The Collected Works of

THEOPHRASTUS

(c. 371 c. 287 BC)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2019

Version 1

Browse Ancient Classics

The Collected Works of

THEOPHRASTUS

By Delphi Classics, 2019

COPYRIGHT

Collected Works of Theophrastus

First published in the United Kingdom in 2019 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2019.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 78877 988 3

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

The Translations

Eresos, a village in Lesbos, Greece Theophrastus birthplace

Enquiry into Plants

Translated by Arthur F. Hort

Theophrastus Enquiry into Plants is one of the most important books of natural history written in ancient times, which would be an influential work in the Renaissance. The text examines in detail plant structure, reproduction and growth, as well as describing the varieties of plants around the world and their various uses. Book 9, is of particular note, detailing the medicinal uses of plants, offering advice on how to gather and apply them.

Enquiry into Plants was written between c. 350 and c. 287 BC in ten volumes, of which nine survive. The text attempts to construct a biological classification based on how plants reproduce a first in the history of botany. Theophrastus continually revised the manuscript and so it remained in an unfinished state on his death. The condensed style of the text, with its many lists of examples, indicates that Theophrastus used the manuscript as the working notes for lectures to his students, rather than intending it to be read as a unified work. It is believed that Theophrastus made use of a variety of sources for Enquiry into Plants , including Diocles work on drugs and medicinal plants. In the text, Theophrastus also claims to have gathered information from drug-sellers and root-cutters.

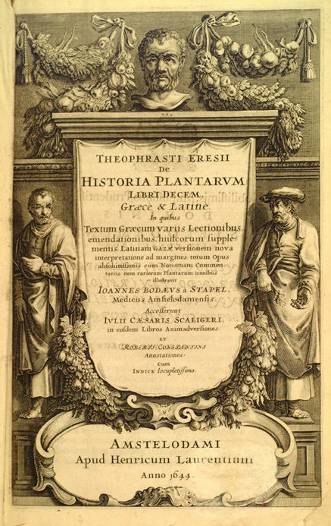

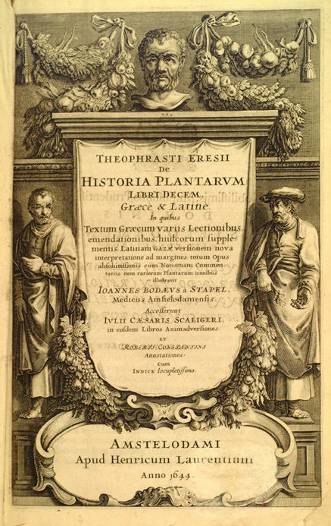

The treatise was first translated into Latin by Theodore Gaza in 1483. Johannes Bodaeus published a frequently cited folio edition in Amsterdam in 1644, complete with commentaries and woodcut illustrations. The first English translation was made by Sir Arthur Hort for the Loeb Classical Series, which was published in 1916.

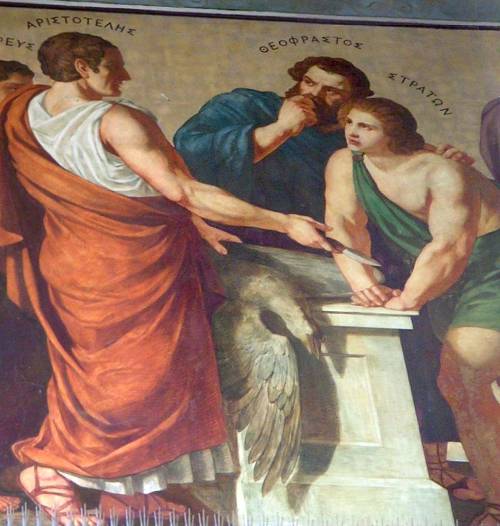

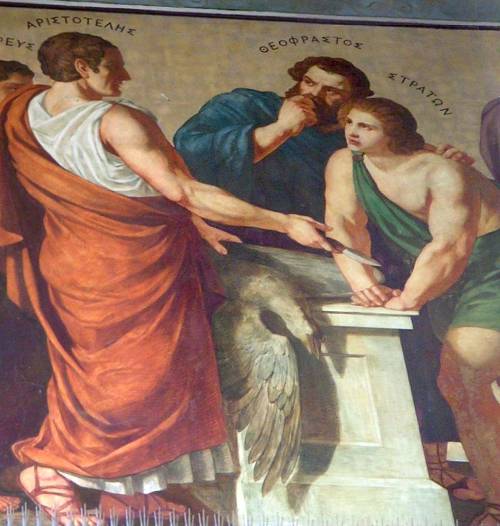

Aristotle, Theophrastus, and Strato of Lampsacus. Part of a fresco in the portico of the University of Athens painted by Carl Rahl, c. 1888

CONTENTS

Frontispiece to the illustrated 1644 edition of Enquiry into Plants

BOOK I. OF THE PARTS OF PLANTS AND THEIR COMPOSITION.

[1.1] In considering the distinctive characters of plants and their nature generally one must take into account their parts, their qualities, the ways in which their life originates, and the course which it follows in each case: (conduct and activities we do not find in them, as we do in animals). Now the differences in the way in which their life originates, in their qualities and in their life-history are comparatively easy to observe and are simpler, while those shewn in their parts present more complexity. Indeed it has not even been satisfactorily determined what ought and what ought not to be called parts, and some difficulty is involved in making the distinction.

[1.2] Now it appears that by a part, seeing that it is something which belongs to the plants characteristic nature, we mean something which is permanent either absolutely or when once it has appeared (like those parts of animals which remain for a time undeveloped) permanent, that is, unless it be lost by disease, age or mutilation. However some of the parts of plants are such that their existence is limited to a year, for instance, flower, catkin,leaf, fruit, in fact all those parts which are antecedent to the fruit or else appear along with it. Also the new shoot itself must be included with these; for trees always make fresh growth every year alike in the parts above ground and in those which pertain to the roots. So that if one sets these down as parts,the number of parts will be indeterminate and constantly changing; if on the other hand these are not to be called parts, the result will be that things which are essential if the plant is to reach its perfection, and which are its conspicuous features, are nevertheless not parts; for any plant always appears to be, as indeed it is, more comely and more perfect when it makes new growth, blooms, and bears fruit. Such, we may say, are the difficulties involved in defining a part.

[1.3] But perhaps we should not expect to find in plants a complete correspondence with animals in regard to those things which concern reproduction any more than in other respects; and so we should reckon as parts even those things to which the plant gives birth, for instance their fruits, although we do not so reckon the unborn young of animals. (However, if such a product seems fairest to the eye, because the plant is then in its prime, we can draw no inference from this in support of our argument, since even among animals those that are with young are at their best.)

Next page