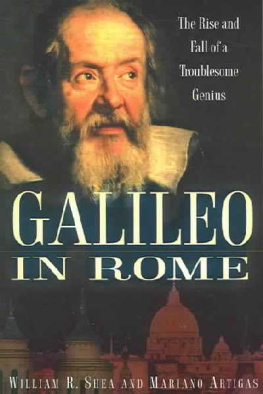

Galileo in Rome

Oxford New York

Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai

Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi

So Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto

Copyright 2003 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

First published by Oxford University Press, Inc., 2003

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 2004

ISBN 978-0-19-517758-9

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,

or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording,

or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

The Library of Congress has catalogued the cloth edition as follows:

Artigas, Mariano.

Galileo in Rome : the rise and fall of a troublesome genius / Mariano

Artigas and William R. Shea.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Galilei, Galileo, 1564-1642JourneysItalyRome.

2. Religion and scienceHistory16th century.

3. AstronomersItalyBiography.

I. Shea, William R.

II. Title.

QB36.G2 A69 2003

52092dc21 2003004247

Book design by planettheo.com

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

Job Hunting and the Path to Rome

FIRST TRIP: 1587

CHAPTER TWO

The Door of Fame Springs Open

SECOND TRIP: 29 MARCH-4 JUNE 1611

CHAPTER THREE

Roman Clouds

THIRD TRIP: 10 DECEMBER 1615-4 JUNE 1616

CHAPTER FOUR

Roman Sunshine

FOURTH TRIP: 23 APRIL-16 JUNE 1624

CHAPTER FIVE

Star-Crossed Heavens

FIFTH TRIP: 3 MAY-26 JUNE 1630

CHAPTER SIX

Foul Weather in Rome

SIXTH TRIP: 13 FEBRUARY-6 JULY 1633

We wish to thank most warmly the Templeton Foundation for providing us with a grant to coordinate our work and carry out research in the archives in Rome and Florence. We are also grateful to Paolo Galluzzi and his staff at the Institute and Museum of the History of Science in Florence, to Monsignor Alejandro Cifres, who has made the Archives of the Holy Office in the Vatican a friendly place to work, and to the officials of the Vatican Library, the Biblioteca di Archeologia e Storia dellArte and the Biblioteca Vallinceliana in Rome. We owe special thanks to Lucia Caravale of the Societ Dante Alighieri in Rome for making available documents regarding the Palazzo Firenze, where Galileo spent a great part of his time in Rome, and to several others whom we are pleased to mention here: Corrado Calisi of the Biblioteca della Camera dei Deputati, who introduced us to the Galileo Rooms that were formerly part of the convent of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, where Galileo was tried; Irene Trevor of the American Academy in Rome, who graciously allowed us to visit the Casa Rustica, where Cesis dinner in honour of Galileo took place in 1611; Cosimo di Fazio, who provided information on the Florentine residences of Galileo and enabled us to visit the Convent of San Mateo in Arcetri; Mario Sirignano, of the Accademia dei Lincei who taught us to walk in Galileos footsteps in Rome; the librarians of the Biblioteca Nazionale and of the Archivio di Stato in Florence; Rafael Martinez of the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross in Rome, who undertook a detailed study of a manuscript on Galileo that contains novel and exciting material that one of us (Mariano) came across in the Archives of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in the Vatican (formerly the Holy Office). Special thanks to Eugenio Calimani, the Dean of the Faculty of Science of the University of Padua, for providing a friendly and stimulating environment in which to complete our book.

Galileo is the father of modern science and a major figure in the history of mankind. He belongs to the small group of thinkers who transformed Western culture, and his clash with ecclesiastical authorities is one of the most dramatic incidents in the long history of the relations between science and religion.

In 1633 the Roman Inquisition condemned Galileo for teaching that the earth moves. The trial was the outcome of a series of events that are described in this book and are usually referred to as the Galileo Affair. It extended over a period of several years, during which different popes, cardinals, and civil personalities entered the scene and made their exit. We can even speak of two Galileo trials, one in 1616 and the other in 1633, although only the second was a trial in the legal sense. The new science, which today pervades our entire life, was just emerging, and very few were able to realize what was happening at the time. Most people were not ready to abandon cherished traditional ideas for daring hypotheses that had yet to be proved.

Galileo made six long visits to Rome, totaling over five hundred days, during which he met the pope, high-ranking members of the Church and the nobility, as well as leading figures of the literary and scientific establishment. His career can be seen in a novel and fascinating way when studied from the vantage point of the city where he was most anxious to be known and approved. This is what our work does for the first time. Each chapter corresponds to one trip, thereby providing a clear framework for the main events of Galileos life and allowing a fresh insight into the nature of the problems that he faced.

Galileo was deeply influenced by his close contacts with members of the ecclesiastical and the scientific community in Rome and, as time went on, he changed his agenda to fit new circumstances. He sometimes met with success, but he ultimately overplayed his hand and the outcome was dramatic. On the short term, his strategy was a failure; on the long term, he clearly emerged the winner.

The six trips occurred over a period of 46 years. The first took place in 1587, when Galileo, then 23 years old, went to Rome to meet scientists who might help him obtain a university appointment. With the assistance of Christopher Clavius, a Roman Jesuit professor, he got his first job at the University of Pisa in 1589 and, in 1592, he moved to the University of Padua, where he spent the next 18 years. After the publication of his astronomical discoveries had transformed him into a celebrity, Galileo returned to Florence, where he became the mathematician and philosopher of the grand duke of Tuscany. The next year, in 1611, he undertook a second and triumphal trip to Rome. He was made welcome by top-level members of the Church and the teaching profession. Unfortunately, his celebrity also gave rise to jealousy and opposition, especially when he began defending in public the Copernican view that the Earth is in motion and revolves around the Sun. This went against the commonsensical view that the Earth (and therefore humanity) is at the center of the universe, a belief that current scientific shared with tradition and Christian doctrine.

The opposition first arose among Aristotelian professors, but they soon managed to involve clerics who did not relish having to reinterpret Scripture in the light of new ideas. Galileo found out that he had been denounced to the Holy Office, and he traveled to Rome for the third time in December 1615 in order defend himself and avoid the condemnation of the heliocentric theory. He was brilliant in discussion, but to no avail. Copernicuss book on the motion of the Earth was banned in 1616, and Galileo was admonished not to teach it. He returned to Florence and was silent on the matter until his friend and admirer Maffeo Barberini was elected pope in 1623, taking the name of Urban VIII. A year later Galileo made his fourth trip to Rome, where he was received six times by the pope. This trip was another triumph, and Galileo felt he could now publish his ideas as long as they were presented as conjectures. This is how his celebrated