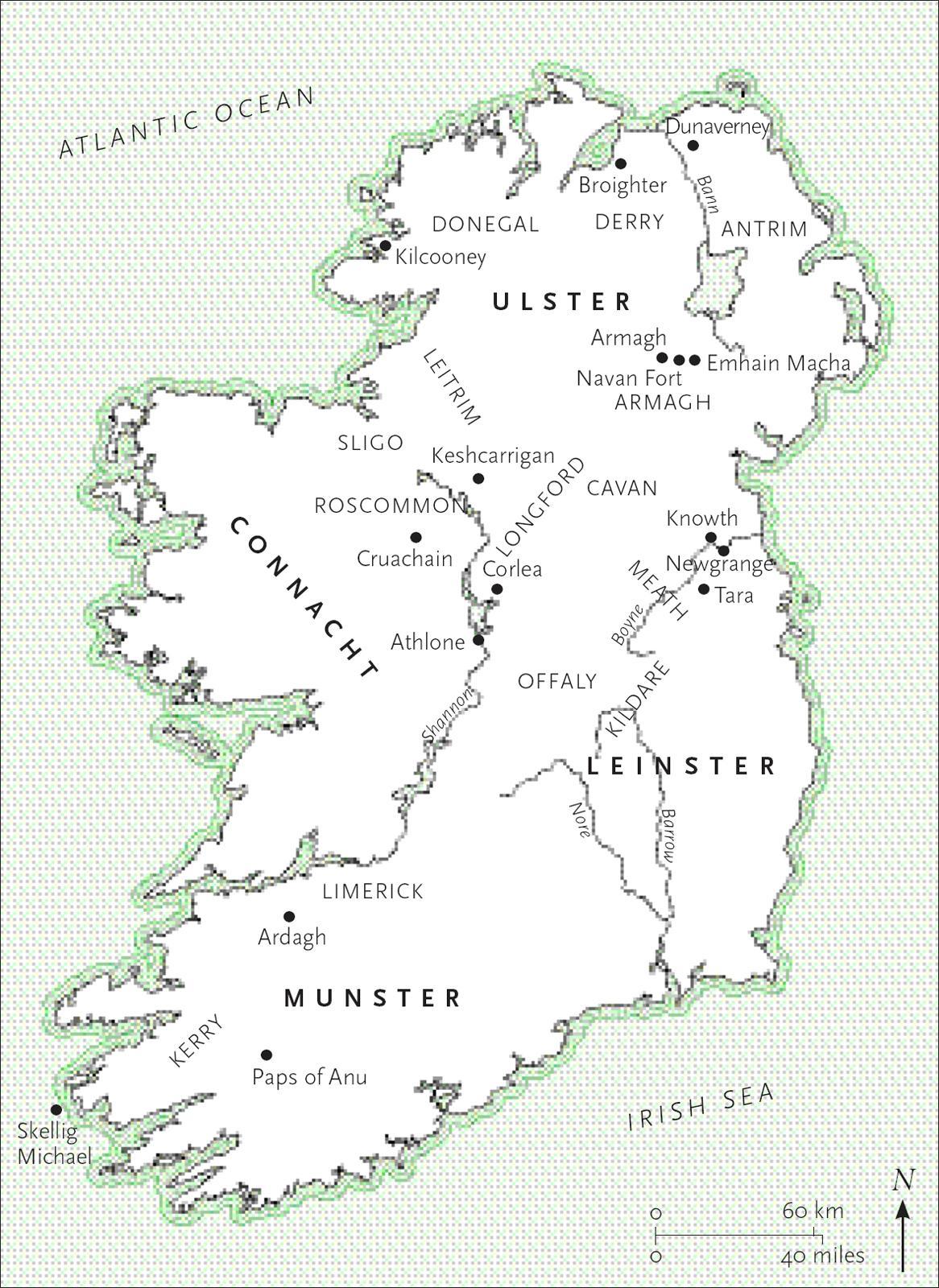

Map of Ireland with regions and sites mentioned in the text

Martin Lubikowski, ML Design, London

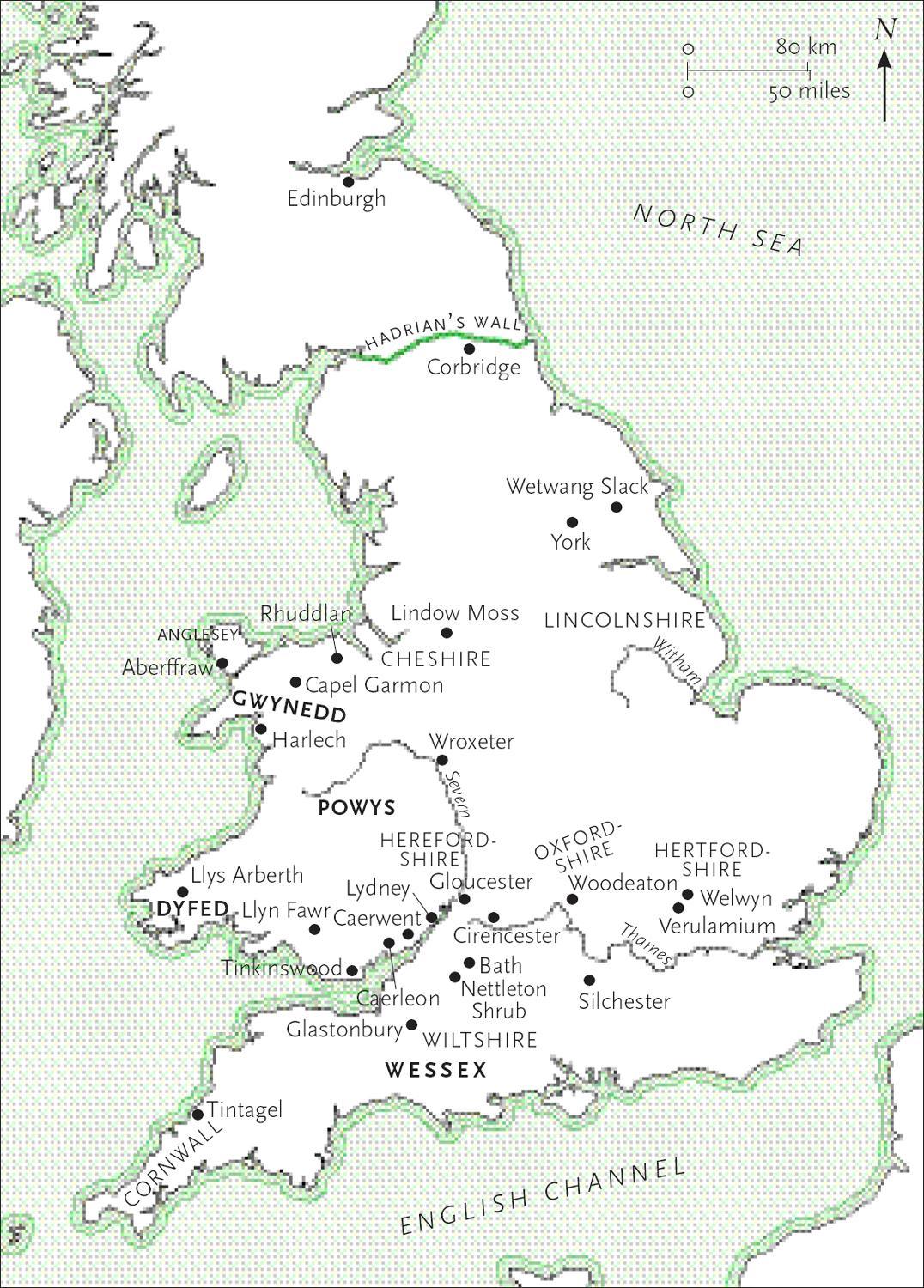

