The Complete Works of

PLOTINUS

(c.204270)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2015

Version 1

The Complete Works of

PLOTINUS

By Delphi Classics, 2015

COPYRIGHT

Complete Works of Plotinus

First published in the United Kingdom in 2015 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2015.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

The Translation

Ruins at Mendes, Egypt near Plotinus birthplace, Lycopolis, an ancient town in the Sebennytic nome in Lower Egypt, originally founded by a colony of Osirian priests.

ENNEADS

Translated by Stephen MacKenna

Plotinus Enneads is a collection of philosophical writings edited and compiled by his student Porphyry (c. 270 AD). Plotinus himself was a student of Ammonius Saccas and they are both now considered to be founders of Neoplatonism a modern term used to designate a tradition of philosophy that arose in the 3rd century AD and flourished until shortly after the closing of the Platonic Academy in Athens in AD 529. Neoplatonists were heavily influenced both by Plato and by the Platonic tradition that thrived during the six centuries that separated the first of the Neoplatonists from Plato. Plotinus work, through Augustine of Hippo, the Cappadocian Fathers, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and several subsequent Christian and Muslim thinkers, has greatly influenced the course of Western and Near-Eastern thought.

Porphyrys arrangement of the extant text does not follow the chronological order in which the Enneads were written, but instead responds to a plan of study, leading the learner from subjects related to his own affairs to subjects concerning the uttermost principles of the universe. Plotinus student organised the texts into fifty-four treatises, which vary greatly in length and number of chapters, mostly because he split original texts and joined others together to provide an exact number of fifty-four treatises in groups of nine ( ennea ) or Enneads . After correcting and naming each treatise, Porphyry wrote a biography of his master, which was intended to be an introduction to the collection.

Although not exclusively, the First Ennead concerns human and ethical topics, the Second and Third Enneads are mostly devoted to cosmological subjects or physical reality, the Fourth deals with matters of the Soul, the Fifth concerns knowledge and intelligible reality, whilst the Sixth and final Ennead covers Being and what is above it, as well as the One or first principle of all.

Plotinus writings teach the concept of a supreme, totally transcendent One, containing no division, multiplicity or distinction; beyond all categories of being and non-being. His One cannot be any existing thing, nor is it merely the sum of all things, but is prior to all existents. Plotinus identified his One with the concept of Good and the principle of Beauty. The One concept encompasses thinker and object. Even the self-contemplating intelligence (the noesis of the nous) must contain duality. Plotinus denies sentience, self-awareness or any other action ( ergon ) to the One. He argues that if we insist on describing it further, we must call the One a sheer potentiality ( dynamis ), without which nothing could exist.

Elsewhere in the Enneads , Plotinus offers an alternative to the orthodox Christian notion of creation ex nihilo (out of nothing), which attributes to God the deliberation of mind and action of a will, though he never refers to Christianity in any of his works. Emanation ex deo (out of God) confirms the absolute transcendence of the One, making the unfolding of the cosmos purely a consequence of its existence; the One is in no way affected or diminished by these emanations. To illustrate this, Plotinus uses the analogy of the Sun, which emanates light indiscriminately without thereby diminishing itself, or reflection in a mirror which in no way diminishes or otherwise alters the object being reflected.

Authentic human happiness for Plotinus consists of the true human identifying with that which is the best in the universe. As happiness is beyond anything physical, Plotinus stresses the point that worldly fortune does not control true human happiness, and thus there exists no single human being that possesses something we can truly regard as constituting happiness. The issue of happiness is one of Plotinus greatest imprints on Western thought, as he is one of the first to introduce the idea that eudaimonia (happiness) is attainable only within consciousness.

He goes on to argue that the true human is an incorporeal contemplative capacity of the soul and superior to all things corporeal. It then follows that real human happiness is independent of the physical world. Real happiness is, instead, dependent on the metaphysical and authentic human being found in this highest capacity of Reason. For man, and especially the Proficient, is not the Couplement of Soul and body: the proof is that man can be disengaged from the body and disdain its nominal goods. The human who has achieved happiness will not be bothered by sickness and discomfort, as his focus is on the greatest things. Authentic human happiness is the utilisation of the most authentically human capacity of contemplation. Even in daily, physical action, the flourishing humans act is determined by the higher phase of the soul. Plotinus summarises his claim of true happiness being metaphysical, by explaining how the truly happy human would understand that only a body is tortured, not the conscious self, and so happiness could subsist.

