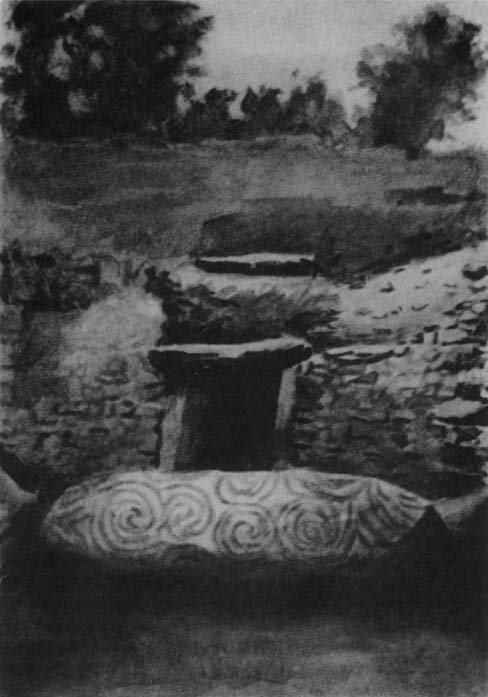

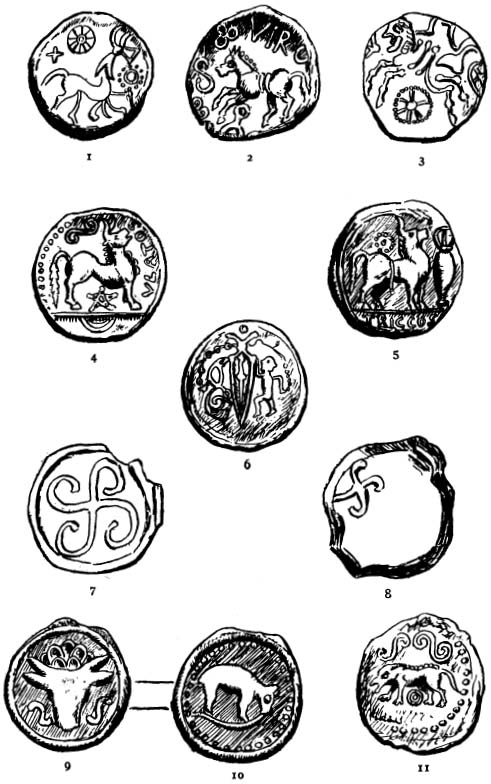

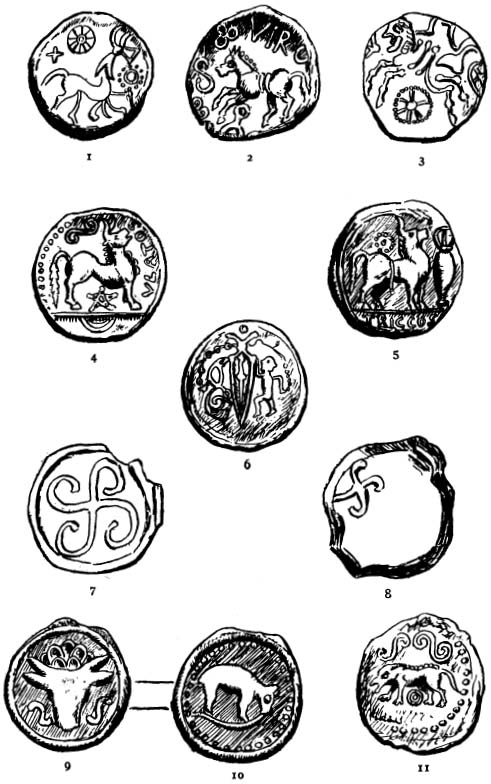

PLATE I

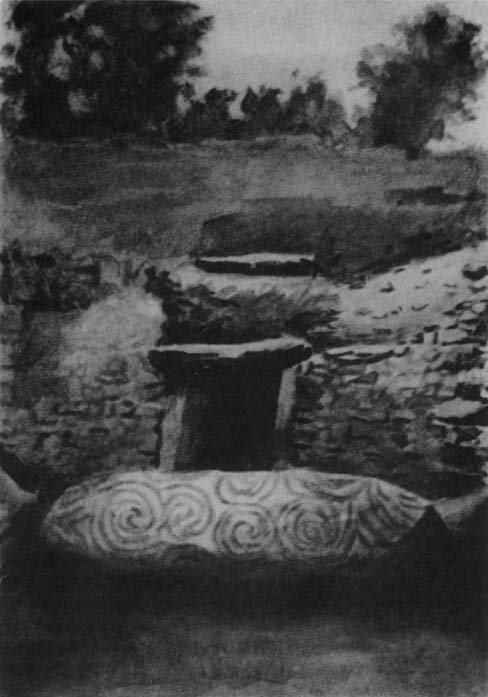

B RUG NA B OINNE

The tumulus at New Grange is the largest of a group of three at Dowth, New Grange, and Knowth, County Meath, on the banks of the Boyne in the plain known to Irish tales as Brug na Boinne, the traditional burial-place of the Tuatha D Danann and of the Kings of Tara. It was also associated with the Tuatha D Danann as their immortal dwelling-place, e. g. of Oengus of the Brug (see pp. 5051, 6667, 17677). The tumuli are perhaps of the neolithic age (for plans see Plate VI, A and B).