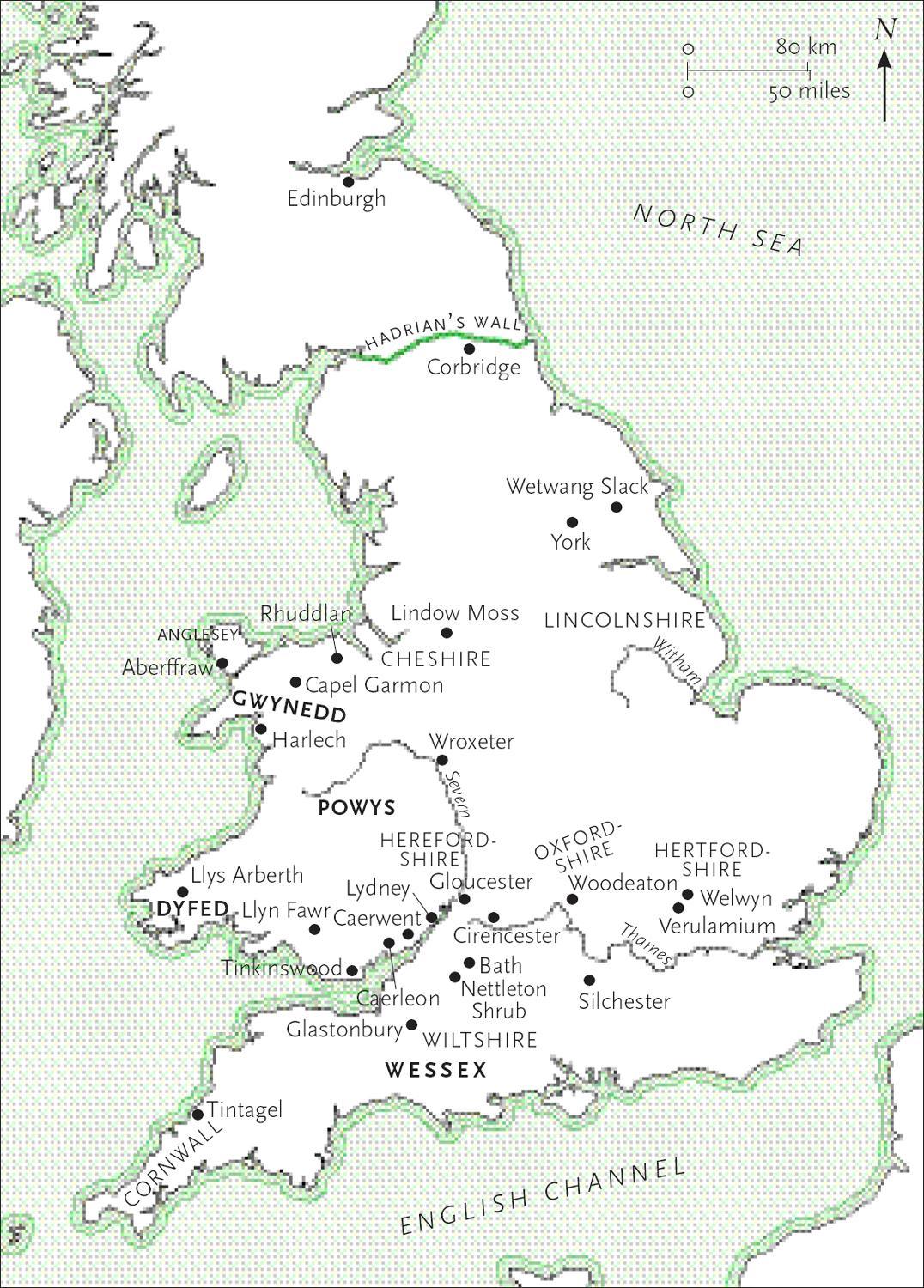

Map of England and Wales with regions and sites mentioned in the text

Martin Lubikowski, ML Design, London

Gaul as a whole consists of three separate parts: one is inhabited by the Belgae, another by the Aquitani and the third by the people we call Gauls, though in their own language they are called Celts.

