Page List

Published in 2008 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2008 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

First Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

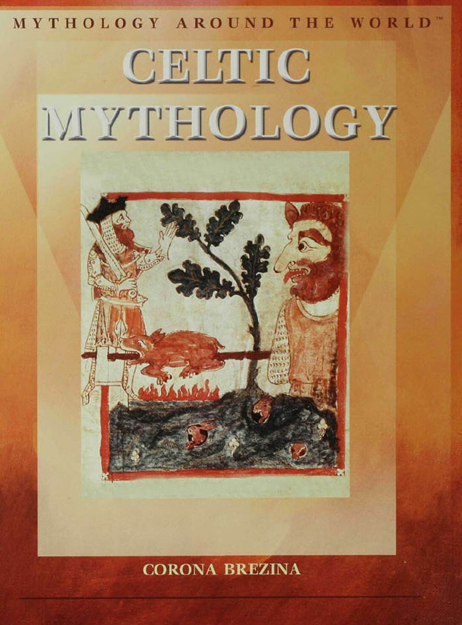

Brezina, Corona.

Celtic mythology / Corona Brezina.1st ed.

p. cm.(Mythology around the world)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4042-0737-0

ISBN-10: 1-4042-0737-6

1. Mythology, Celtic.

I. Title. II. Series.

BL900.B74 2006

299.16113dc22

2005035262

Manufactured in the United States of America

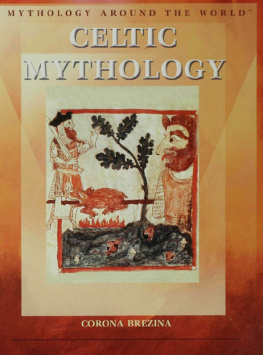

On the cover: King Arthur confronts a giant who is roasting a boar in this fourteenth-century manuscript illumination.

CONTENTS

T he Celts were an ancient people whose culture once spread across much of Europe. According to several accounts written by Roman historians, they were fierce fighters who struck terror into their enemies. Due to this strong warrior tradition, Celtic mythology is dominated by tales of courageous combatants, their great feats, and activities related to tribal life, such as hunting and feasting.

This third-century-BC gold brooch from Spain depicts a helmeted, naked Celtic warrior leaning on his shield as his dog leaps toward him.

Bardstribal poets and singerswere said to have learned thousands of verses by heart, most of them dealing with heroic deeds. With the unlikely help of the Christian monks who supplanted the pagan bards, invaluable pieces of this rich, luminous oral tradition were recorded and preserved for the enjoyment and illumination of future generations. Though many of the legends have no doubt been lost to time, a wealth of material remains, and it provides a fascinating glimpse into the magical and mysterious world of the Celts.

T he Celts emerged as a distinct culture during the early first millennium BC. They quickly expanded beyond their original homelands in central Europe, spreading west toward Spain, east to Turkey, and south toward the Italian peninsula. By the fourth century BC, the Greeks considered the Celts one of the major barbarian nations of the known world. The Celts migrated to Britain by the fifth century BC (although there may have been even earlier Celtic settlements there) and established a presence in Ireland by the third century BC.

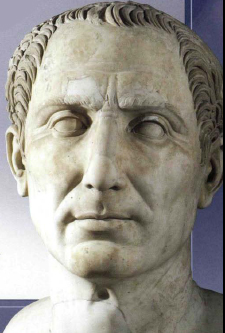

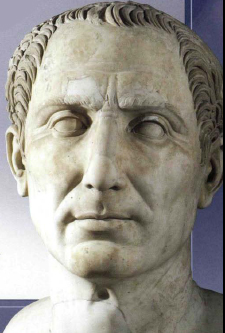

The Roman emperor Julius Caesar is depicted in this marble bust.

The Celtic realm was not a centrally organized empire. The Celtic people were composed of numerous independent, self-governing tribes bound together by a common culture. They shared a common religion (a pagan, nature-based worship), dress, social and political institutions, and related languages. Two branches of the Celtic language were spoken in the British IslesGoidelic (or Gaelic) and Brythonic (or Brittonic). The main difference between the two is that Brythonic words that begin with B or P begin with C or K in the Goidelic languages. The three surviving Goidelic languages are Irish (Gaeilge), Scottish Gaelic (Gidhlig), and Manx (Gaelg; spoken on the Isle of Man). The surviving Brythonic languages are Welsh (spoken in Wales), Breton (spoken in Brittany, a Celtic region of France), and Cornish (spoken in the Cornwall area of England).

The Romans referred to the Celts of continental Europe as the Gauls. In 390 BC, Celtic tribes invaded Italy and captured Rome. Following the sack of Rome, by the beginning of the third century BC, the Celts were at the height of their power. But they were soon themselves beset by Germanic and Dacian tribes (the Dacians were from present-day Romania) to the north and east and the growing Roman Empire to the south. As a result, the Celtic domain gradually began to disintegrate and disappear from continental Europe.

The Roman emperor Julius Caesar led a series of military campaigns against Gaul, most of which is in present-day France. In 58 BC, Gaul fell to Caesar and was incorporated into the Roman Empire. A century later, the Romans conquered Celtic Britain. When Roman rule ended five hundred years later, Roman soldiers were quickly replaced by Germanic Anglo-Saxon invaders. Only a few British regions, including Wales, parts of Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Cornwall, retained their Celtic traditions.

Neither the Roman nor the Anglo-Saxon invaders ever extended their rule into Ireland. Celtic Ireland remained free of outside influences until the arrival of Christian missionaries in the fifth century AD, and later, Viking explorers and raiders. Celtic culture survivedand even flourishedin Ireland long after the rest of the Celtic realm had crumbled throughout the rest of Europe and the British Isles. Because of this, early Irish texts are a particularly valuable source of information on Celtic lore.

The Keepers of Celtic Tradition

Each Celtic tribe was headed by a king, who presided over a warrior class of nobles as well as a class of farmers and free men. A separate class of mendruids, bards, and seersoversaw the cultivation and preservation of literature, education, and religious practices.

The druids were the priestly order of the Celts. They were highly respected and feared because of their connection to the supernatural realm. They oversaw sacrifices (possibly including human sacrifices) and the worship of the gods and mediated between the human and the spirit world. The druids emphasized that the soul did not cease to exist with death but simply passed into another body. The resulting indifference to death may account for the legendary bravery of Celtic warriors. The Celts were so unconcerned with the possibility of death that they were known to go into battle naked and sometimes unarmed.

A Celtic warrior is seen fleeing in this second-century-BC sculpture found in Italy. Roman artists frequently depicted Dying Gauls, Celtic soldiers dying nobly on the battlefield after being vanquished by their Roman enemies.

Druidic knowledge was an oral tradition. Although some druids could read and write using the Greek alphabet, they did not consider it proper to preserve written records of druidic teachings. Instead, they memorized and passed down to each succeeding generation of druids vast amounts of poetry, history, religious matter, genealogies (family trees), law, science, healing, and other knowledge. It took twenty years of training for a student to master all of this druid lore.

The areas of expertise among the druids, bards, and seers frequently overlapped. Bards performed music and recited long epic poems (which were often sung). They were thought to possess magic in their voices and have the gift of prophecy. The Celts believed that the spoken word held great power. Like the druids, bards were held in high esteem among the Celts. A patron once gave the legendary Welsh bard Taliesin a hundred racehorses, a hundred bracelets, and many other valuable gifts.