GALILEO GALILEI

The Essential Galileo

GALILEO GALILEI

The Essential Galileo

Edited and Translated by

Maurice A. Finocchiaro

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Indianapolis/Cambridge

Copyright 2008 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

For further information, please address

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

P.O. Box 44937

Indianapolis, Indiana 46244-0937

www.hackettpublishing.com

Cover design by Brian Rak and Abigail Coyle

Interior design by Elizabeth L. Wilson

Composition by Professional Book Compositors, Inc.

Printed at Edwards Brothers, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Galilei, Galileo, 15641642.

[Selections. English. 2008]

The essential Galileo / Galileo Galilei ; edited and translated by

Maurice A. Finocchiaro.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87220-937-4 (pbk.) ISBN 978-0-87220-938-1 (cloth)

1. ScienceEarly works to 1800. 2. AstronomyEarly works to 1800.

3. ScienceHistory. 4. Galilei, Galileo, 15641642. 5. Scientists

Italy. I. Finocchiaro, Maurice A., 1942 II. Title.

Q155.G27 2008

500dc22 2008018659

ePub ISBN: 978-1-60384-258-7

Contents

This is a collection of Galileos most important writings, covering his entire career. Here the relevant concept of importance centers on their historical impact, and the history in question includes not only Galileos life and the 17th century, but also the historical aftermath up to our own day. Moreover, the relevant historical impact is interdisciplinary in the sense that it affects the history of science (especially physics and astronomy), the philosophy of science (especially epistemology and scientific methodology), and general culture (especially the relationship between science and the Catholic Church, or more broadly science and religion).

In making the selections by applying such a criterion of importance, I consulted a number of scholars who provided valuable suggestions that reflected this and additional noteworthy criteria. Their names will be acknowledged below, and I hope they will easily see that I adopted many of their suggestions. I could not adopt literally all of their good suggestions, simply for lack of space. In fact, an important guiding principle has been that the resulting volume should be relatively small and inexpensive, in accordance with a time-tested formula provided by the publisher.

The translations are based on the text found in the National Edition of Galileos collected works (Galilei 18901909). To facilitate references, the page numbers of that edition are reproduced here by placing the corresponding numerals in square brackets in the text. Similarly, I have added section numbers preceded by the section sign (), in order to keep track of the various selections, to provide a more convenient means of cross-referencing, and to give to the text some structure that may serve as a guide for discussion. Additionally, section titles have been added, except within the two works that are included in their entirety (The Sidereal Messenger and the Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina), in which only section numbers are provided. Such section numbers and titles are bracketed when referring to passages from longer Galilean works, but they are not when referring to letters, trial documents, and self-contained essays.

For some of the translations I have revised works that are in the public domain. Others are taken from my own previously published translations. And a few have been newly made for this volume.

In particular, for The Sidereal Messenger (), I have revised the translation first published by Henry Crew and Alfonso De Salvio in 1914. With rare exceptions indicated in the notes, my revisions are usually made without comment. In this I was guided by the desire to improve accuracy and readability. For these Galilean works, it would have been ideal to reprint (with or without revisions) the excellent translations published, respectively, by Albert Van Helden (1989) and by Drake (1981) and (1974). However, copyright considerations made this ideal unfeasible. On the other hand, a beneficial byproduct of this practical necessity has been that the translations in this volume have greater linguistic and stylistic uniformity than they would otherwise have.

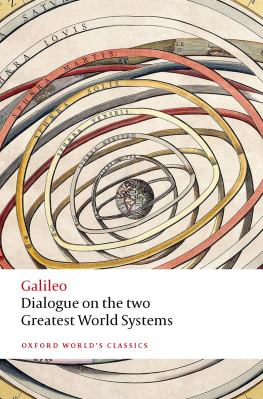

For the selections from Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems, Ptolemaic and Copernican (). Such reprintings are almost completely verbatim, but they do contain a few corrections, which have been indicated in the notes.

The new translations are the selections from the History and Demonstrations Concerning Sunspots ().

Needless to say, in all these cases, I have consulted and benefited from the translations already available in multiple languages, especially the following: for The Sidereal Messenger, the translations by Van Helden (1989), Lanzillotta (in Galilei 1953), Drake (1983), Pantin (1992), and Maria Timpanaro Cardini (in Galilei 1993); for the Discourse on Bodies in Water, the translation by Drake (1981); for the History and Demonstrations Concerning Sunspots, the translations by Drake (1957) and Reeves and Van Helden (forthcoming); for , which come from my previously published books, the translations acknowledged in the prefaces to those works; for The Assayer, the translations by Arthur Danto (in Galilei 1954) and Drake and OMalley (1960); and for the Two New Sciences, the translations by Drake (1974) and Adriano Carugo and Ludovico Geymonat (in Galilei 1958).

The notes, with very few exceptions, have been compiled especially for this volume, even when I was revising or reprinting previous translations. The reason is that some of those sources have too few annotations and some too many, and that in any case the notes had to be adopted for the present purpose. Thus, for example, since almost all terms and names requiring explanation occur in more than one selection, they are not explained in the notes but in the Glossary. A term or name is deemed as not requiring explanation when it is sufficiently explained or identified in the context of its occurrence (e.g., Lorinis name), or when it is commonly known or easily found in a small desk-dictionary (e.g., Archimedes, Aristotle, Copernicus, Euclid, Plato, Ptolemy, etc.). The few terms and names that occur only once (and that require explanation) are explained in notes at those places.

Finally, I would like to express thanks and acknowledgments to a number of people and institutions that helped in the creation of this book. Many scholars provided suggestions and encouragement: Mario Biagioli, Michele Camerota, Albert DiCanzio, Matthias Dorn, Paula Findlen, Owen Gingerich, Franco Giudice, Andr Goddu, W. Roy Laird, Ernan McMullin, David Miller, Ron Naylor, Margaret Osler, Paolo Palmieri, Michael Segre, Michael Shank, Robert Westman, and K. Brad Wray. The University of California Press granted me permission to reprint parts of my Galileo Affair and Galileo on the World Systems. The University of Nevada, Las Vegas, its Department of Philosophy, and my departmental colleagues have continued to provide institutional and moral support. And I thank Brian Rak, Editor at Hackett Publishing Company, for his initial and constant encouragement and for his continued patience.

Galileos Legacy

[0.1] Galileo Galilei was one of the founders of modern science. That is, science as we know it today emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries thanks to the discoveries, inventions, ideas, and activities of a group of people like Galileo that also included Nicolaus Copernicus, Johannes Kepler, Ren Descartes, Christiaan Huygens, and Isaac Newton. Frequently Galileo is singled out as the most pivotal of these founders and called the Father of Modern Science. Although many people have repeated or elaborated such a characterization, it is important that it originates in the judgment of practicing scientists themselves, such as Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking. Thus, scientists and other educated persons ought to know something about Galileos scientific achievements. One of the aims of this book is to make available in a single volume those Galilean writings that contain his most important contributions to physics and astronomy, for example: the law of inertia, and the laws of falling bodies, of the pendulum, and of projectile motion; the telescope; the mountains on the moon, the satellites of Jupiter, the phases of Venus, and sunspots; and the confirmation of the Copernican theory of the earths motion.

Next page