CAESAR, DE BELLO GALLICO 1.1

The principal focus of this book is the myths found in the early medieval literature of Ireland and Wales that dates, in its written form, to between the 8th and 14th centuries AD. It was with considerable trepidation that I embarked upon a book with the term Celtic in the title. Since the early 1990s, archaeologists have seriously questioned the use of the word to describe the ancient Iron Age peoples of Western and Central Europe. Particular opprobrium has been attached to the use of Celts when referring to ancient Britain. Whilst a plethora of authors from the Classical world allude to the people of Gaul (roughly speaking France, Switzerland, Germany west of the Rhine, parts of northern and eastern Iberia and the far north of Italy) as being Celtic, no ancient author ever spoke so of Britain. The Romans called the British Britanni.

A major issue that the anti-Celtic lobby has with the term, in reference to ancient Europeans, is that it blurs the differences that clearly existed between peoples with widely divergent cultures and worldviews. It also means that some regions, such as the far north of Europe, are excluded from the Celtic umbrella, even though many cultural similarities between these areas and those further south can be identified in archaeological evidence. Julius Caesar knew Gaul intimately because he and his army were stationed there for nearly ten years. The opening of his De Bello Gallico (Concerning the Gallic War) spoke of the now-famous division of the country into three major cultural groups: the Aquitani of the west, the Belgae in the east and the Celts who occupied the centre of Gaul. Caesar specifically stated that this last group identified themselves as Celts. This is important. For the most part, it is impossible to prove self-determination for prehistoric communities because they were non-literate and therefore written evidence of their own is absent. Even Caesars use of the name Celts may have been nothing more than his presentation of a neat division that actually masked huge divergences within this group.

Despite the problems of knitting together ancient and early medieval identities, one important thing binds them together: language. Where there is evidence, for example from early and rare inscriptions or from place names recorded in Graeco-Roman geographies, it appears that the Celtic languages known and spoken today had their roots firmly in antiquity, for they are traceable in Gaulish, Celtiberian and old British words. It is true that language does not equate with ethnicity, but it does contribute powerful connective tissue. It is widely recognized, for example, that the use of the English tongue outside the United Kingdom carries with it a certain amount of cultural baggage, in spite of the yawning cultural gulfs between anglophone countries.

Names are essentially labels. Ancient Greece encompassed a series of city states Athens, Sparta, Corinth and many more united by a common language but regarding themselves as completely distinct. The Roman empire embraced a great swathe of the ancient world: from Britain to Arabia, people thought of themselves as belonging both to their indigenous communities and also to Rome. So, in the Biblical Acts of the Apostles, Paul of Tarsus confidently asserted that he was a civis romanus, a citizen of Rome, while at the same time he was a member of the wildly independent state of Judaea. So the question one can raise is this: is the use of the term Celtic any less legitimate as a label to describe peoples with certain important shared cultural elements than the term Greek or Roman? I think not.

Another issue to be considered is the origin of the term Celtic as being used to describe the languages and peoples that we now take for granted as Celts: the Irish, Welsh, Scottish, Cornish, Manx, Bretons and Galcians. It was the 16th-century Classical scholar George Buchanan who first developed the notion of the Celts as a unified group of peoples living in Ireland and mainland Britain. So the concept of Celticity, as applied to Wales, Ireland and other regions on the western edge of Europe, is comparatively modern (in contrast with Caesars use of the term in antiquity for those Celts he encountered on the Continent). Nonetheless, self-identity as a Celt is hugely important to the inhabitants of modern Celtic nations, such as Ireland and Wales. If people think of themselves as possessing a certain identity, that in itself gives credibility to that self-determination. For how else were identities created in the first place?

Next page