Published in 2018 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2018 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

First Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Brezina, Corona, author.

Title: Galileo Galilei / Corona Brezina.

Description: First edition. | New York: Rosen Publishing, 2018. |

Series: Leaders of the scientific revolution | Audience: Grades 7 to 12. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016053794 | ISBN 9781508174684 (library bound)

Subjects: LCSH: Galilei, Galileo, 15641642Juvenile literature. | AstronomersItalyBiographyJuvenile literature. | Physicists ItalyBiographyJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC QB36.G2 B638 2018 | DDC 520.92 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016053794

Manufactured in the United States of America.

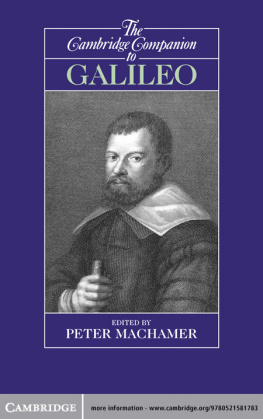

On the cover: This portrait of Italian mathematician, scientist, and astronomer Galileo Galilei (15641642) was painted in the seventeenth century. Background: This page from Galileos 1613 book Istoria e dimostrazioni intorno alle macchie solari e loro accidenti (History and demonstrations concerning sunspots and their properties) shows the changes in sunspots that he observed.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER ONE

GALILEOS EARLY LIFE

CHAPTER TWO

MATHEMATICS, MECHANICS, AND MOTION

CHAPTER THREE

PEERING THROUGH THE TELESCOPE

CHAPTER FOUR

COPERNICANISM AND CONTROVERSY

CHAPTER FIVE

THE DIALOGUE AND CONDEMNATION

CHAPTER SIX

TWO NEW SCIENCES AND GALILEOS LEGACY

TIMELINE

GLOSSARY

FOR MORE INFORMATION

FOR FURTHER READING

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

O n June 22, 1633, a frail sixty-nine-year-old man was led to the great hall at the church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva in Rome, Italy. Dressed in penitential white clothing, he had been released from confinement earlier in the morning. A crowd of Catholic clergy was assembled to watch the proceedings. The accused knelt before his judges to hear their findings on the charge of heresydoctrines contradicting church teachings.

The old man was the acclaimed astronomer Galileo Galilei. He was awaiting the ruling on his trial for the crime of teaching Copernicanism, the theory that the earth revolves around the sun. According to the contemporary Catholic Church, the earth was the stationary center of the universe around which all heavenly bodies orbited. Official condemnation was about to silence Galileo on the troublesome topic forever.

An 1847 painting depicts the condemnation of Galileo Galilei in 1632 by the Catholic Church. The trial and sentencing served to silence Galileos defense of the theories of Copernicus.

At last, the judgment and sentence were announced. Galileo was found vehemently suspected of heresya clear verdict of guilty. He was sentenced to indefinite imprisonment, and his book advocating Copernicanism was banned. But the humiliation was not complete. He was required to abjure, or publicly renounce, his controversial views. He read out a statement acknowledging that he had erred, and swore on the Bible that he would never again repeat his heresy.

A story exists claiming that after finishing the statement, he muttered as an aside, And yet, it moves. Historians agree that this incident is a myth. Even so, some of Galileos most important scientific work served to prove that the earth does indeed move.

Galileo had stunned the world with the astronomical discoveries he made using his new instrument, the telescope. He showed that moons orbited Jupiter. The moon had mountains and valleys. Sunspots periodically flared on the surface of the sun.

Galileos astronomical achievements brought him fame, and few people gazing through the telescope could deny the evidence before their own eyes. Nevertheless, his observations led him to conclusions that conflicted with the conventionally accepted model of the universe. When he persisted in publicizing his theories about the earth orbiting the sun, the Catholic Church moved to condemn him.

Today, Galileo is considered one of the key figures of the Scientific Revolution. In addition to his astronomical breakthroughs, Galileo improved the design of the telescope, invented many other mechanical devices and instruments, and made new discoveries in physics. His work helped science make the transition from the medieval age to the modern.

CHAPTER ONE

GALILEOS

EARLY LIFE

G alileo Galilei was born in Pisa, Italy, on February 15, 1564. His father, Vincenzo Galilei, was a highly regarded musician from Florence, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, who played the lute. His mother, Giulia Ammananti, came from a respectable family of cloth merchants. After their marriage in 1562, they settled down in her hometown of Pisa. In accordance with a Tuscan custom, their eldest son was given the first name Galileo that was a variant form of the family name, Galilei. Later in life, after he became famous, Galileo would refer to himself by his first name only, as is the common practice today.

Vincenzo Galilei was a performer and teacher, but today, he is best remembered for his study of music theory. He advocated revolutionary ideas about harmony and tuning that challenged musical conventions of the day. Vincenzo even conducted experiments that tested the properties of lute strings, such as how the tension of different materials affected musical pitch. Galileo probably helped his father in this experimentation.

Pisa, seen here in a sixteenth-century print, was ruled from afar by Cosimo de Medici, grand duke of Florence. Cosimo rejuvenated the town through public works projects and support of learning and the arts.

THE MEDICIS OF FLORENCE

Florence in Galileos time was the capital of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, an independent state located in west-central Italy and ruled by a branch of the powerful Medici family. The Medicis attained their vast wealth through banking and trade. The first grand duke was Cosimo I de Medici, who took the title in 1569. The Medicis were renowned supporters of the artsVincenzo Galilei largely made his living at the grand dukes court. Galileo himself would be supported by Cosimos eventual successors, Cosimo II and Ferdinando II. But Ferdinando ruled during a period of economic decline, and Medici control of Florence ended in 1737. One of the final acts of the last grand duke, Gian Gastone, was to memorialize Galileo in Florences Basilica di Santa Croce, sometimes called the Temple of the Italian Glories for the notable figures buried there.