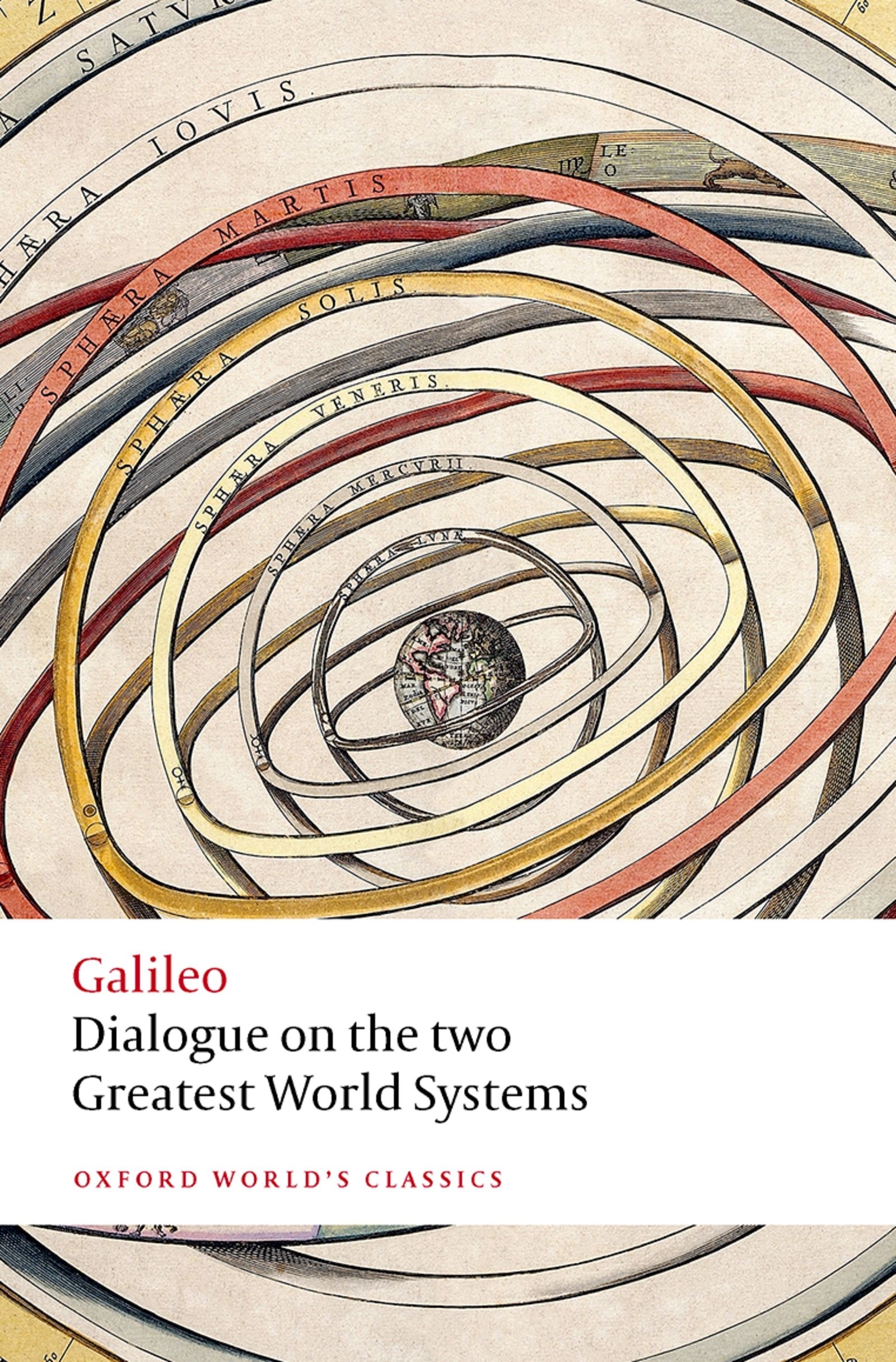

Galileo Galilei (15641642) is one of the most fascinating and controversial figures in the history of science. He was appointed professor of mathematics at the University of Pisa in 1589, and in 1592 he moved to the University of Padua where he taught for the next eighteen years. In 1610 he published a number of sensational telescopic discoveries, including that the lunar landscape is like that of a barren earth, and his book, the Sidereal Message, sold out in less than a week. The next year he was awarded the prestigious position of personal mathematician and philosopher to the Grand Duke of Tuscany in Florence. He next found that there are dark spots on the face of the sun and that gave rise to a lively international controversy that is recorded in his Letters on the Sunspots. He argued for a non-literal interpretation of the Bible, and he became involved in a dispute over the nature of comets with a Jesuit professor whom he lampooned in a witty essay, The Assayer. When the Roman Inquisition banned the Copernican theory in 1616, he refrained from writing about the motion of the Earth until a Florentine friend became Pope Urban VIII in 1623. His Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems, which is not only a scientific masterpiece but an outstanding literary work, appeared in 1632. Summoned to Rome he was put on trial and condemned to house arrest in 1633. He nonetheless went on to write his Discourse on Two New Sciences, the work for which he is remembered as the forerunner of Newton. He died in Florence in 1642.

William R. Shea was Galileo Professor of History of Science at the University of Padua where Galileo taught for eighteen years. He has written extensively on the Scientific Revolution of the seventeenth century, and is currently working on a biography of Galileo.

Mark Davie has taught Italian at the Universities of Liverpool and Exeter, and has published studies on various aspects of Italian literature, mainly in the period from Dante to the Renaissance. He is particularly interested in the relations between learned and popular culture, and between Latin and the vernacular, in Italy in the Renaissance.

Oxford Worlds Classics

For over 100 years Oxford Worlds Classics have brought readers closer to the worlds great literature. Now with over 700 titlesfrom the 4,000-year-old myths of Mesopotamia to the twentieth centurys greatest novelsthe series makes available lesser-known as well as celebrated writing.

The pocket-sized hardbacks of the early years contained introductions by Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot, Graham Greene, and other literary figures which enriched the experience of reading. Today the series is recognized for its fine scholarship and reliability in texts that span world literature, drama and poetry, religion, philosophy, and politics. Each edition includes perceptive commentary and essential background information to meet the changing needs of readers.

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox 2 6 dp , United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Editorial material William R. Shea 2022