Published in 1996 by

Academy Chicago Publishers

363 West Erie Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

1918 J. A. MacCulloch

ISBN 0-89733-433-7

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

PLATE

1. Horse and Wheel-Symbol

2. Horse, Conjoined Circles and S-Symbol

3. Man-Headed Horse and Wheel

4. Bull and S-Symbol

5. Bull

6. Sword and Warrior Dancing Before it

78. Swastika Composed of Two S-Symbols (?)

910. Bulls Head and two S-Symbols; Bear Eating a Serpent

11. Wolf and S-Symbols

1. Animals Opposed, and Boar and Wolf (?)

2. Man-Headed Horse and Bird, and Bull Ensign

3. Squatting Divinity, and Boar and S-Symbol or Snake

4. Horse and Bird

5. Bull and Bird

6. Boar

7. Animals Opposed

1. The Picardy Stone

2. The Newton Stone

1. The Crichie Stone

2. An Incised Scottish Stone

1, 6. Carvings of Bulls from Burghhead

25. S-Symbols

TO

DR. JAMES HASTINGS

E DITOR OF THE Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics,

THE Dictionary of the Bible, ETC .

WITH THE GRATITUDE AND RESPECT OF THE AUTHOR

AUTHORS PREFACE

I N a former work I have considered at some length the religion of the ancient Celts; the present study describes those Celtic myths which remain to us as a precious legacy from the past, and is supplementary to the earlier book. These myths, as I show, seldom exist as the pagan Celts knew them, for they have been altered in various ways, since romance, pseudo-history, and the influences of Christianity have all affected many of them. Still they are full of interest, and it is not difficult to perceive traces of old ideas and mythical conceptions beneath the surface. Transformation allied to rebirth was asserted of various Celtic divinities, and if the myths have been transformed, enough of their old selves remained for identification after romantic writers and pseudo-historians gave them a new existence. Some mythic incidents doubtless survive much as they were in the days of old, but all alike witness to the many-sided character of the life and thought of their Celtic progenitors and transmitters. Romance and love, war and slaughter, noble deeds as well as foul, wordy boastfulness but also delightful poetic utterance, glamour and sordid reality, beauty if also squalid conditions of life, are found side by side in these stories of ancient Ireland and Wales.

The illustrations are the work of my daughter, Sheila MacCulloch, and I have to thank the authorities of the British Museum for permission to copy illustrations from their publications; Mr. George Coffey for permission to copy drawings and photographs of the Tumuli at New Grange from his book New Grange (Brugh na Boinne) and other Inscribed Tumuli in Ireland; the Librarians of Trinity College, Dublin, and the Bodleian Library, Oxford, for permission to photograph pages from well-known Irish MSS.; and Mr. R. J. Best for the use of his photographs of MSS.

In writing this book it has been some relief to try to lose oneself in it and to forget, in turning over the pages of the past, the dark cloud which hangs over our modern life in these sad days of the great war, sad yet noble, because of the freely offered sacrifice of life and all that life holds dear by so many of my countrymen and our heroic allies in defence of liberty.

J. A. MACCULLOCH.

B RIDGE OF A LLAN, S COTLAND,

May, 16, 1916.

The Religion of the Ancient Celts, Edinburgh, 1911.

INTRODUCTION

I N all lands whither the Celts came as conquerors there was an existing population with whom they must eventually have made alliances. They imposed their language upon them the Celtic regions are or were recently regions of Celtic speech but just as many words of the aboriginal vernacular must have been taken over by the conquerors, or their own tongue modified by Celtic, so must it have been with their mythology. Celtic and pre-Celtic folk alike had many myths, and these were bound to intermingle, with the result that such Celtic legends as we possess must contain remnants of the aboriginal mythology, though it, like the descendants of the aborigines, has become Celtic. It would be difficult, in the existing condition of the old mythology, to say this is of Celtic, that of non-Celtic origin, for that mythology is now but fragmentary. The gods of the Celts were many, but of large cantles of the Celtic race the Celts of Gaul and of other parts of the continent of Europe scarcely any myths have survived. A few sentences of Classical writers or images of divinities or scenes depicted on monuments point to what was once a rich mythology. These monuments, as well as inscriptions with names of deities, are numerous there as well as in parts of Roman Britain, and belong to the Romano-Celtic period. In Ireland, Wales, and north-western Scotland they do not exist, though in Ireland and Wales there is a copious literature based on mythology. Indeed, we may express the condition of affairs in a formula: Of the gods of the Continental Celts many monuments and no myths; of those of the Insular Celts many myths but no monuments.

The myths of the Continental Celts were probably never they were tabu, and doubtless their value would have vanished if they had been set forth in script. The influences of Roman civilization and religion were fatal to the oral mythology taught by Druids, who were ruthlessly extirpated, while the old religion was assimilated to that of Rome. The gods were equated with Roman gods, who tended to take their place; the people became Romanized and forgot their old beliefs. Doubtless traditions survived among the folk, and may still exist as folk-lore or fairy superstition, just as folk-customs, the meaning of which may be uncertain to those who practise them, are descended from the rituals of a vanished paganism; but such existing traditions could be used only with great caution as indexes of the older myths.

There were hundreds of Gaulish and Romano-British gods, as an examination of the Latin inscriptions found in Gaul and Britain

PLATE II

G AULISH C OINS

1. Coin of the Nervii, with horse and wheel-symbol (cf. Plates III, 4, IV, XV).

2. Gaulish coin, with horse, conjoined circles, and S-symbol (cf. Plates III, 3, IV, XIX, 25).

3. Coin of the Cenomani, with man-headed horse (cf. Plate III, 2) and wheel.

4. Coin of the Remi (?), with bull (cf. Plates III, 5, IX, B, XIX, 1, 6, XX, B, XXI), and S-symbol.

5. Coin of the Turones, with bull.

6. Armorican coin, showing sword and warrior dancing before it (exemplifying the cult of weapons; cf. ).

7. 8. Gaulish coins, with swastika composed of two S-symbols (?).

9, 10. Gaulish coin, showing bulls head and two S-symbols; reverse, bear (cf. Plate XXIII) eating a serpent.

Next page