The Complete Works of

ATHENAEUS

(fl. late 2 nd century AD)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2017

Version 1

The Complete Works of

ATHENAEUS OF NAUCRATIS

By Delphi Classics, 2017

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Athenaeus

First published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2017.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 78656 392 7

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

The Translation

Ruins at Siwa, near Naucratis, a city of Ancient Egypt, on the Canopic branch of the Nile, 45 miles southeast of Alexandria Athenaeus birthplace

THE DEIPNOSOPHISTAE

Translated by C. D. Yonge

A Greek rhetorician and grammarian of the late second century AD, Athenaeus of Naucratis lived in the times of Marcus Aurelius and Commodus, who died in 192. Although several of his books are lost, the fifteen-volume Deipnosophistae (dinner-table philosophers) mostly survives and belongs to the literary tradition inspired by the use of the symposium the Greek banquet. The first two books, and parts of the third, eleventh and fifteenth, are extant only in epitome. The text offers the interested reader an immense store-house of information, chiefly on matters connected with dining, but also containing remarks on music, songs, dances, games, courtesans and luxury. Nearly 800 writers and 2500 separate works are referred to by Athenaeus, preserving many rare fragments otherwise lost. Were it not for Athenaeus, much valuable information about the ancient world would be missing and many ancient Greek authors, such as Archestratus, would be almost entirely unknown.

The Deipnosophistae professes to be an account given by an individual named Athenaeus to his friend Timocrates of a banquet held at the house of Larensius, a wealthy book-collector and patron of the arts. Therefore, the text serves as a dialogue within a dialogue, in the manner of Plato, though the conversation extends to an enormous length. The twenty-four guests include individuals named Galen and Ulpian, but they are all probably fictitious personages and the majority take no part in the conversation.

The topics for discussion generally arise from the course of the dinner itself, but extend to literary and historical matters of every description, including abstruse points of grammar, while the guests supposedly quote from memory. The actual sources of the material preserved in the Deipnosophistae remain obscure, but much of it likely comes at second-hand from early scholars.

The complete version of the text, with the noted lacunae, is preserved in only one manuscript, conventionally referred to as A . The epitomised version of the text is preserved in two manuscripts, usually known as C and E . The encyclopaedist and author Sir Thomas Browne wrote a short essay upon Athenaeus, demonstrating a revived interest in the book amongst scholars during the seventeenth century, after its publication in 1612 by the Classical scholar Isaac Casaubon.

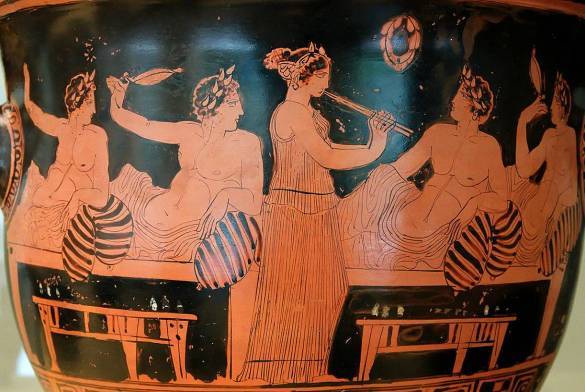

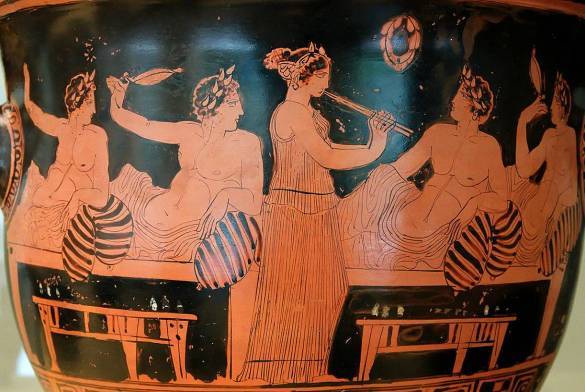

The following text belongs to the literary tradition inspired by the use of the Greek banquet. The ancient piece of pottery depicts several banqueters playing Kottabos while a musician plays the Aulos produced by the artist Nikias.

Bust of Marcus Aurelius (121-180 AD) in the Muse Saint-Raymond, Toulouse, France

CONTENTS

Commodus (161-192 AD) as Hercules, Capitoline Museums

PREFACE.

The author of the Deipnosophists was an Egyptian, born in Naucratis, a town on the left side of the Canopic Mouth of the Nile. The age in which he lived is somewhat uncertain, but his work, at least the latter portion of it, must have been written after the death of Ulpian the lawyer, which happened A. D. 228.

Athenus appears to have been imbued with a great love of learning, in the pursuit of which he indulged in the most extensive and multifarious reading; and the principal value of his work is, that by its copious quotations it preserves to us large fragments from the ancient poets, which would otherwise have perished. There are also one or two curious and interesting extracts in prose; such, for instance, as the account of the gigantic ship built by Ptolemus Philopator, extracted from a lost work of Callixenus of Rhodes.

The work commences, in imitation of Platos Phdo, with a dialogue, in which Athenus and Timocrates supply the place of Phdo and Echecrates. The former relates to his friend the conversation which passed at a banquet given at the house of Laurentius, a noble Roman, between some of the guests, the best known of whom are Galen and Ulpian.

The first two books, and portions of the third, eleventh, and fifteenth, exist only in an Epitome, of which both the date and author are unknown. It soon, however, became more common than the original work, and eventually in a great degree superseded it. Indeed Bentley has proved that the only knowledge which, in the time of Eustathius, existed of Athenus, was through its medium.

Athenus was also the author of a book entitled, On the Kings of Syria, of which no portion has come down to us.

The text which has been adopted in the present translation is that of Schweighuser.

C. D. Y.

BOOK I. EPITOME.

The Deipnosophists, or the Banquet of the Learned.

1. Athenus is the author of this book; and in it he is discoursing with Timocrates: and the name of the book is the Deipnosophists. In this work Laurentius is introduced, a Roman, a man of distinguished fortune, giving a banquet in his own house to men of the highest eminence for every kind of learning and accomplishment; and there is no sort of gentlemanly knowledge which he does not mention in the conversation which he attributes to them; for he has put down in his book, fish, and their uses, and the meaning of their names; and he has described divers kinds of vegetables, and animals of all sorts. He has introduced also men who have written histories, and poets, and, in short, clever men of all sorts; and he discusses musical instruments, and quotes ten thousand jokes: he talks of the different kinds of drinking cups, and of the riches of kings, and the size of ships, and numbers of other things which I cannot easily enumerate, and the day would fail me if I endeavoured to go through them separately.

Next page