Translation Mark Davie 2022

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

First published as an Oxford Worlds Classics paperback 2022

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022935975

ISBN 9780198840138

ebook ISBN 9780192576453

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Acknowledgements

Our debts to colleagues and friends are too numerous to be recorded in full but we wish to express our special gratitude to Michele Camerota, who supplied us with illuminating information on science in Galileos day, to Maurice A. Finocchiaro for helping us understand the clash between Galileo and the Church, and to Stefano Gattei for his scholarly study of Galileos background. We owe a special thanks to John Heilbron for his outstanding biography of Galileo and for his helpful advice. We are grateful to Flavia Marcacci for a better understanding of the history of Copernicanism, to Jrgen Renn for pointing out to us some of Galileos forerunners, to Gheorghe Stratan for his lucid critical advice, and to Gino Tarozzi who provided us with new insights.

We are deeply grateful to our wives, Evelyn and Grace, who have been admirably supportive and patient at all times, and to whom we owe more than one good idea.

Contents

Galileo Galilei was born in Pisa on 16 February 1564, the eldest son of Vincenzio Galilei and Giulia Ammannati. His father was a musician and the author of an influential Dialogue on Ancient and Modern Music that contains a fierce attack on his former master, Gioseffo Zarlino, and shows a gift for polemics that his son was to display in his own writings. The Galilei were an old Florentine family, and Galileos great-great-granduncle, also named Galileo Galilei, was a famous physician who had been twice elected officer of the Governing Body of Florence and, in 1445, filled the high office of Minister of Justice. Galileo was proud of his ancestry and he described himself as a noble Florentine on the title page of his first printed book, a handbook that appeared in 1606 on how to use a geometrical and military compass that he had invented.

Vincenzio Galileo had settled in Pisa when he married in 1562 but the family moved to Florence in 1574. In 1580 his son returned to Pisa to attend the University. At the time philosophy and science were still deeply influenced by the writings of the fourth-century bc Greek philosopher Aristotle, whose works were rediscovered in the Middle Ages. Aristotle maintained that things on Earth were made of four basic elements (earth, fire, air, and water) that were mixed in ever-changing proportions. He thought, however, that celestial bodies were made of an entirely different kind of material, which was unchangeable, or to use the old expression incorruptible. This physics was well adapted to the concept that the Earth is at rest, and it was seen as compatible with Christian theology. Young men studying for the priesthood were expected to grasp the main lines of Aristotelian cosmology. This did not hinder the development of observational astronomy or mathematics, to which the Jesuits, a religious teaching order founded in 1534, made significant contributions.