The Collected Works of

GALILEO GALILEI

(1564-1642)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2017

Version 1

The Collected Works of

GALILEO GALILEI

By Delphi Classics, 2017

With new introductions by

Professor Kenneth Richard Seddon, OBE

(QUILL, The Queens University of Belfast)

COPYRIGHT

Collected Works of Galileo Galilei

First published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2017.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 78656 058 2

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

Other classic Science and Philosophy eBooks available

These comprehensive editions are beautifully illustrated and offer eReaders some of the greatest scientific works ever written.

Explore Non-Fiction at Delphi Classics

The Books

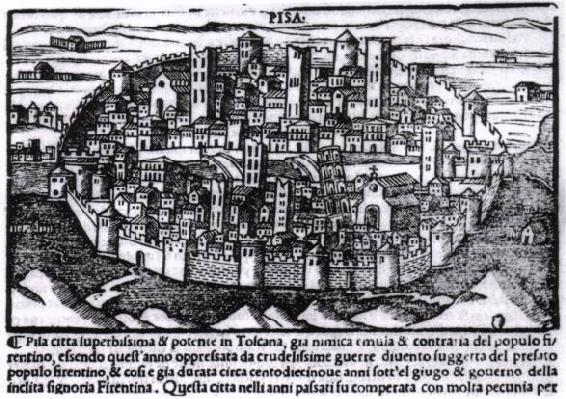

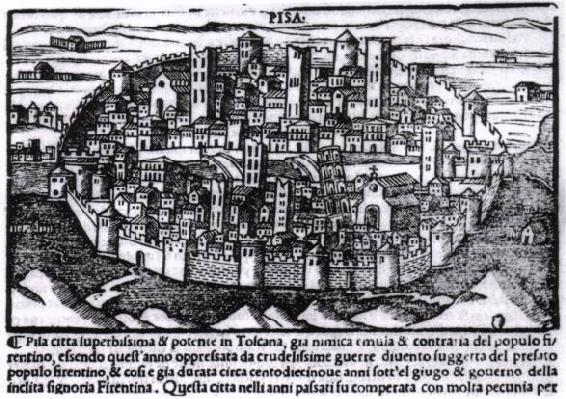

Pisa, Tuscany, central Italy Galileos birthplace

The birthplace of Galileo

Drawing of Pisa in the Renaissance, c. 1540

THE STARRY MESSENGER

Translated by Edward Stafford Carlos

The Oxford English Dictionary defines genius (noun) as the innate intellectual or creative power of an exceptional or exalted type, such as is attributed to those people considered greatest in any area of art, science, etc. ; instinctive and extraordinary capacity for imaginative creation, original thought, invention, or discovery. The modern media, with their love of superlatives, have devalued this term, but its original meaning remains unsullied in academic circles. There are few genii in our history, but perhaps the first that is universally recognised was Leonardo da Vinci (15 th April 1452 2 nd May 1519): a true genius and polymath scientist, artist, inventor - with footprints in almost all areas of academic endeavour including painting, sculpture, architecture, music, literature, science, mathematics, engineering, anatomy, geology, astronomy, botany, writing, history, and even map making. He was the archetype of Renaissance man. A century later, another genius was born in Italy - Galileo Galilei (15 th February 1564 8 th January 1642; see Figure 1) - astronomer, physicist, engineer, philosopher and mathematician. Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking two modern genii - credit him with being the progenitor of modern science, and his work had a profound influence on Sir Isaac Newton, laying the basis of his Laws of Motion, and later Einsteins Theory of Special Relativity.

Galileos first landmark book was published, in Latin, in 1610 (see Figure 2), revolutionising the science of astronomy. It was entitled Sidereus Nuncius : this is translated variously as Sidereal Messenger (see Figure 3), Starry Messenger , or Sidereal Message (the most accurate translation). It was the first astronomical book based on observations made with a telescope, and included studies of the moon, and of hundreds of previously unobserved stars. Galileo built his own telescope for this study, improving on the design available at the time. His observations of the moon (Figure 4) resulted in his deducing the existence of mountains and valleys on the lunar surface. His observations of the stars, especially the constellations of Orion (Figure 5) and the Pleiades (Figure 6) resulted in the number of observable stars being up to ten times the number previously observed. He also examined the Milky Way, and his comments, reproduced here, are both elegant and perceptive. I have observed the essence or substance of the MILKY WAY circle. By the aid of a telescope anyone may behold this in a manner which so distinctly appeals to the senses that all the disputes which have tormented philosophers through so many ages are exploded at once by the unquestionable evidence of our eyes, and we are freed from wordy disputes upon this subject, for the GALAXY is nothing else but a mass of innumerable stars planted together in clusters. Upon whatever part of it you direct the telescope straightway a vast crowd of stars presents itself to view; many of them are tolerably large and extremely bright, but the number of small ones is quite beyond determination.

Another key feature of this landmark volume is the discovery of the moons of Jupiter, which Galileo referred to as Medicean Stars, named for the four Medici brothers. He wrote: I therefore concluded, and decided unhesitatingly, that there are three stars in the heavens moving about Jupiter, as Venus and Mercury round the Sun; which at length was established as clear as daylight by numerous other subsequent observations. These observations also established that there are not only three, but four, erratic sidereal bodies performing their revolutions round Jupiter, observations of whose changes of position made with more exactness on succeeding nights. They are now known as Galilean moons, and named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto (all lovers of Zeus, or Jupiter) by Simon Marius (who independently discovered them a few days after Galileo).

And so the seeds were sown. Enlightened scientists, philosophers and artists greeted Sidereus Nuncius with acclaim. But many rejected the findings, ascribing them to lens defects in the telescope, and denied the existence of Jupiters moons. Independent verification of Galileos observations soon followed, confirming his conclusions that four moons orbited Jupiter.

Naming the moons after the Medici brothers moved the content of the book from scientific discourse to a political issue. Moreover, this book challenged the Churchs position the proof that the Milky Way consisted of a multitude of stars, and not the fiery exhalation of stars (the Aristotelian view), that Earths moon was not a perfect sphere, and his belief in the absolute truth of the Copernican heliocentric system (already downgraded to a hypothesis by the Church) were all seen to challenge scripture.

In the current post-truth (relating to, or denoting, circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief) era, we see a parallel for Galileos situation. In contradiction to the compelling weight of scientific evidence, in 1616 or 2016, it is possible to ignore or arbitrarily select data and arguments, and come to whatever conclusion you desire. Post-truth, then as now, is a weapon of ignorance and superstition, wielded by unscrupulous politicians and religious leaders. Whether it is a Church unwilling to accept a heliocentric system, creationists, or climate-change deniers, the same forces of ignorance and bigotry pervade public opinion.

Next page