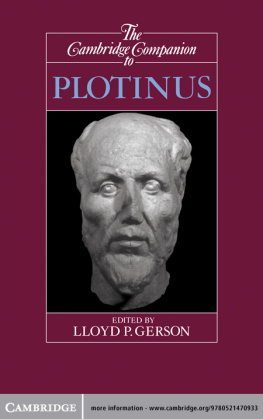

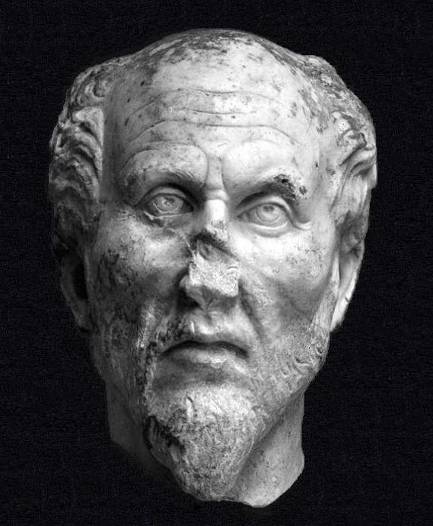

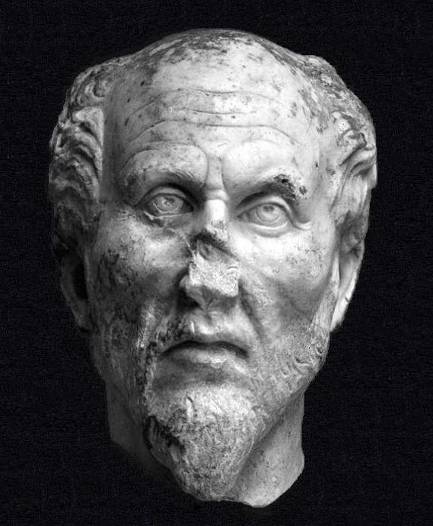

Head in white marble attrinuted to be a depiction of Plotinus, Ostia Antica

CONTENTS

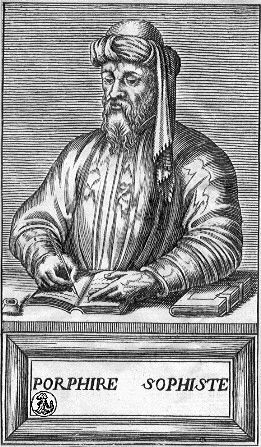

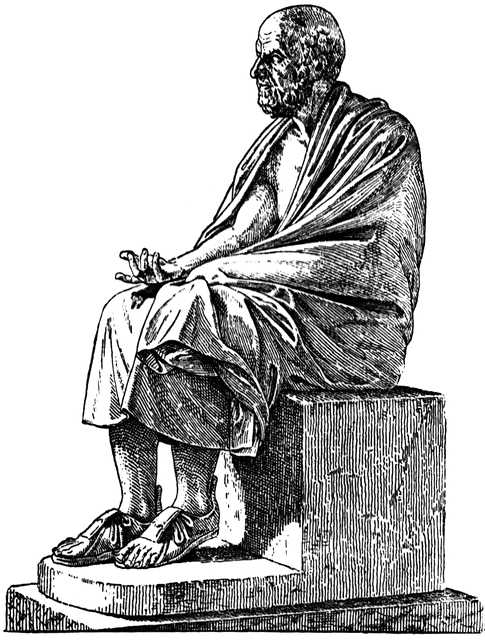

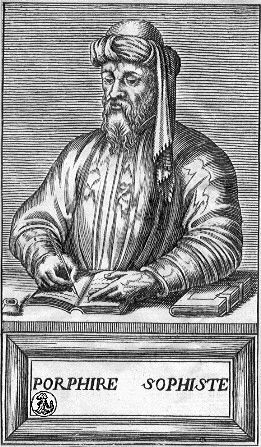

A sixteenth century engraving of Porphyry, Plotinus student

The First Ennead.

First Tractate.

The Animate and the Man.

1. Pleasure and distress, fear and courage, desire and aversion, where have these affections and experiences their seat?

Clearly, either in the Soul alone, or in the Soul as employing the body, or in some third entity deriving from both. And for this third entity, again, there are two possible modes: it might be either a blend or a distinct form due to the blending.

Next page