The Collected Works of

NICCOL MACHIAVELLI

(1469-1527)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2017

Version 1

The Collected Works of

NICCOL MACHIAVELLI

By Delphi Classics, 2017

COPYRIGHT

Collected Works of Niccol Machiavelli

First published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2017.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 78656 065 0

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

Other classic Non-Fiction eBooks available

These comprehensive editions are beautifully illustrated, featuring rare works and offering eReaders some of the greatest non-fiction works ever written.

Explore Non-Fiction at Delphi Classics

The Political Works

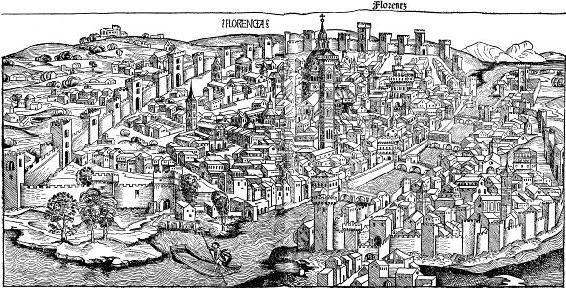

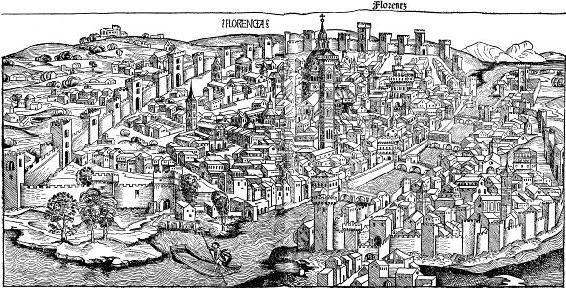

Florence, Tuscany Machiavelli was born in Florence, the third child of attorney Bernardo di Niccol Machiavelli and his wife, Bartolomea di Stefano Nelli. The Machiavelli family is believed to be descended from the old marquesses of Tuscany and to have produced thirteen Florentine Gonfalonieres of Justice.

View of Florence, c. 1490

Girolamo Savonarola being burnt at the stake in 1498 by an anonymous artist

THE PRINCE

This famous political treatise appears to have been distributed as early as 1513, when Machiavelli was forty-four years old, under the Latin title, De Principatibus (About Principalities). However, the printed version was not published until 1532, five years after Machiavellis death, with the permission of the Medici pope Clement VII. It was written in vernacular Italian rather than Latin, a practice that had become increasingly popular since the publication of Dantes Divine Comedy and other works of Renaissance literature. The Prince is regarded as the first work of modern political philosophy, in which the effective truth is taken to be more important than any abstract ideal. The treatise was also in direct conflict with the dominant Catholic and scholastic doctrines of the time concerning politics and ethics, causing much controversy.

Although it is a relatively short text, it is the most remembered of Machiavellis works and the one most responsible for bringing the word Machiavellian into usage as a pejorative term. The Prince even contributed to the modern negative connotations of the words politics and politician in western countries. In terms of subject matter, the treatise overlaps with Machiavellis much longer Discourses on Livy , composed a few years later.

The Prince opens with an explanation of the subject matter it will concern, analysing all forms of organisation of supreme political power, whether republican or princely. Machiavelli deals with hereditary princedoms promptly in Chapter 2, claiming that they are much easier to rule. For such a prince, unless extraordinary vices cause him to be hated, it is reasonable to expect that his subjects will be naturally well disposed towards him. Machiavelli divides the subject of new states into two types, mixed cases and purely new states. He argues that new princedoms are either entirely new, or they are mixed, as they are new parts of an older state already belonging to that prince. He generalises that there were several virtuous Roman ways to hold a newly acquired province, using a republic as an example of how new princes can act:

- to install ones princedom in the new acquisition, or to install colonies of ones people there, which is better.

- to indulge the lesser powers of the area without increasing their power.

- to put down the powerful people.

- not to allow a foreign power to gain reputation.

More generally, Machiavelli emphasises that one should have regard not only for present problems, but also for future difficulties. One should not enjoy the benefit of time, but rather the benefit of ones virtue and prudence, as time can bring evil as well as good.

In the fifth chapter, Machiavelli explains that when the kingdom revolves around the king, then it is difficult to enter, but easy to hold. The solution is to eliminate the old bloodline of the prince. Machiavelli uses the Persian empire of Darius III, conquered by Alexander the Great, to illustrate this point and then notes that the Medici, if they would consider it, will find this historical example similar to the kingdom of the Turk (Ottoman Empire) in their time making this a potentially easier conquest to hold than France would be.

As shown by his letter of dedication, The Prince eventually came to be dedicated to Lorenzo di Piero de Medici, grandson of Lorenzo the Magnificent and a member of the ruling Florentine Medici family, whose uncle Giovanni became Pope Leo X in 1513. It is known from his personal correspondence that the treatise was written during 1513, the year after the Medici took control of Florence and a few months after Machiavellis arrest, torture and banishment by the new Medici regime. The text was discussed for a long time with Francesco Vettori a friend of Machiavelli whom he wanted to approve the book and commend it to the Medici. It had originally been intended for Giuliano di Lorenzo de Medici, young Lorenzos uncle, who however died in 1516. It is not certain that the work was ever read by any of the Medici before it was printed. Machiavelli describes the contents as being an unembellished summary of his knowledge about the nature of princes and the actions of great men, based not only on reading but also on real experience.

The types of political behaviour which are discussed with apparent approval by Machiavelli in the treatise were regarded as shocking by contemporaries and its immorality remains to this day a subject of serious discussion. Although it advises princes how to tyrannise, Machiavelli is generally thought to have preferred a form of free republic. Some commentators justify his acceptance of immoral and criminal actions of leaders by arguing that he lived during a time of continuous political conflict and instability in Italy and that his influence has increased the pleasures, equality and freedom of many people, loosening the grip of medieval Catholicisms classical teleology, which disregarded not only the needs of individuals and the wants of the common man, but stifled innovation, enterprise, and enquiry into cause and effect relationships that now allow us to control nature.

Next page