The Complete Works of

ARISTOXENUS OF TARENTUM

(fl. 4 th century BC)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2021

Version 1

Browse Ancient Classics

The Complete Works of

ARISTOXENUS OF TARENTUM

By Delphi Classics, 2021

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Aristoxenus

First published in the United Kingdom in 2021 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2021.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 9781801700115

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

The Translation

Taranto, ancient site of Tarentum, a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy Aristoxenus birthplace

Ancient ruins in the Temple of Poseidon, Taranto

The Elements of Harmony

Translated by Henry Stewart Macran, 1902

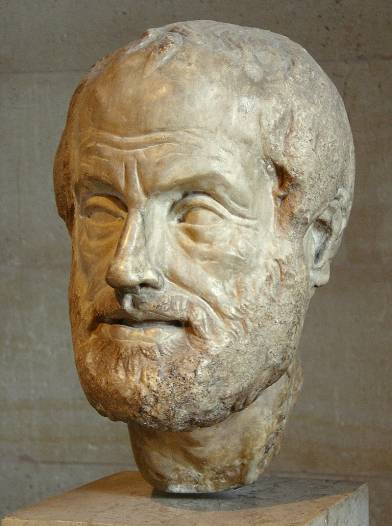

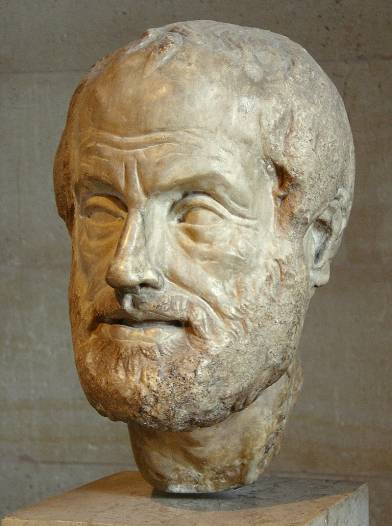

Flourishing in the fourth century BC, Aristoxenus of Tarentum was a Greek Peripatetic philosopher and a pupil of Aristotle. Almost all of his writings, consisting of four hundred and fifty-three books, dealing with philosophy, ethics and music, have been lost. Only a treatise on music, Elements of Harmony ( ) survives in a significant state, though the text is incomplete. The book is of invaluable worth, providing the chief source of knowledge on ancient Greek music.

Aristoxenus was born at Tarentum, the son of a learned musician named Spintharus (otherwise Mnesias). He was instructed by Lamprus of Erythrae and Xenophilus the Pythagorean, before finally becoming a pupil of Aristotle, whom he appears to have rivalled in the variety of his studies. According to the Suda, Aristoxenus heaped insults on Aristotle after his death, when Theophrastus was named the next head of the Peripatetic school, which position Aristoxenus had coveted after achieving great distinction. Nonetheless, the story is contradicted by the Peripatetic philosopher Aristocles of Messene (fl. 2nd century), who asserts that Aristoxenus only ever mentioned Aristotle with the greatest respect. Nothing is known of Aristoxenus life after the time of Aristotles departure, save for the comments he makes in Elements of Harmony . Aristoxenus was strongly influenced by Pythagoreanism, having grown up in the profoundly Pythagorean city of Tarentum, home also of the two Pythagoreans Archytas and Philolaus.

In Elements of Harmony Aristoxenus presents a complete and systematic exposition of music. It helped launch a tradition of the study of music based on practice, understanding music by study to the ear. Musicology as a discipline achieved nascency with the systematic study undertaken in Aristoxenus landmark work, which treats music independently of prior studies that held it in a position of something purely and only in relation to an understanding of the kosmos. Aristoxenus study of harmonics is especially concerned with treating melody () in order to find its components.

In the first sentence of the treatise, Aristoxenus identifies Harmony as belonging under the general scope of the study of the science of Melody. He considers notes to fall along a continuum available to auditory perception, identifying the three tetrachords as diatonic, the chromatic and the enharmonic. The first book provides an explanation of the genera of Greek music and also of their species. This is followed by several general definitions of terms, particularly those of sound, interval and system. In the second book Aristoxenus divides music into seven parts: the genera, intervals, sounds, systems, tones or modes, mutations and melopoeia. The remainder of the treatise is taken up with a discussion of the many parts of music according to the order that Aristoxenus has prescribed. He makes extensive use of arithmetic terminology, notably to define varieties of semitones and dieses in the descriptions of the various genera.

In his second book, the author asserts that by the hearing we judge of the magnitude of an interval, and by the understanding we consider its many powers. He later expands, that the nature of melody is best discovered by the perception of sense and is retained by memory; and that there is no other way of arriving at the knowledge of music.

In the third and final book, Aristoxenus describes twenty eight laws of melodic succession, which are of great interest to those concerned with classical Greek melodic structure.

Portrait bust of Aristotle; an Imperial Roman copy (c. second century AD) of a lost bronze sculpture made by Lysippos

CONTENTS

The Cylix of Apollo with the tortoise-shell lyre, on a fifth century BC drinking cup (kylix)

BOOK I

[The references throughout the translation are to Meiboms edition.]

[1] THE branch of study which bears the name of Harmonic is to be regarded as one of the several divisions or special sciences embraced by the general science that concerns itself with Melody. Among these special sciences Harmonic occupies a primary and fundamental position; its subject matter consists of the fundamental principles all that relates to the theory of scales and keys; and this once mastered, our knowledge of the science fulfils every just requirement, because it is in such a mastery that its aim consists. In advancing to the profounder speculations [2] which confront us when scales and keys are enlisted in the service of poetry, we pass from the study under consideration to the all-embracing science of music, of which Harmonic is but one part among many. The possession of this greater science constitutes the musician.

Next page